The city’s landmark building emissions law, Local Law 97, is set to go into effect next year, and the complex rule-making process has set off a frenzy of lobbying activity aimed at influencing and potentially weakening the statute aiming to help combat climate change.

Local Law 97, passed in 2019, is one of the most ambitious local climate laws in the world, requiring the owners of buildings greater than 25,000 square feet to meet strict regulations on carbon emissions starting next year, requiring many of them to retrofit their properties or face stiff penalties each year.

The law is set to go into effect in January, with the first compliance reports for affected property owners required by May 2025. Buildings must start to comply with the emissions standards next year, and future compliance periods in 2030 and beyond will require owners to meet even stricter carbon emission limits.

But before the law can be implemented, the city’s Department of Buildings (DOB) must finalize the complicated array of rules governing the vast program, which is not only turning out hundreds of New Yorkers to meetings but is also leading to the disbursement of big bucks in lobbying expenditures.

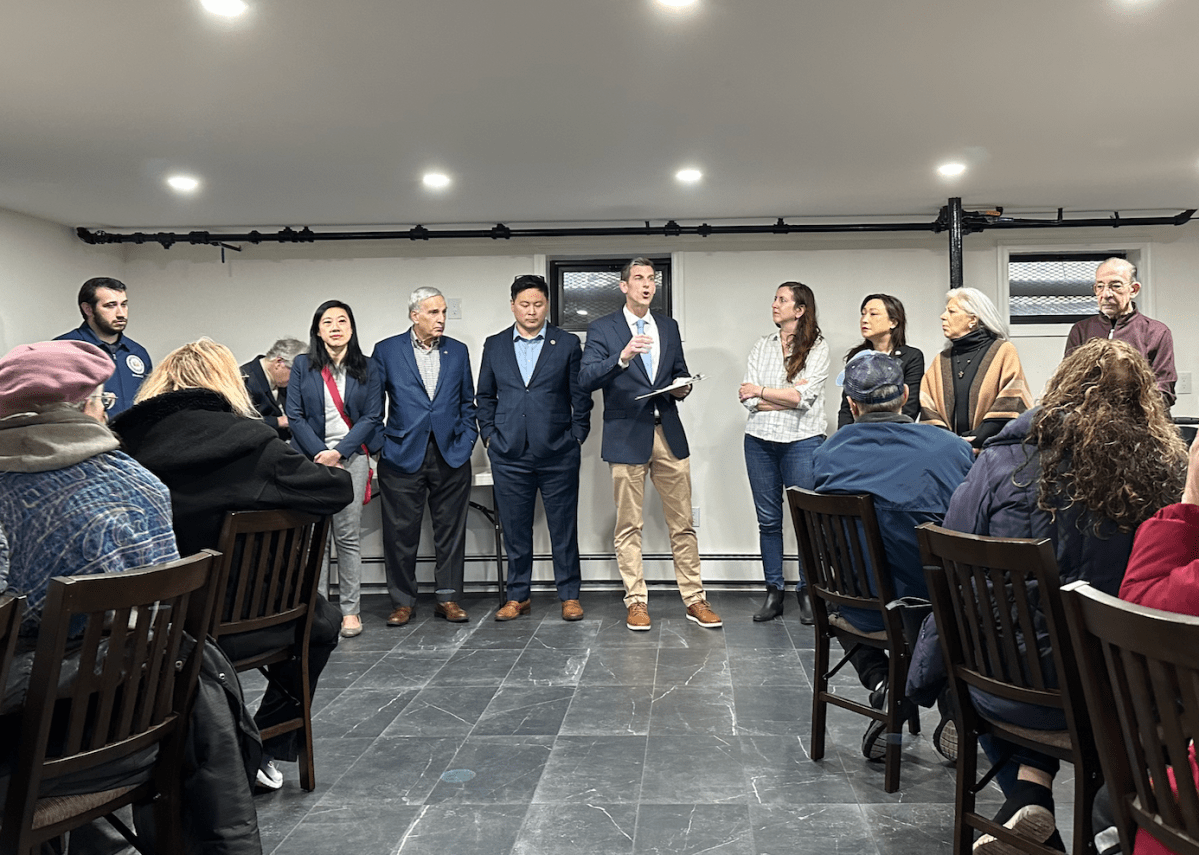

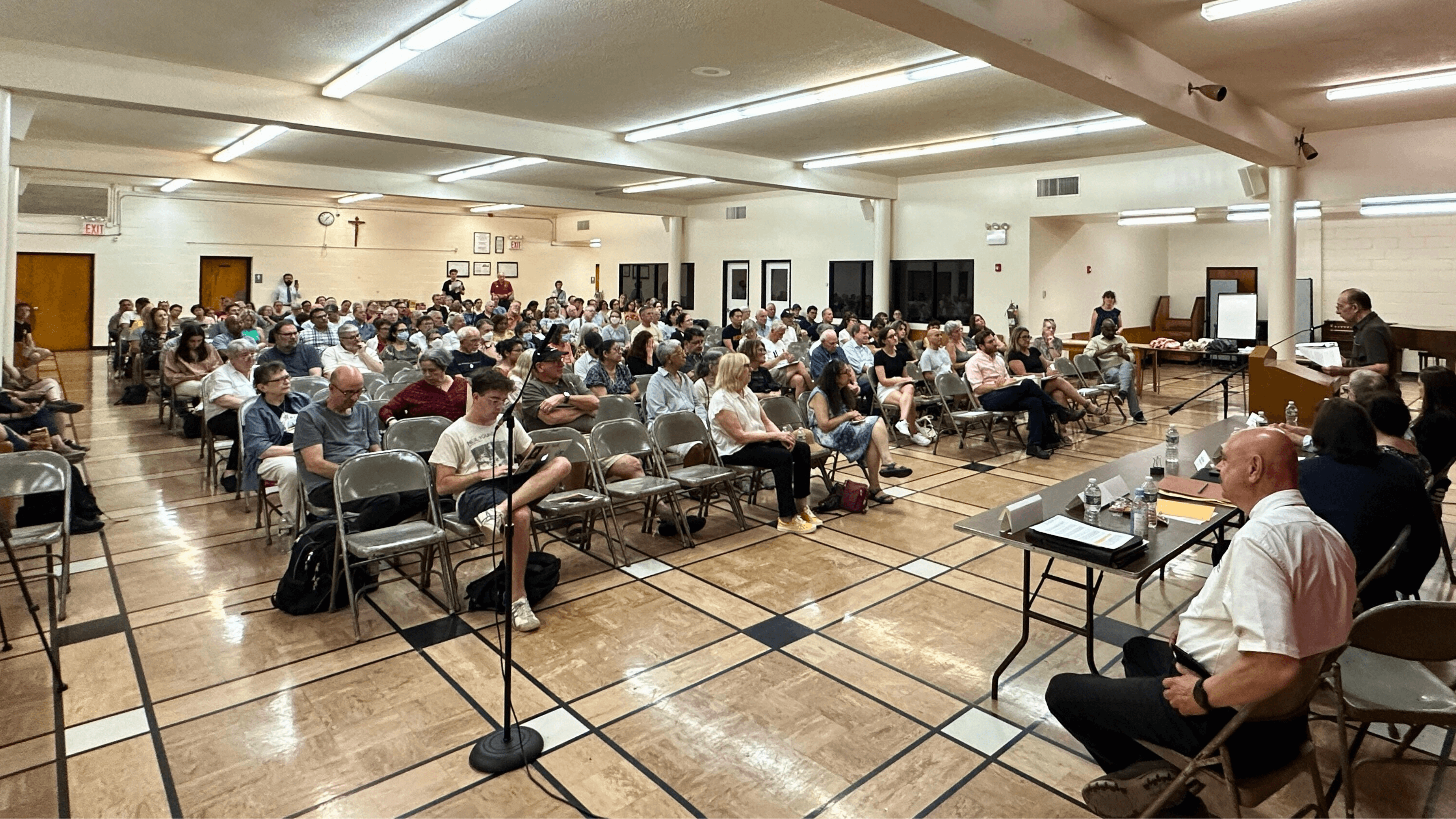

Some of the loudest voices seeking to weaken the statute are co-op and condo owners, who have packed raucous town halls across the city in recent months bemoaning what they say will be ruinous penalties for largely working and middle-class homeowners.

