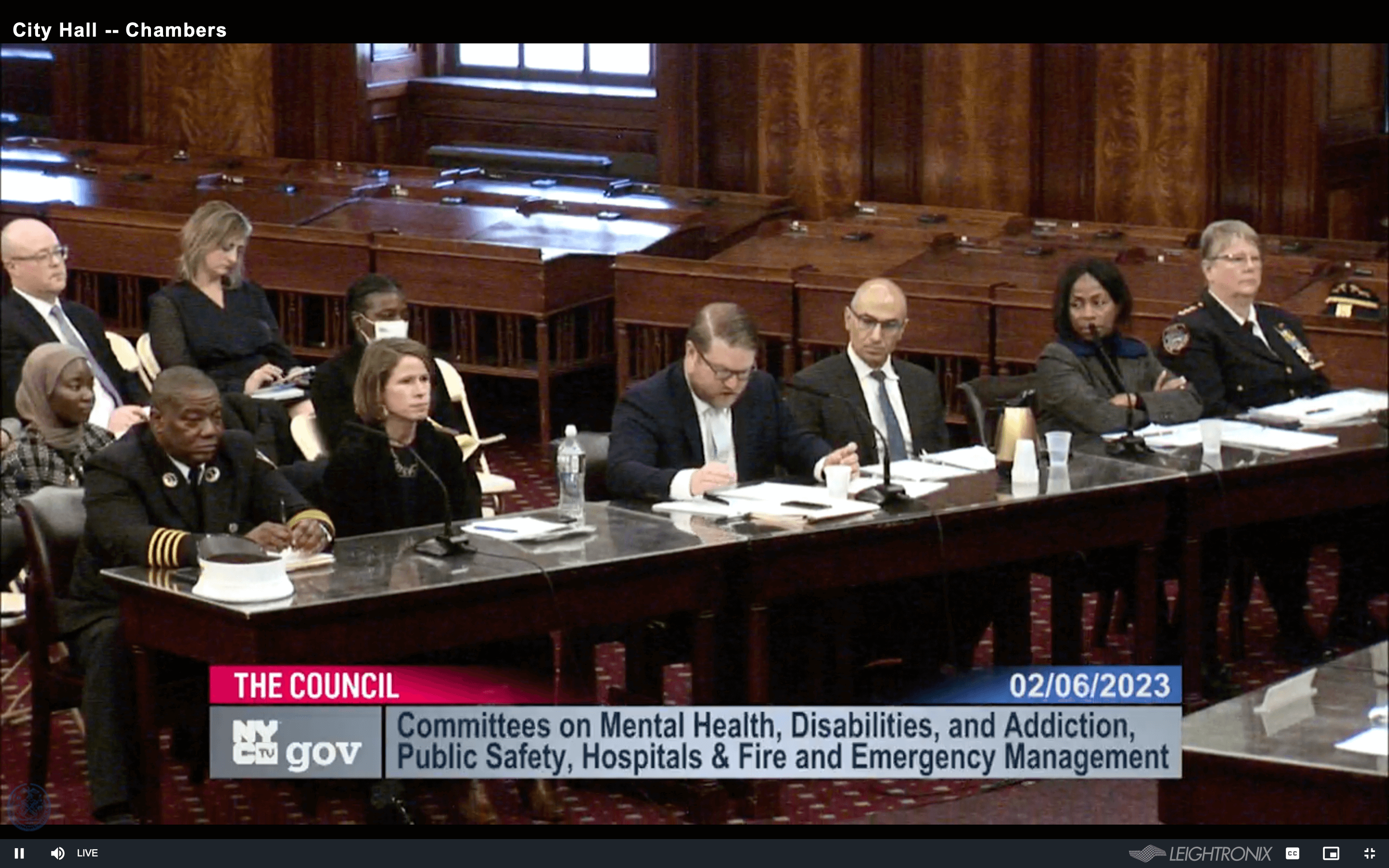

Several City Council committees came together on Monday to publicly examine Mayor Eric Adams’ recent directive to have police and emergency medical workers involuntarily hospitalize those on the street deemed too mentally ill to care for themselves.

On Feb. 6, members from the Council’s various health and public safety committees met to address the mayor’s controversial directive, announced last November. In it, hizzoner instructed first responders and health care professionals to start involuntarily bringing to a hospital anyone who appears to be a danger to themselves due to an inability to care for their “basic needs.”

The public hearing drew hours of criticism from mental health, peer advocates and some City Council members themselves, as well as family members of people who were killed by police during mental health crises.

By the end of the hearing, two new bills had been introduced — one regarding additional police training on engaging with people on the autism spectrum, and another mandating a city-run online mental health services portal for those seeking help.

“Mental health has been one of the most overlooked and neglected issues in our healthcare and justice system,” said Brooklyn Council Member Mercedes Narcisse, who chair’s the Council’s Committee on Hospitals.

Narcisse, who represents Brooklyn’s 46th District, introduced the bill which would require members additional NYPD training. If enacted, that training would include developing interpersonal skills to safely respond to emergencies involving people with autism.

“[The New York City Police Department is] usually the first to arrive from the response team, who often lack proper training in interacting with individuals with developmental disabilities, which could further escalate the situation, jeopardizing the lives of the officers, the individual suffering from the crisis, and the people involved.”

Manhattan Council Member Shaun Abreu (7th District) introduced a bill that would require the Mayor’s Office of Community Mental Health to create an online portal and a printed resource guide of available mental health services in the city.

