New York City is currently experiencing an early childhood care crisis, but there are solutions being proposed to address several systemic issues.

In a letter addressed to Mayor Eric Adams and Schools Chancellor David Banks, the City Council’s Black, Latino, and Asian Caucus recently expressed its concerns about the city’s early childhood care and education system, particularly the 3-K programs. The letter highlighted the city’s “overly bureaucratic contracting processes, severely late contract payments, and insufficient enrollment and outreach efforts.”

The letter also touched on the closure of several early childhood programs, including Sheltering Arms, which closed last December. More than 1,400 childcare centers have closed in New York City since 2015, according to data disclosed at a recent education committee hearing held on childcare.

The state is set to lose $4.5 billion every year because of the childcare crisis, according to the letter.

The caucus proposed seven solutions to the city to address the 3-K system including: paying DOE contractors who provided child care services in the 2022 and 2023 fiscal years; improving salary parity between community-based organizations and DOE counterparts; developing a new enrollment system; releasing a new Request for Proposals that would expand Extended Day and Extended Year programs for parents who aren’t able to pick up their children in the middle of the day; and investing in a multilingual and culturally competent outreach campaign to educate New Yorkers on enrollment.

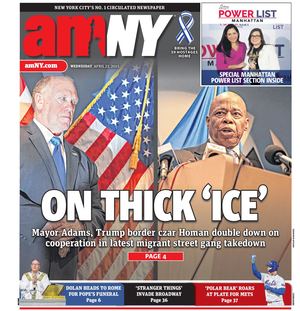

NYC families are in need of 3-K and early childhood programs but our communities are inadequately served by the current model due to late payments and insufficient enrollment practices, outreach efforts, and program design. The BLA Caucus sent the following letter to Mayor Adams: pic.twitter.com/7yvm65PFqd

— BLA Caucus (@BLACaucusNYC) March 1, 2023

The City Council’s Committee on Education held an oversight hearing on Feb. 16 on the proposed 3-K funding cuts and delayed reimbursements to early childhood providers. Education committee chair Rita Joseph raised reports of Pre-K and 3-K centers not being paid the full amount owed for their 2022 fiscal year contracts — a payment cycle that ended June 30 last year.

“We received ample testimony that DOE has not fulfilled his contract obligations to reimburse early childhood education providers,” Joseph said. “As a result, number of early childhood providers have permanently shut down. “

A Sheltering Arms spokesperson wrote in a statement to amNewYork Metro that: “Sheltering Arms was forced to close our Early Childhood Education programs due the Department of Education’s broken funding model, severely late payments and lack of consideration for low enrollment during the pandemic.”

Sanayi Beckles-Canton, executive director of the Chloe Day School and Wellness Center, an early childhood care program that serves Harlem children, has not received payments from a contract that was approved in 2021.

“As a result, we have had to take out loans to pay staff,” Beckles-Canton. “We’ve had to lay staff off. It is important that we get clarity, understanding, and cohesiveness among the different city agencies that support us.”

Early childhood providers were owed $460 million by the city’s Department of Education for work that was performed during the 2022 fiscal year. Kara Ahmed, the DOE deputy chancellor for early childhood education, said the city had faced “a very large issue” with more than 4,000 unpaid invoices totaling $460 million from the 2022 fiscal year. The city has since paid $122 million of the amount owed, Ahmed said.

Jennifer March, executive director at advocacy organization at the Citizens’ Committee for Children of New York, said in order to stabilize and strengthen the city’s early childhood education system, the city must immediately fast track delayed payments to contractors and increase advance payments, while also converting and expanding 3-K childcare seats.

“We have been extremely concerned about horrifically late payments from the DOE to contracted childcare providers that just destabilize the system and make it difficult to sustain services,” March said. “It’s really urgent that the DOE gets staff up and maintain staff, and also ensures that as they overcome late payments for fiscal (year) 2022, they address the current payment delays for the fiscal year we’re in.”

Councilmember Julie Menin (D-Manhattan) introduced a bill in December that would require the city’s education department to report every month on payments to early childhood care and education providers. The legislation would highlight the number of invoices in total, the number of invoices paid in full or partially paid, and the average amount of time it takes to process payments.

“My office has heard from early childhood care providers that have been left unpaid by DOE and are in danger of closing,” Menin said at the February education committee hearing. “We are in a childcare crisis.”

Amaris Cockfield, a spokesperson for the Mayor’s Office, said the city rolled out a new program, ContractStat, as an oversight initiative to address issues before they surface, and launched the 12-week ‘Clear the Backlog’ initiative to help get nonprofits with overdue bills paid for their work.

A Different Solution: Universal Child Care?

Councilmembers Jennifer Gutiérrez (D-Brooklyn/Queens) and Kevin Riley (D-Bronx) introduced a bill on March 2 to create free Universal Child Care in New York City. The plan, within a proposed five-year timeline, would establish free and expanded childcare for children six weeks to five years old, including undocumented children, increased workforce support and benefits for childcare providers, and creates grant programs to create new facilities.

The bill aims to lessen the financial and logistical burden of childcare for families and expand the early childcare workforce. The bill would create a separate office of childcare and ensure pay parity between childcare providers and DOE teachers and potentially convert thousands of vacant commercial and community spaces into childcare locations.

“They’re having difficulty in retaining good people,” Gutiérrez said. “The city doesn’t pay them on time. Every day the city is not paying these folks on time, we are a debt to these providers.”

Gutiérrez called the city’s 3k and 4k application process “very lengthy.” Having faced challenges herself navigating the city’s childcare system with her 15-month-old daughter, Gutiérrez continues to host roundtables with providers and parents. She’s learnt along the way that working parents, particularly those who work nights and weekends or want to keep sibling children together.

“It was a challenge and even I was on a waiting list,” Gutiérrez said. “Existing childcare systems or daycare systems don’t necessarily serve everyone. We have the reality of non-traditional hours.”

In a statement made on Feb. 15, Speaker Adrienne Adams wrote about the need for state funding for Pre-K in New York City.

“While the Executive Budget includes funding to expand Pre-K around the state, New York City is not guaranteed access to these funds,” Adams said. “We would hope that our foresight on early childhood education through 3-K and Pre-K is rewarded with needed state support.”

The next hearing on the Universal Child Care bill will be in April, according to Gutiérrez’s office.