But while the co-op owners present themselves as having little sway and political influence, they do have some powerful friends.

Louder voices come forth

One group, Homeowners for a Stronger New York, which is an ally, presents itself as a grassroots collective of co-op and condo owners concerned by the high cost of complying with the law come next year.

It has spent hundreds of thousands of dollars on television ads, digital ads, mailers, and lobbying expenses supporting a bill in Albany that would provide property tax breaks for building owners who make emissions-reducing retrofits to their properties.

But left out of the ads is that Homeowners for a Stronger New York gets all of its funding from a single source, another anodyne-sounding group called Taxpayers for an Affordable New York, according to state lobbying records. Just over $300,000 has changed hands between the two groups since May.

According to its publicly-available 990 tax returns, Taxpayers for an Affordable New York lists as its president James Whelan, who is also president of the Real Estate Board of New York (REBNY), the powerful and influential trade group representing the city’s landlords and developers. REBNY denied controlling the group when asked by amNewYork Metro.

Still, REBNY has made no secret that it is lobbying on Local Law 97, which represents one of the largest and most expensive mandates on property owners in the city’s history. The group commissioned a study that was released January that found 3,700 properties could be out of compliance next year and collectively face $200 million in fines, rising to $900 million among 13,500 non-compliant buildings by 2030, when buildings subject to the requirements must cut their carbon emissions by 40% compared to 2005 data.

However, the group’s findings for 2024 represent just a sliver of the city’s approximately 40,000 buildings covered under the law, while the tougher 2030 emission standards are still years away.

“[The year] 2024, by design of the law, was meant to be a period where we get the regulations going…and we get prepared for what is the much more aggressive cap in 2030,” said John Mandyck, CEO of the Urban Green Council, a nonprofit focused on policy for decarbonizing buildings. “There’s no question the law is tough, but it’s completely doable, and we really have no choice because the climate isn’t waiting for us to act.”

The number of buildings getting in compliance with the law continues to grow. When the law was initially passed in 2019, the DOB estimated that 20% of the buildings covered by the legislation would not meet their emission limits in 2024 and would face potential penalties. The DOB announced this week that the percentage had dropped to 11% based on 2022 data.

While most building owners will meet the 2024 requirements, older co-op buildings in particular will struggle to comply. Modern condo developments and office buildings are mostly in compliance.

Seeking a ‘good-faith effort’ to avoid penalties

REBNY is hoping DOB adopts a broad definition of the law’s so-called “good-faith effort” – during the rulemaking process.

A broad definition would provide the owners of non-compliant buildings with the ability to avoid penalties if they are able to show that they have taken steps to make their buildings more sustainable.

“I think our concern is Local Law 97 is gonna lead to a lot of penalties instead of a lot of emissions reductions,” said Zachary Steinberg, REBNY’s senior vice president of policy, in an interview with amNewYork Metro.

But Pete Sikora, climate campaigns director with New York Communities for Change, worries that a broad definition of good-faith effort, even if well-meaning, could effectively provide a lucrative loophole for the city’s largest landlords and significantly weaken the purpose of the legislation.

“That’s the $64,000 question for the law,” Sikora told amNewYork Metro. “If you create a system where good faith is a definition that can be easily manipulated by a group of consultants and lawyers, then you create an easy out for landlords who don’t want to reduce pollution for their buildings through energy efficiency.”

The definition needs to be strict, advocates say, or else the law will be ineffective, and its emission targets won’t be met. The purpose of the bill is to reduce building emissions by 40% by 2030 — compared to 2005 levels — and 80% by 2050.

Many co-op and condo owners are also seeking clarity on what “good faith” means, but like REBNY are looking for latitude.

