By SCOTT M. STRINGER

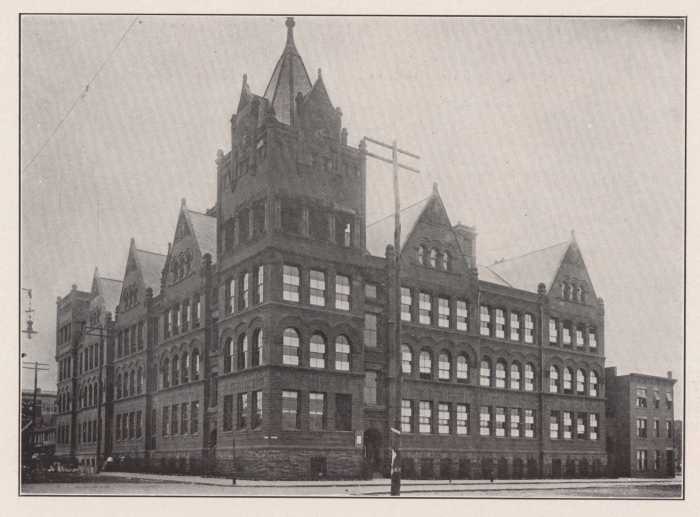

For the third time in two years, New York City parents and educators in District 2 are facing a frustrating and futile ritual: The Department of Education is planning to rezone school boundary lines in an area stretching from Lower Manhattan to the Upper East Side, and the chaos resulting from uncertainty over these plans should be no surprise.

Simply put, the city has done a dreadful job of anticipating and dealing with booming population growth in District 2 where schools are notoriously overcrowded. D.O.E.’s plans to mitigate the problem have been piecemeal at best. They fail to offer long-term solutions and infuriate parents who do not know with any certainty which schools their children will attend, or if neighborhood choices are even available.

This year, as in the past, confusion reigns over D.O.E.’s zoning changes: In Tribeca, parents have expressed concerns about children being sent to a school in the West Village; in the West Village, parents are angered by plans that would send their children to a school in Chelsea. All of the plans now under consideration — which have yet to be approved — amount to the largest rezoning this district has ever seen.

Rezonings are necessary in some cases, but increasingly they feel like D.O.E.’s default strategy for addressing school overcrowding. Overuse of this practice wreaks havoc on families, and if we don’t create more new schools, no amount of shifting lines will resolve the broader overcrowding problems plaguing our city.

My office has tracked this problem for years: In our “Crowded Out” report we revealed that in four of Manhattan’s most overcrowded communities — Lower Manhattan, Greenwich Village, the Flatiron District and Upper East Side — the city had approved residential construction that would add 2,000 school-age children but only 143 new classroom seats for just one neighborhood; the others got none.

A subsequent report, “Still Crowded Out,” showed that, in the first eight months of 2008, the city issued permits for more than 6,500 new residential units. New York City’s own methodology estimated this would result in 1,100 new school-age children, including 900 in the four overcrowded neighborhoods mentioned above.

The price for D.O.E.’s unwillingness to address long-term needs includes cuts to prekindergarten programs, the elimination of art and music classrooms, and the relocation of middle schools out of their communities to meet increased elementary school seat demand. Squeezing more kindergarten classes into already overcrowded buildings has forced some schools to collapse their upper-grade classes, worsening overcrowding.

This model is not sustainable. But there are clear steps we can take to reduce these problems. First, I have repeatedly recommended reforming the “Blue Book — D.O.E.’s annual report on school capacity and enrollment — because it is based on flawed methodology. Blue Book formulas underlie D.O.E.’s distorted picture of space in schools; they rarely reflect the reality faced by educators, parents and students every day.

Second, we should bring the Department of City Planning and city comptroller into the school-space planning process. Planning staff could provide annual projections based on appropriate data. The Comptroller’s Office could conduct school capacity needs analyses, estimating new school seats needed five and 10 years down the line —with the goal of providing enough rooms for art and music, and reducing overcrowding.

I urge all of you who share my concerns to speak out at upcoming District 2 Community Education Council meetings and get involved in the long-term planning process. We have seen a number of instances in which parents have identified and successfully advocated for new schools. Parents know their communities best, and we need them to be a part in this process. The stakes have never been higher for our kids, our schools and our city’s future.

Stringer is the Manhattan borough president