Months after 10 northern Brooklyn police precincts cut off their radios from the press and public, the City Council will eye the NYPD’s broader plans to encrypt their devices at a Nov. 20 hearing.

The NYPD maintains that radio encryption keeps their officers and the public safe from unauthorized interference, while members of the media and public officials describe the move as “the most regressive transparency policy in the history of New York City.”

NYPD officials say they expect the entire police department will be using encrypted radios by the end of 2024, but have not revealed when or if members of the media or news apps will have access to radio communications. The cut-off of radio transmissions would also deprive 2.5 million Citizen App followers of breaking news in their community.

Journalists, the most effected group, will now be able to voice their opinions on radio encryption and the current state of NYPD transparency at the hearing. The live hearing will be held on Monday, Nov. 20, 1 p.m. at 250 Broadway, 16th floor in Manhattan. To register to speak or to file a statement with the City Council, go to council.nyc.gov/testify.

NYPD Assistant Chief Ruben Beltran, head of NYPD Information Technology Bureau, is scheduled to testify. Beltran led the $1.5 billion NYPD radio upgrade that began in 2020, in addition to coordinating many other technology-driven police upgrades. That includes the controversial facial recognition system that had drawn anger from the City Council and spurred the Public Oversight of Surveillance Technology Act, (POST).

A hearing on the POST Act has been deferred three times due to the NYPD requesting the postponement. Some council members believe the NYPD is intentionally avoiding the hearing.

“We are gratified that the City Council has decided to address this matter of great importance to both the public’s right to know and to maintain the transparency of the NYPD,” said Bruce Cotler, president of the New York Press Photographers Association. “We will be informing the council on matters that they have purview on and that they vote on each and every year in their budget. We believe they don’t always understand what the NYPD is doing and we intend to put a spotlight on this issue.”

A matter of ‘trust’

The NYPD has shared their frequencies with the press since the 1930s, and provided media outlets with much of their direction to many important stories — including live reporting of the Sept. 11, 2001 terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center, and Hurricane Sandy in 2012, which killed 43 people and wiped out hundreds of homes due to flooding and massive fires.

The ability to listen to police radios has also enabled the media to serve as a check-and-balance on the NYPD, allowing for independent coverage of stories such as the chokehold death of Eric Garner as he was arrested for selling cigarettes Staten Island in 2014; the 1999 shooting death of Amadou Diallo of the Bronx, who was shot 41 times by officers who thought the wallet he held up was a weapon; and the police shooting death of Sean Bell in his car in Queens on the eve of his wedding in 2006.

Currently, the NYPD has only promised to provide “delayed” monitoring of radios of up to 30 minutes that would prevent “malevolent” listeners from using their communications to commit crimes.

Members of the media have insisted upon “real-time” radio monitoring for credentialed media. But the NYPD said they “don’t trust” many of the new members of the media because “we no longer vet them.”

The NYPD lost their ability to credential or to discipline members of the media after the City Council voted to remove press credentials from their responsibility after Black Lives Matter protests in 2020, during which a number of credentialed journalists were roughed up or even arrested by officers.

As a result, press credentials are now issued by the Mayor’s Office of Media and Entertainment. Representatives of that office have also been called to testify at the Nov. 20 hearing.

Nine press organizations have mobilized under the banner of the New York Media Consortium with the sole purpose of convincing the NYPD and the city to allow media organizations to continue to receive police radio transmissions in “real time.”

The consortium maintains that encryption will make the NYPD in sole control of the daily narrative. The ability to monitor has been the crux of news coverage for more than 90 years and its elimination represents a major regression in transparency, leaders maintain.

Dakota Santiago, a Freedom News TV photographer and videographer, said he recently visited San Francisco, where most police radios are encrypted. He said he picked up on a nondescript Citizen app notification on Oct. 30 of a police incident and followed the leads.

He soon found out that a man had been throwing pipe bombs and Molotov cocktails out the window of his car at police in a wild chase through the city — but nobody from the press knew.

“People were asking whether there was some sort of a police chase, but nobody knew that a guy was throwing bombs out of his car window so there was no alert or anything from the police or anyone,” said Santiago, who has been chasing news since 2020. “There’s no way to know if there is high crime or not. Hearing the radio calls helps us to keep community calm. In the Bronx, there could be a shooting every night and we can verify by listening to the radios. Once encrypted, you won’t know if there was shooting and then we can’t stop misinformation – it’s a whole new can of worms because you will never know if the police are on the level with us.”

Elected leaders respond

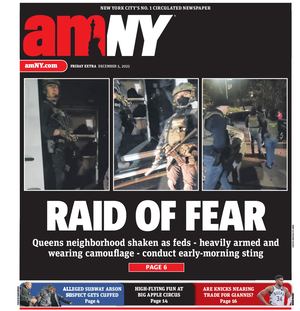

The NYPD has so far encrypted 10 precincts in Brooklyn North from Williamsburg in the west to East New York in the east. Members of the media and public hear nothing on those frequencies and must rely on city-wide notifications, EMS and fire radios for any breaking news.

The Citizen app has also lost the ability to confirm breaking news in some of these communities, a number of which traditionally have higher crime rates, leaving their incident maps bare. Notifications of incidents in these communities can take hours if not days before homicides, shootings and other major occurrences are known to the public.

City Comptroller Brad Lander sent a letter to the NYPD expressing concern about radio encryption and seeking answers regarding the encryption program and why the department has so far failed to provide access to the media for those precincts already encrypted.