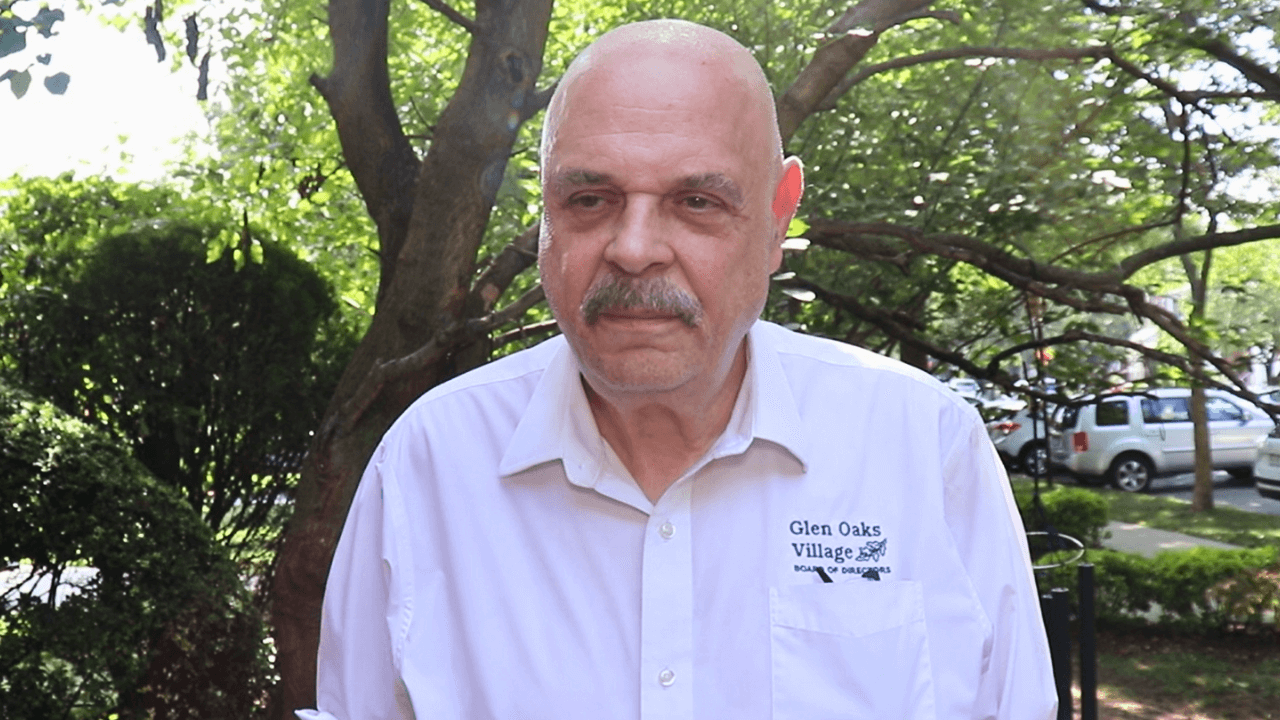

In contrast to the advocates, Bob Friedrich, co-op board president at the 2,900-unit Glen Oaks Village in Queens, argues that good faith efforts can be easily documented to ensure that owners are not flouting the rules.

“I think a good faith effort can be corroborated very, very easily,” Friedrich told amNewYork Metro. “Did they spend money, did they do it properly?”

Suing to kill the law entirely

Friedrich believes that co-op owners should be exempt from the law, arguing that individual unit holders will be charged thousands.

“There’s never been a shred of evidence to show that co-ops are even marginal contributors of pollution. Maybe the big commercial buildings are, but there’s been nothing, not a shred of evidence,” he said.

Friedrich, in fact, is calling for the law to be scrapped entirely.

“I think the law should be overturned, I think the law was not well thought out,” he said.

Friedrich says that his development faces penalties of $394,000 per year from 2024 to 2029, before going up to $1.5 million in 2030. He says for Glen Oaks Village to fully comply with the law in years to come — and go fully electric — it will cost $50 million or $20,000 per unit.

He is a co-plaintiff in a lawsuit against the city seeking to have Local Law 97 rendered unconstitutional and overturned. The lawsuit claims that Local Law 97 is preempted by the state’s 2019 Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act, which requires the state’s emissions to be reduced 85% below 1990 levels by 2050. The suit also alleges that the law is too vague and is an undeclared tax.

Friedrich is one of four plaintiffs who are part of the lawsuit, along with his Glen Oaks Village co-op, as well as the 200-unit Bay Terrace Co-Op and its board president Warren Schreiber. They are being represented by Randy Mastro, a high-powered and highly-compensated litigator.

