BY BILL WEINBERG | New York has been drawn into the national culture war with Mayor Bill de Blasio’s appointment of a commission to review “symbols of hate” in the city. The towering statue of Christopher Columbus above the circle named for him is fingered as a possibility to go — eliciting inevitable outrage. Downtown Italian-American spokesman John Fratta stated wryly to The Villager: “In 1920, the Ku Klux Klan fought against Columbus Day. Now, in 2017, it’s the politicians.”

Downtown could also be affected — for instance, Sheridan Square in Greenwich Village. General Philip Sheridan was a hero of the Union side in the Civil War. But his later campaigns against the Plains Indians saw what would today be considered acts of genocide — most famously, the Washita River massacre of 1868, in which his troops set upon a sleeping Cheyenne winter encampment, killing some hundred, including many women and children. (The commander on the scene was the notorious Colonel George Custer.)

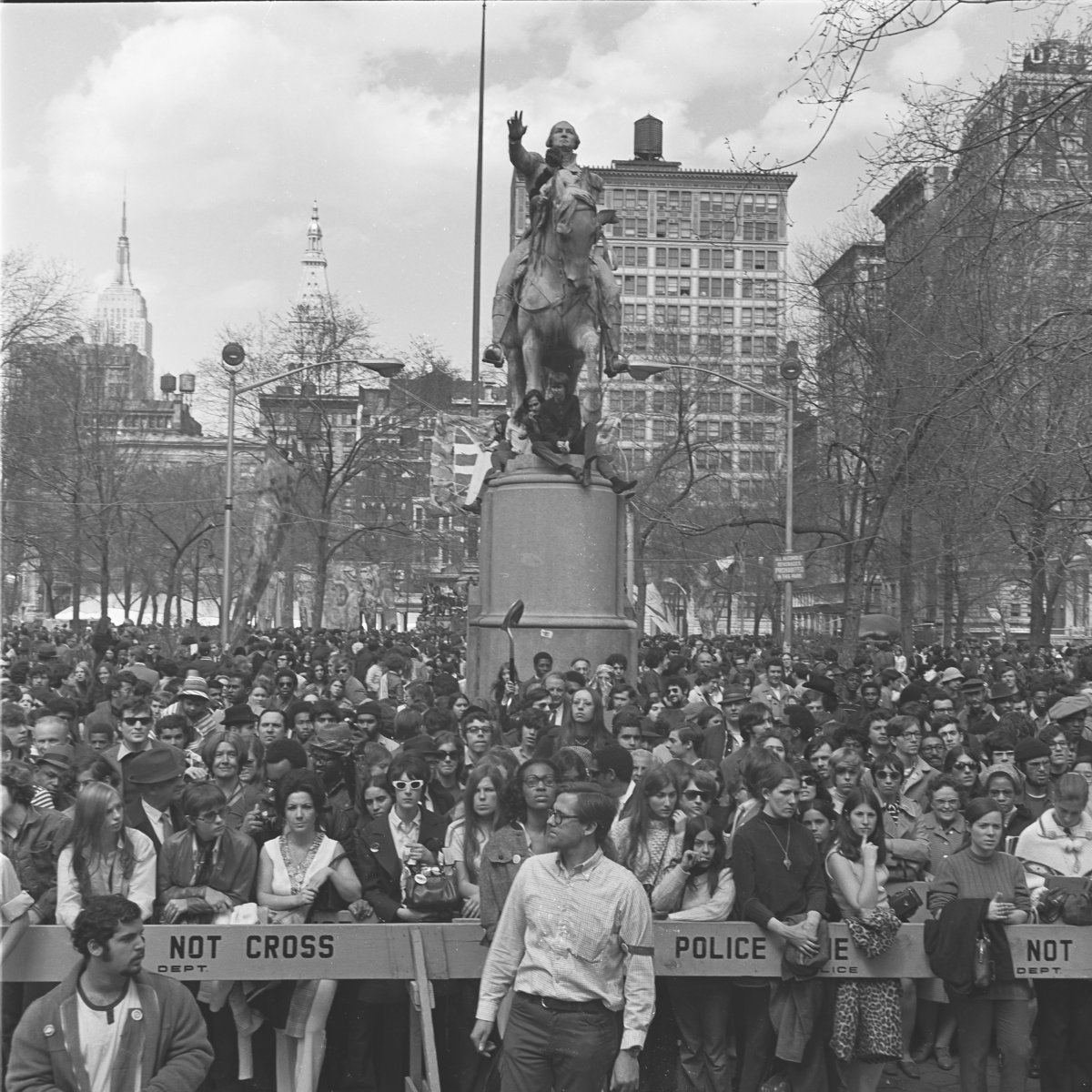

The statue of George Washington in Union Square has also been named.

