New York could start regulating its estimated half a million basement apartments by following the model of the Loft Law, which in the 1980s enabled the conversion of old manufacturing buildings for residential use, according to a new report.

A new study by City Comptroller Brad Lander shows a possible pathway to formalize the below-ground units, a year after Hurricane Ida killed 13 people in New York City, 11 of whom drowned in largely unregulated basements in Brooklyn and Queens.

“Hurricane Ida tragically called attention to the precarity of tens of thousands of our neighbors living in basements, but one year later, we’ve done little to address it,” said Lander in a statement.

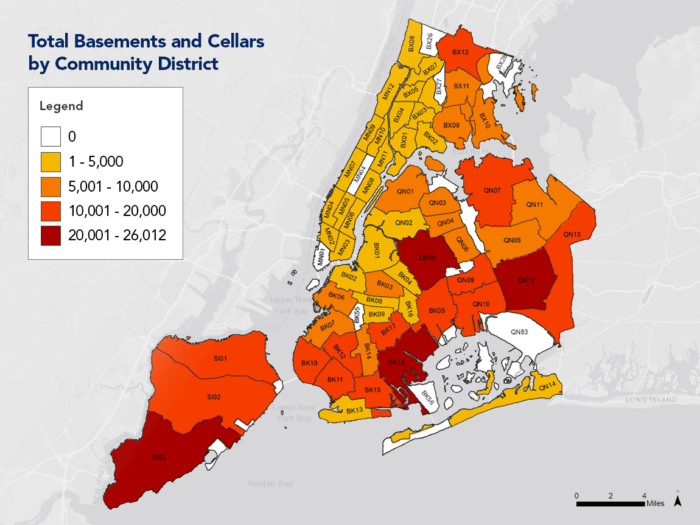

The comptroller’s office estimates there are about 424,800 basement and cellar apartments in one-to-three-family homes across the five boroughs, with the highest concentrations in blue-collar areas like central and eastern Queens and southeast Brooklyn.

One in ten of those, or about 43,000 units, face flood risk right now and by 2050 that number could rise to 136,200 — a third of the underground units — as climate change leads to higher sea levels and more frequent extreme weather.

Tenants have little to no protections since most of these apartments are in an informal rental market.

Under the state law, residential use in buildings with three or more units is allowed in basements, which officials define as apartments whose floor-to-ceiling height is at least half above street level.

For cellars, which are 50% or more below grade, residences are not permitted.

There is no registry for basement apartments, most of whom are illegal, according to Lander’s analysis. Residents, many of whom are low-income, immigrants, and people of color, have few rights, since filing complaints with the city could lead to vacate orders.

They often don’t have other places to live either with housing prices continuing to rise across the Big Apple.

“A full year after Hurricane Ida, it is long overdue to require property owners to install basic safety measures that would prevent further deaths in some of our most vulnerable and at-risk communities. Basement dwellers shouldn’t need to choose between staying quiet about unsafe conditions or risking a vacate order,” said Cea Weaver, an organizer with the advocacy group Housing Justice For All.

The city in 2019 launched a pilot program in eastern Brooklyn to give owners loans to bring their units up to code, but that initiative faltered after former Mayor Bill de Blasio slashed its funding during COVID-19 budget cuts.

Lander’s office proposes to look further back in the city’s history to the 1960s, when people began moving into empty commercial buildings Lower Manhattan amid the decline of manufacturing in areas like SoHo.

The Albany state legislature in 1982 enacted the Loft Law to give these residents some immediate protections as lawmakers forged a path to make them permanently legal to live in. Tenants were protected from evictions and got rights to essential services, along with rent-regulated leases.

Politicians should give underground residents similar interim safeguards as lawmakers come up with a more permanent solution for the opaque underground rental market.

“Living without tenant protections means basement residents are constantly at risk of eviction without due process,” Lander’s statement continued. “We should act now to extend basement residents’ basic rights and responsibilities as well as require and aid owners to make lifesaving improvements.”

He proposed a so-called “basement resident protection law.”

The scheme would create a “basement board” to oversee and administer a program requiring owners to register all currently occupied cellar and basement units and developing inspection regimes.

The law would mandate the installation of basic safety measures like smoke and carbon monoxide detectors and backflow preventers, while enshrining basic rights and responsibilities for tenants and owners, such as eviction protections and entitlement to basic services.

For those living in units that are deemed too unsafe to stay in, the city and state should provide affordable housing, according to the report.