“Access to services is critical, but sadly, I hear from constituents who are facing barriers to care due to lack of information and lack of options when it comes to paying for care,” Abreu said. “I’m hopeful this legislation will ensure that all city resources are centralized in one place for maximum benefit to those in need.”

‘It was traumatizing’

“The Mayor’s plan for involuntary hospitalization is not a solution to our City’s homelessness crisis,” Brooklyn Councilmember Shahana Hanif (39th District) said. “If anything, it simply creates a revolving door for unhoused New Yorkers to cycle in and out of our overcrowded hospital system, never truly receiving the help they need. I’m glad our Council is fulfilling our oversight responsibility to investigate this legally dubious and inhumane directive.”

Evelyn Graham-Nyaasi, a peer advocacy specialist at the mental health advocacy group Community Access, asked the City Council to reject Adams’ directive to expand the use of involuntary hospitalization.

Graham-Nyaasi described her run-in with police officers who responded to a 911 call at her residence: “Someone said I had a knife. I didn’t have a knife. I didn’t argue and fight with them because I didn’t want to be harmed or killed. So I followed their instructions. I ended up involuntarily hospitalized at Bellevue (Hospital). I was placed in a room that had people screaming and yelling, and we were locked up like animals. It was traumatizing. And it still affects me today. Because I didn’t know my rights, I wasn’t released until two weeks later.”

Because of this incident, Graham-Nyaasi said she’s learned the power that peers, people who have lived mental health experiences, can have if they were involved with emergencies rather than police.

“I firmly believe that all mental health crisis response teams must be led by peers,” Graham-Nyaasi said. “Peers can make an individual feel safe because they understand what they’re going through. Trust must be developed and that can only happen with peers who have lived experience.”

The directive, explained

Last December, Adams issued a directive to first responders, including NYPD, firefighters, and EMS workers, and mobile crisis teams, which comprise also of clinicians, on involuntarily transporting a person experiencing mental health crisis to a hospital for evaluation. The involuntary transfer would occur “when a person refuses voluntary assistance, and it appears that they are suffering from severe mental illness and are a danger to themselves due to an inability to meet their basic needs,” Adams said. “Basic needs” is defined as needs essential for survival: “food, clothing, shelter or medical care.”

Adams’ Psychiatric Crisis Care Legislative Agenda calls for allowing a broader range of licensed mental health professionals to staff the city’s mobile crisis teams, and for a broader range of trained professionals to perform psychiatric evaluations in hospitals. There are currently 24 mobile crisis teams across New York City. These teams conducted 42 involuntary transfers last December, including of housed people.

When people are involuntarily brought to hospitals, they are given medical and psychiatric evaluations, an emergency room stay of up to three days, and a thorough assessment. Outreach is conducted to find out more information about their history. Then, a discharge plan is created which could include follow-up care and appointments at an outpatient clinic or program, wrap-around services like care management, care worker assignment, and a critical intervention team working with the individual for up to nine months, according to Omar Fattal, System Chief for Behavioral Health and co-Deputy Chief Medical Officer at New York City Health and Hospitals.

But Ellen Trawick, the mother of Kawaski Trawick who was killed in 2019 by NYPD at a supported housing facility in the Bronx, testified at the hearing and told the City Council she was appalled to learn that Adams gave police a directive to “sweep people up the street and force them into hospitals just because officers decide that they are mentally ill or homeless.”

“I’m calling on the City Council to stand with me and my family and other family members who have lost their loved ones to NYPD in opposing Mayor Adams’ forced hospitalization,” Trawick said. Instead, New York City must focus on making sure that people get the care they need by investing in community-based services.”

Removing barriers

Adams’ agenda aims at removing 11 legal barriers to psychiatric crisis care. Adams proposed expanding the authority of first responders to involuntarily transfer a person if their mental illness was “likely to result in serious harm” and also if mental illness leaves “a person unable to meet their basic survival needs.”

The directive would also give mental health staff at shelters and other adult care facilities the authority to direct involuntary removals of a resident in a psychiatric crisis. The agenda acknowledged the need for more mobile crisis outreach teams, and recommended that teams also include licensed mental health counselors and licensed marriage and family therapists.

Approximately 87% of patrol officers, 91% of transit officers, and 89% of housing officers are trained in responding to mental health emergencies. Approximately 1% of all mental health calls in 2022 resulted in arrest, according to NYPD Chief of Interagency Operations Theresa Tobin.

“Before this plan, these removals were done without a coordinated approach across agencies. First responders and clinicians often followed their own protocols that were usually unknown to one another,” said Jason Hansman, deputy director of mental health initiatives and crisis response at the Mayor’s Office of Community Mental Health. “With the mayor’s new policy, everyone is working off of the same playbook.”

Adams said in a one-on-one interview with amNewYork Metro last December that was on his visits around the city’s subway with Ashwin Vasan, the city’s Department of Health and Mental Hygiene commissioner, that he realized people who worked in mental health were unaware of how to exercise their authority during mental health emergencies. Adams said the city needed 1,000 hospital beds in private and public hospitals focused on medication and stabilizing someone’s condition.

Adams also said that he knows that tele-medicine can assist people who are going through crisis to speak with a psychiatrist or psychologist and get the necessary assistance they need.

“Our goal is to catch individuals upstream before they reach the point that they are in the street unable to care for themselves or even living behind closed doors and dealing with severe mental health illnesses,” Adams said. “It’s difficult to say that this problem is going to be eradicated in a year, two years.”

U.S. District Judge Paul Crotty blocked a motion on Jan. 30 filed by mental health advocacy groups last December to stop Adams’ involuntary hospitalization directive.