Lander said in his statement: “NYPD reportedly intends to expand this radio encryption citywide, but has failed to articulate its plans to ensure that the media will maintain access to critical, real time information. This policy change will mean that the NYPD may exclusively control whether a particular newsworthy event reaches the public domain.”

The NYPD did not yet respond to Lander’s inquiry, but did issue this statement:

“The safety of our first responders and the community will always remain the NYPD’s top priority. The Department works day-in and day-out to be transparent and build trust with the public. We are continuing to explore whether certain media access can be facilitated, including utilizing methods that are already being used in jurisdictions with encrypted radios.”

Media leaders applauded Lander for his efforts to gain access for media to encrypted communications.

“RTDNA is gratified that Comptroller Lander is taking an interest in ensuring the public’s need to know what’s happening in the neighborhoods of New York City,” said Dan Shelly, president and CEO of the Radio Television Digital News Association (RTDNA) Foundation and a member of the NY Media Consortium. “The NYPD motto is ‘Courtesy. Professionalism. Respect.’ The wanton encryption of all NYPD radio transmissions accomplishes none of those things.”

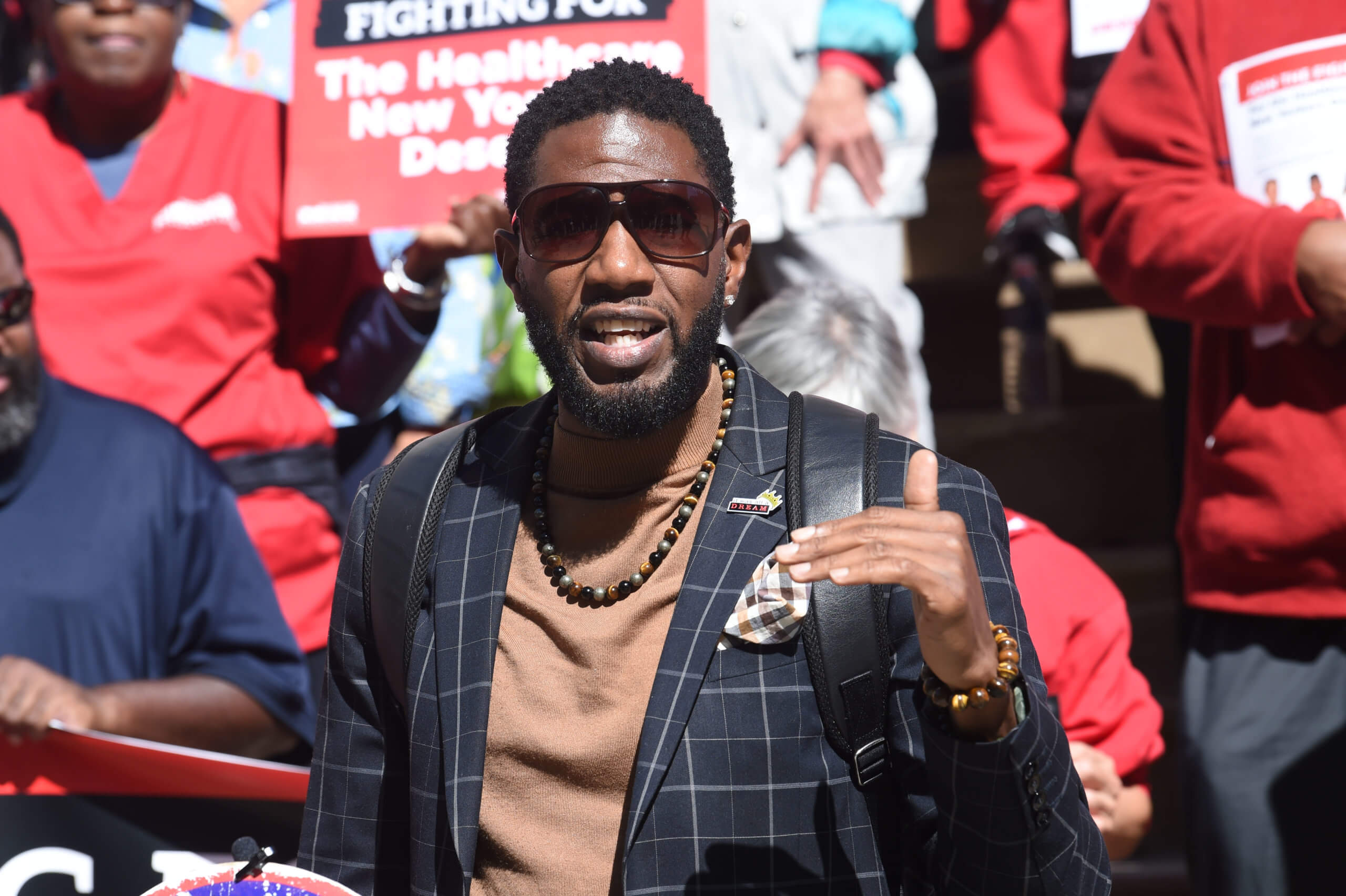

Other government officials have weighed in with most council members taking a listening approach without taking a position. Public Advocate Jumaane Williams, however, took a more strident view.

“This is a troubling trend, and the antithesis of the transparency that we need in law enforcement,” Williams said. “I’ve heard no rationale for why the press or the public should have their access to these airwaves suddenly restricted – public safety requires public accountability.”

To date, Mayor Eric Adams has not taken a position on encryption only promising to “listen to concerns” of the media.

Deputy Mayor for Public Safety Philip Banks, a former NYPD chief of department, has had a strong hand in NYPD policy. As of press time, Banks has yet to comment on the encryption policy.

Read more: Thousands celebrate New Year’s Eve 2024 in Times Square