Karlin Chan, who now trains lion dancers for Chinatown’s Lunar New Year parades, said when he performed in the ‘70s, it was a “free for all.”

BY SAM SPOKONY | With the Lunar New Year and its colorful costumes, pounding drums and exuberant lion dances starting this week, Chinatown’s cultural leaders are preparing for yet another celebration through the streets.

But even as the fanfare of those symbolic dances continues to evolve and grow in the 21st century, there are still those around town who remember a different time — one in which old-school tradition ruled the day, and proper practice of the most minute rituals meant the difference between public disgrace and hard-earned respect.

Longtime neighborhood advocate Karlin Chan fondly recalled those days as he sat within the 211 Canal St. headquarters of the New York Chinese Freemasons Athletic Club.

Chan, 56, is now the elder — essentially, the figurehead — of the Freemasons Club, which was established in 1956 and is Chinatown’s oldest surviving organization that still performs lion dancing on the New Year, along with other cultural events throughout the country.

“Back then, there wasn’t much for Chinese kids to do around here,” Chan said of the 1960s — the decade when he immigrated to New York from southern China with his parents at the age of 3. “All of us school kids would play with firecrackers, and after a while, we said, ‘Hey, let’s get involved with [the Freemasons Club],’ because they were in charge of the firecrackers during New Year’s celebrations.”

So he first joined the club in 1970, at age 12, as an “extra” — someone who held poles or flags alongside the performers. Over the next year, he studied under older mentors to become a lion dancer, first by learning the precise kung fu stances that were required of a trainee before he could even touch an actual lion “head” (the large, colorful apparatus used for the routines).

“At that time, I knew that if you wanted to get into lion dancing, your kung fu better be good,” he said, with a chuckle.

And so it had to be, because in the ‘70s the role of Chinatown’s dancers went much deeper than the Lunar New Year parade itself. The skills of organizations like the Freemasons Club were frequently tested by local shop owners — often those affiliated with rival kung fu schools — in elaborate public rituals.

Chan recalled one of those tests, in which a shop owner would place a head of lettuce, surrounded by a circle of seven tangerines, on the ground outside his door.

“And if you just walked up and grabbed the lettuce, people would laugh at you because they could tell you didn’t know what you were doing,” he said. Instead, the lion dancer — in full garb — would have to prove his skills by dancing around the arrangement of food several times, then circling back once and ceremonially “sniffing” the offering, and then accepting the tangerines one at time before finally snatching the lettuce.

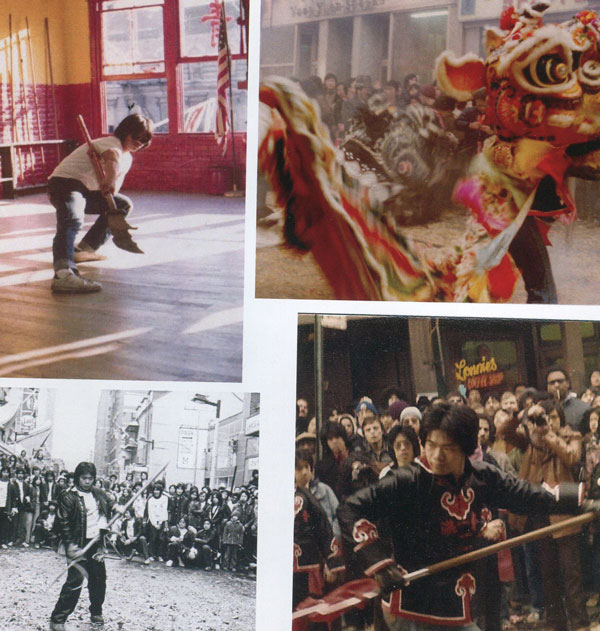

Karlin Chan as a lion dancer in the 1970s.

“These days, you don’t see that too much,” said Chan. “The tradition is still there, but a lot of those old customs are gone, or at least they’ve evolved.”

After undertaking his first actual lion dance at age 13, he went off into the rough and tumble world of New Year festivities — and several years later, he saw just how rough those rituals could get, in a time before the Police Department played an active role in overseeing the street parades.

“The city would just close down the streets around here for the New Year, and since every [dancing] group was on their own, it was basically a free for all,” he said of the ‘70s.

“And there were some fights,” he added.

Yes, in three consecutive years — 1973, 1974 and 1975 — street fights broke out among rival organizations during their celebratory parade routes through Chinatown. The reason? Again, tradition.

“If there are two different groups coming down the same street, they’re both supposed to bend down low with the lion head, as a sign of respect while passing each other,” said Chan. “And if one of the groups decides to raise their head, that’s a real public insult, because it basically means that they’re looking down on you.

“Back in the ‘70s, all the groups were really strutting their stuff, wanting to show off their school of kung fu,” he continued, “and at the slightest sign of disrespect, boom, that was it.”

Chan acknowledged that he and the Freemasons Club were in fact involved in one of those brawls, but didn’t want to go into specifics about that.

“Why bring up old wounds?” he said, with another laugh.

After those incidents, cops decided to take over and establish set routes that separated certain groups. Now, decades later, aside from the fact that the fire behind old Chinese rituals has certainly cooled off, the parade groups of each local organization are staffed by two police officers for general safety and street-crossing purposes.

“So you can’t get away with fighting now,” Chan noted, “although groups generally still observe the tradition of going low while passing one another.”

After those “glory days” of passion and punches on the street, he would go on to dance for another decade, recalling that his final appearance with a lion head took place in 1984 at a cultural convention in Baltimore. Now, Chan serves mainly as an advisory figure for the Freemasons Club, and works with local Chinatown organizations to promote the traditions he loves, while also overseeing the younger club members who train kids — now, he notes, of all races and ethnicities — who want to learn the art of lion dancing.

And besides its role as a showpiece for tourists these days, that dancing is, by the way, an act that’s symbolically meant to drive away evil spirits on the New Year. Historically, those fireworks that young Chan loved to play with served a complementary purpose on the holidays — by driving away demons.

Now that it’s not quite legal to shoot off fireworks in the street, that job of scaring demons is now accomplished — who knows how effectively? — by “party poppers” and other more innocuous noisemakers. Police do allow limited firecrackers in Sara D. Roosevelt Park, but Chan said he still misses the ones in the streets, even though he understands the importance of safety restrictions.

“I would just love to see the fireworks come back,” he said wistfully, “at least in some controlled way, because they really add to the celebration.”

One new effort that Chan is happy to see underway — since it’s also one that he’s already supported — is the push by Mayor Bill de Blasio, City Council Speaker Melissa Mark-Viverito and other elected officials to declare the Lunar New Year an official public school holiday for the city.

“It would be great, and it just makes sense,” he said.

And as he prepared to take to the streets this Friday for the Year of the Horse, 4712, Chan did also mention his disappointment with the turnout for last year’s street parades. Chinatown just wasn’t packed the way it historically has been, and he wasn’t sure why.

Maybe that “evolution” of Chinese tradition — or perhaps more like an erosion — is finally taking its toll on the magnitude of these rituals. But maybe not.

In the end, Chan remains optimistic. After all, he’s still here, living on Mulberry St. and showing up to that old Freemasons Club haunt on Canal.

“Hey, even while some people around here are moving away to the suburbs, there are always new immigrants coming in to reinforce the culture,” he said. “The traditions are still here.”