BY PAUL SCHINDLER | A new report from State Comptroller Thomas P. DiNapoli credits the Metropolitan Transportation Authority — which oversees the subway system, Metro North and Long Island Rail Roads, and a number of bridges and tunnels — with having improved both “its financial position for the future” and “customer amenities, service, maintenance, and security” throughout the system.

The clear implication of DiNapoli’s findings are that subway riders — daily confronting trains that are carrying 77 percent more passengers than they were 25 years ago — have a right to expect the MTA to think carefully about whether anticipated fare increases of four percent in 2017 and another four percent in 2019 are, in fact, necessary and appropriate.

Even though it’s staggering to think that a subway system more than a century old increased annual ridership from one billion to 1.7 billion since 1991, the daily push and shove we all experience — especially during rush hour, but often at other times of day, as well — make that statistic all too believable.

EXPRESS OURSELVES

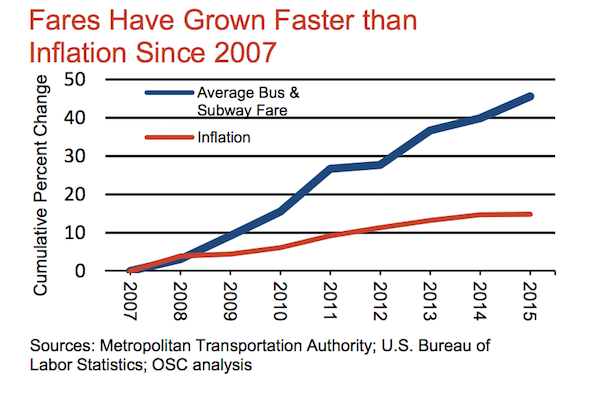

The crowded trains are often an unpleasant nuisance, but what is more galling is that over the past eight years, average subway fares have risen 45 percent — three times the rate of inflation and six times the increase in average salaries in the city, according to DiNapoli.

Which means that each of us is stretching our wallet ever-thinner to board ever-more-crowded subway cars — more congested than at any time since 1949 — as we go to work and back home each day. If the two future fare increases go into effect as currently anticipated, subway fares will have shot up 53 percent between 2007 and 2019.

Which means that each of us is stretching our wallet ever-thinner to board ever-more-crowded subway cars — more congested than at any time since 1949 — as we go to work and back home each day. If the two future fare increases go into effect as currently anticipated, subway fares will have shot up 53 percent between 2007 and 2019.

DiNapoli suggests this need not be.

Over the past six months, the MTA has realized $1.6 billion in unanticipated resources, according to the comptroller’s report, about two-thirds of that due to lower than projected debt service and energy costs. The current fiscal year is now expected to end with $200 million in cash on hand, and projected budget gaps have been closed through 2019. On the capital funding side, after protracted wrangling, the state and city late last year finally agreed on their respective contributions to the MTA’s $29.5 billion building program through 2019.

Alluding to the authority’s stronger financial picture and the fact that subway increases came on the heels of the nation’s Great Recession, DiNapoli rightly concluded, “Because fares have soared in recent years, a time when many riders could least afford the hikes, the MTA should look for ways to minimize future increases.”

In its response to that recommendation, the MTA noted that the two rounds of four-percent increases are merely “forecasts” that have not yet been approved. But an authority spokesperson added that those projected increases are lower than anticipated rates of inflation and also lower than those of past years.

That misses the point.

During a difficult economic period — for both the MTA and its riders — it was the riders who picked up the slack, paying significantly higher fares and showing greater loyalty to the system through their increased use of subways.

Now that things are looking up, the subways’ cramped riders deserve a break.