Mastro is currently representing New Jersey in its fight to overturn New York’s congestion pricing program and is also defending Madison Square Garden against lawyers who say they were unreasonably banned from the venue. He also represented New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie during the infamous BridgeGate scandal at a $650-per-hour tab.

The plaintiffs are, as it turns out, not paying Mastro’s hefty legal bill, but they won’t say who is.

Friedrich said he didn’t know who’s paying the legal fees; Schreiber told amNewYork Metro that there’s an outside “funder” but wouldn’t say who, contending he signed a retainer agreement forbidding disclosure of the benefactor. Mastro did not return a request for comment.

Friedrich and Schreiber are the founders of the Presidents Co-op and Condo Council (PCCC), which self-describes as a “problem-solving think tank” and forum for board presidents to discuss common issues and solutions. The group has been hosting town halls all over Queens for worried residents to learn about Local Law 97 and register concerns.

But Sikora argues that they have been havens of misinformation and fearmongering about the law. For instance, he said that the penalties associated with non-compliance between 2024-2029 are being exaggerated, and that building owners have to upgrade their infrastructure periodically in any case.

For instance, in Friedrich’s Glen Oaks building, the penalty based on the figures he has presented — $394,000 per year — would equate to $136 per unit per year, or $11 per month, spread across the 2,904-unit development through 2029. While significant upgrades would be needed in years to come, the costs could be spread over time, and ongoing maintenance is needed in any case, Sikora argues.

Geoff Mazel, a lawyer representing PCCC, told the audience at a June town hall in Douglaston that “nobody is looking out for co-op and condos.” He claims tenants in rent-stabilized apartments are well represented but co-op and condo owners are not.

“You can turn the news on and if [the Rent Guidelines Board] say they want to raise rent 2%, it’s a front-page story,” he said, asserting that little is written about rising costs for co-op and condo owners.

The PCCC is not registered as a lobby group despite hosting the town halls. Mazel said the group is not required to register since the meetings are technically sponsored by someone else — such as elected officials or a co-op board — and its members are volunteers.

PCCC is not a party to the lawsuit, and so is technically not paying Mastro for his legal representation of its de facto leaders.

“This is a lawsuit over implementation of a law, and the people who have direct interests in it are plaintiffs,” said Rachael Fauss, senior policy advisor at the watchdog group Reinvent Albany. “But when you look at the web of activity here, at the end of the day someone is going to have to pay for it and someone is lobbying.”

A waiting game

The long rulemaking process is frustrating both property owners and environmental advocates. Building owners, for one, are seeking clarity on what exactly will be required of them regarding work on their buildings.

“With hundreds of millions of dollars in financial penalties set to begin in just a few months, we are concerned that many very important rules regarding compliance have still not been addressed and few tools have been offered by the City to help building owners reduce emissions,” REBNY said in a statement.

Advocates, on the other hand, are worried the lengthy delay could mean the Adams administration is bowing to the pressure campaign to soften it.

DOB, for its part, says that more rules, including those for noncompliance, will be publicized later this summer, and recommends building owners start doing retrofits now instead of waiting until the last minute. The term “good faith effort” will also be defined later this summer.

“Since we published our first major rule back in January, building owners have had all of the information they need to meet their emission reduction targets, and we are continuing to urge building owners to start their retrofit projects as soon as possible,” said DOB spokesperson David Maggiotto. “Our rulemaking process is proceeding on time and in full compliance with Local Law 97, and we will continue the inclusive, collaborative approach that has been a hallmark of the process since the beginning.”

Maggiotto insisted that “the city is fully implementing Local Law 97.”

Some city lawmakers have proposed delaying the implementation of the law by seven years so property owners, particularly co-op and condo owners, have more time to get into compliance.

But Sikora says the consequences of such a move would be dire, with the United Nations pressing members to undertake large-scale decarbonization and sustainability projects as the world approaches the “point of no return” on temperature increases.

“If that’s delayed, there’s no margin of error anymore, and then you get into increasingly dire global catastrophe,” Sikora said. “Every extra ton of climate pollution dumped into the sky, which we’re currently using as an open sewer, every extra ton matters.”

Michael Dorgan contributed to this article.

This story is part of “The Costs of Change” series that looks at Local Law 97.

Read more: 100s of Pigeons Netted in Washington Square Park Crime