This, of course, is all a response to the removal of Confederate monuments in the South, and the backlash seen in the deadly violence at Charlottesville. Trump provocatively asked if demands to remove statues of slave-owner Washington would be next.

Are those now raising such demands playing into Trump’s hands?

The emerging consensus to remove Confederate monuments is on firm ground, morally and tactically. Such a consensus regarding Washington and Columbus may yet arrive. But there are reasons the consensus is now arriving regarding the Confederate monuments.

Those were explicitly raised as symbols of white supremacy, and to humiliate blacks. They started going up in the 1920s, heyday of the Ku Klux Klan. Despite maudlin glorification of the “Lost Cause,” they were triumphalist markers of the Jim Crow order.

The Columbus statues were raised as symbols of Italian pride, and — as Fratta correctly notes — were opposed by the Klan, which then still hated Catholics. The Columbus monuments constituted markers of Italians in America becoming (at least) honorary “whites.” Of course the Klan was the last to recognize this social ascendance.

Columbus is inevitably a symbol of colonialism, but his statue was not raised as a symbol of “hate” — not as a conscious denigration of Native Americans, the way General Robert E. Lee was raised as a conscious denigration of African Americans.

The same distinction applies to Washington, the slave owner and Indian killer who looks down on Union Square.

Few New Yorkers know that Sullivan St. in Greenwich Village is named for General John Sullivan, who was dispatched by George Washington in 1779 to decimate the Iroquois Confederacy of Upstate New York. The Iroquois were officially neutral in the Revolution. But a few bands of one of the confederacy’s six constituent nations, the Mohawk, took up arms against the Continental Army —because the British had ordered a halt to settler colonization west of the Appalachians, a little-recognized root cause of the Revolution. For this, Sullivan was ordered to attack all six Iroquois nations, burning their villages, destroying their crops, sending thousands fleeing west. They finally reached British-held Fort Niagara, where many died during the harsh winter that followed.

This was the bloodiest of several campaigns of ethnic cleansing on the western frontier — a near-forgotten legacy of George Washington — that were a sideshow to the American War of Independence.

That an aristocrat with this ugly legacy is the pre-eminent symbol of national unity reveals much about our culture. But Washington’s image was not raised as a conscious symbol of white supremacy, as were those of Lee. (It should be noted that more than one of Lee’s descendants, including his great-grandson, are calling for his statues to come down, recalling that the Confederate general himself opposed the erecting of such monuments after the war as corrosive to restored national unity.)

Symbols can mean different things in different contexts. People who see Columbus only as a symbol of colonialism should grasp that Italians were once an excluded minority in the U.S., and the erecting of these statues was a signifier of their social integration.

But Italians should get that the context has changed, and that excluded peoples today see removing these very same statues as signifiers of their own dignity.

I’m half Italian, and my personal icon of Italian-American heritage is New York’s own Carlo Tresca, the anarchist and anti-fascist leader who was killed on 15th St. in 1943 on probable orders of Mussolini. But isn’t it inherently absurd to raise a statue of an anarchist?

The urge to purge relics of an oppressive past was taken to pathological extremes in China’s Cultural Revolution of the 1960s, when Buddhist temples were looted and sacked. But after Mao’s death, statues of the dictator who had unleashed the Cultural Revolution started coming down. Few today would argue this was a bad thing. The destruction of Stalin statues in Eastern Europe during the revolutions of 1989 is today openly celebrated.

And after the Declaration of Independence was signed in July 1776, the statue of King George III at Manhattan’s Bowling Green was toppled — by troops under the command of Washington, who was then quartered in New York.

So, there’s an irony to wanting to preserve statues of men who tore down statues.

But a final word of caution. Taking down statues alone doesn’t change anything in the social order. We could be placated with such cosmetic changes while the reign of police terror against African Americans continues, the Dakota Access Pipeline goes ahead, and all the systemic oppression that is actually represented by those statues remains thoroughly in place.

And there’s a paradoxical risk that once the statues come down, memory of the reasons they were brought down will be forgotten along with them. The discussion the question has stirred is a politically necessary one — and it shouldn’t end with the fall of the monuments.