Mayor Eric Adams’ handpicked Charter Revision Commission on Thursday approved five proposals to go before New York City voters this November — a move that could give City Hall more power in the legislative process, while also blocking a City Council bill that would expand the chamber’s approval power over mayoral appointees.

The 13-member commission, comprised of the mayor’s close allies, advanced the five proposals to appear on the Nov. 5 general election ballot unanimously during its final meeting on July 25 at the Brooklyn Public Library’s Central Branch. The vote came after a rally outside the branch Thursday where City Council leaders blasted it as a “sham.”

Mayor Adams lauded the commission’s approval in a Thursday afternoon statement.

“This commission carefully examined our city’s Charter, heard from residents across all five boroughs, and approved thoughtful ballot proposals,” the mayor said. “New Yorkers will have the opportunity to vote on when they flip their ballots this November.”

The proposals resulted from 12 public hearings the commission held across each of the five boroughs over the past two months, which drew attendance from only 750 New Yorkers and a little over 2,000 pieces of in-person and virtual testimony. The Thursday meeting was also sparsely attended, and CRC Chair Carlo Scissura began the proceedings before security had even let all of the attendees into the room where it took place.

The commission released its final proposals earlier this week, not even 24 hours after its last public hearing in Queens. It then quietly amended its proposals minutes before the start of its Thursday meeting.

‘Do you want a king?’

For its part, the City Council argued that the panel “rushed” through its work by coming up with proposals in under two months, since it was convened in May, with input from a little over 2,000 New Yorkers in a city of 8.3 million people. Additionally, they charged that the commission’s real aim was to halt the its measure to expand their approval authority over mayoral appointments — a power known as “advice and consent.”

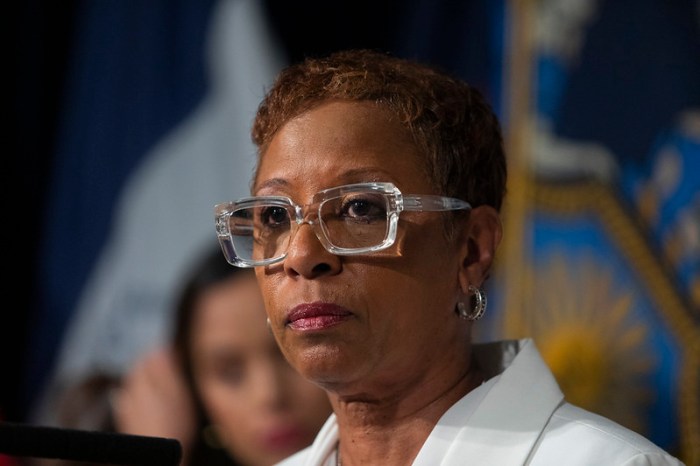

During the rally, City Council Speaker Adrienne Adams charged the mayor’s commission is not only a bid to block the council’s legislation, but that its proposals will take power away from the legislature and concentrate it in the executive branch.

“What is clear is that the mayor’s commission was created simply to block voters from deciding on the existing advice and consent proposal in this November’s election,” the speaker said. “It is a dangerous attempt to shift power away from the people represented by the City Council to one single individual. Do you want a king?”

Speaker Adams also said it was hypocritical for the commission to advance proposals around public notice of council legislation when the panel drafted proposals to change the City Charter in just nine weeks.

“The mayor’s Charter Revision Commission has rushed a far more extensive process, taking only nine weeks to review the entire city constitution and proposed changes to alter it for over 8 million people,” the speaker said. “This is the greatest show of hypocrisy, and it is an attack on our democracy.”

Council leaders were particularly incensed by two proposals that would give the mayor a larger hand in shaping legislation.

One would allow the mayor’s budget office to assess the fiscal impact of council bills before they are passed and the other would require advanced notice if the council intends to vote on bills impacting public safety.

The proposal surrounding the cost of legislation would mandate a cost assessment of a bill earlier in the lawmaking process, on top of one that is already required before it is voted on. Furthermore, it would let the mayor’s Office of Management and Budget conduct its own financial estimates on council bills at both points of the legislative process.

A slight change

However, minutes before the meeting began, the commission amended the public safety proposal, which would have required the body to give the administration a combined 90 days of prior notice in the process of passing legislation related to the NYPD, Fire Department and Department of Corrections. It would also allow the mayor and the agency impacted by the bill to hold public hearings on it during that period.

The amendment shortened that window to 30 days, which commissioners said was partially a response to council criticism.

“We have heard many comments from the public and others regarding this specific proposal,” Scissura said. “I have directed the staff to draft an amended proposal that would limit the requirements placed on the City Council, while retaining the mayors and commissioners’ ability to hold public hearings on critical public safety legislation, as is permitted currently by state law.”

The other three proposals passed by the commission are far less controversial.

One proposal expands and clarifies the city Department of Sanitation’s authority when it comes to cleaning city-owned property, requiring trash be placed in containers and enforcement of unlicensed street vendors in parks.

Another would update the city’s capital planning process by requiring more detailed assessments of city facilities’ maintenance needs; that a facility’s needs be taken into consideration; and updating deadlines for 10-year capital plans.

The last proposal would enshrine the chief business diversity officer position in the City Charter — making it the point of contact for Minority and Women-owned Business Enterprises, allow the mayor to authorize their Office of Media and Entertainment the power to issue film permits and combine two city boards that have overlapping missions of maintaining municipal archives.

A marginalized bill

But the charter commission’s vote effectively prevents the council’s advice-and-consent legislation from coming before voters this November, because state law gives proposals advanced by a mayoral charter commission priority for the ballot over those put forward by the legislature.

The council overwhelmingly passed the measure last month by a 46-to-4 vote and submitted it to the city Board of Elections for placement on the ballot last week. The bill expands the council’s power to approve mayoral appointments to an additional 20 city agencies; currently, it only has advice-and-consent for the heads of the Department of Investigation and Law Department.

While the mayor has not been shy about his opposition to expanding advice-and-consent, he has repeatedly denied that stopping it was the impetus for the commission. Instead, he says he convened the panel in response to a handful of advocates’ concerns that some council bills bear too large a price tag and that others are endangering public safety.

Adams declined to veto the bill earlier this month, anticipating that his downvote would get overridden by the council. He has also claimed to want to bury the hatchet with council leadership in recent weeks, following a flurry of high-profile spats between the two sides of City Hall over the past year and a half.

Yet council members, who were on the losing end of Thursday’s vote, did not seem as interested in letting bygones be bygones. They urged voters to reject the commission’s ballot questions in November, while vowing to fiercely campaign against the measures.

Brooklyn Council Member Shahana Hanif (D) said that while it will be complex telling voters to reject the five proposals — given that the November general election will have a high turnout in a year when the presidency is on the ballot — it is a challenge the council and advocates will take on.

“We’re looking forward to this coalition and working with our speaker and the entire council to ensure that we’re able to push back on this anti-democratic process,” she said.