The 82-year-old woman from Ridgewood, Queens came to Wyckoff Heights Medical Center, just across the Brooklyn/Queens border, on March 3, 2020 with breathing difficulty. She had emphysema, and shortness of breath isn’t unusual among patients with the lung disease that typically affects smokers.

Shortness of breath, however, is also one of the more common symptoms of COVID-19 — and the woman’s underlying condition made her particularly vulnerable to a virus that tends to attack the lungs and induce serious, even fatal, cases of pneumonia and lung scarring.

Sure enough, she tested positive. Her condition was critical, and only deteriorated further.

A team of emergency medical technicians, nurses and doctors tended to the woman and did the best they could to treat her — while simultaneously exposing themselves to a contagion for which there was no known cure, treatment or vaccine, up to that point.

Sadly, their efforts were not enough to save her; she died on March 13 — becoming the first New York City resident to officially succumb to COVID-19.

Close to 30,000 more New Yorkers would suffer a similar fate in the year that followed.

Less than a month after it suffered the first COVID-19 death in New York City, in early April, photographers outside Wyckoff Heights Medical Center captured images that showed just how badly the pandemic had struck the hospital, and others like it across the city.

All day and night, hospital workers in hazmat gear pushed gurneys carrying the bagged bodies of COVID-19 victims from the hospital, transporting them to several refrigerated trucks parked just outside the emergency room, along Stanhope Street. The hospital’s morgue overflowed with dead patients to the point that these trailers served as temporary morgues to store the bodies until funeral directors could come to claim them on the families’ behalf.

The situation wasn’t unique to Wyckoff Hospital. Just about every medical center in New York, by the week of April 12, had one or several of these trailers-turned-temporary morgues parked outside.

Every day, at the height of the crisis, Governor Andrew Cuomo and Mayor Bill de Blasio reported the statistics about COVID-19 — how many were sick, how many tested positive, how many were dead, and so on.

But nothing could better demonstrate the horrific toll COVID-19 reaped on New York City between late March and early April than the sight of those trailers — and the realization that so many families were in mourning, and fear.

The struggle to survive

As ordinary life ceased across New York City with shutdown and social distancing orders in place, hospital rooms were filling up with sick patients. Senior citizens 75 years of age and older suffered the worst, and comprised most of the fatalities — but the virus also targeted younger patients with compromised immune symptoms or pre-existing conditions such as cancer, heart disease or diabetes.

COVID-19 also wound up hitting Black and Latino New Yorkers harder than other communities across the city — exposing tremendous inequities in the health care system that were long ignored. As this reality emerged, public officials on the city and state level worked to expand resources such as COVID-19 testing to help better detect and treat patients who became ill.

To a person, however, no two COVID-19 cases seemed to be the same.

Some who contracted COVID-19 never developed a symptom; most suffered a case of fever, chills, fatigue, loss of taste and/or smell, aches and congestion that dissipated after a few days. A number of people, called “long-haulers,” wound up suffering the ill-effects of COVID-19 for weeks, even months, after the infection ended.

But far too many got such a severe case that it required more robust medical care that only hospitalization could provide.

Though most people recovered and went home, too many who went to the hospital did not improve, regardless of whatever therapeutic treatments the staff provided. That forced doctors to put many of the most severely sick patients on a ventilator — the survival rate once someone was intubated was just 11%.

As COVID-19 spread like fire across New York City during March and April, hospitals across the five boroughs could not keep up with the demand. Despite the best preparations made to free up hospital space and open up additional beds, they quickly filled up. Doctors, nurses and other members of the hospital staff were strained and tested like never before.

Medical workers also exhausted their PPE and other supplies quickly. They were running out of available ventilators to treat patients in intensive care.

Cuomo and de Blasio appealed for aid from the federal government — which was painfully slow to arrive under the Trump administration. Then-President Trump had initially denied the severity of COVID-19, and once it hit New York, he was not quick to assist his former home state. Things would improve in April when Trump dispatched a naval hospital ship to the city and provided additional resources.

The city and state, like many others across the United States, had to fend for themselves — competing with the rest of the world to procure masks, PPE and other supplies for frontline hospital workers. New York state’s government scrambled to find ventilators for dying patients wherever they could.

The lack of supplies bore tragic results as hospital workers treating COVID-19 patients came down with the virus themselves. Many of them would not survive the next month.

The deadly peak

Meanwhile, the crisis continued to deepen, along with the heartbreak.

By late March, the sounds of silence in a stilled New York were cut, almost without end, with the sounds of sirens — as ambulances, fire engines and police vehicles raced to the homes of sick COVID-19 patients and transported them to medical facilities.

The daily death toll began to grow on an exponential scale. Twenty-seven people died of COVID-19 on March 21, and the number rose almost every day there after for the next three weeks.

On March 31, 417 people died of COVID-19.

Then came April 2020 — by far the deadliest month of the pandemic. New York transformed into the epicenter of the global health crisis almost overnight.

The peak of the outbreak occurred over a nine-day stretch between April 7-15. In those nine days, approximately 8,788 New Yorkers died of COVID-19, according to The New York Times; the daily death rate for that period averaged out to 976.

In those nine days, the Empire State had suffered more than three times the number of deaths that resulted from the Sept. 11, 2001 terrorist attacks.

Health care workers and other frontline essential workers suffered mightily. EMS units were stretched thin, with many of the rank and file also getting sick. At one point, between March 31 and April 24, the FDNY had instituted an order limiting resuscitation efforts by EMS units for cardiac arrests victims at home due to the thinning staff and filled hospitals.

The NYPD, on April 6, had 20% of its entire workforce out sick due to COVID-19; the department lost more than four dozen of its staff to the virus, including its Chief of Transportation.

Scores of MTA workers also became sick and died of COVID-19 while their colleagues continued running the transit system at full tilt — even with subway ridership down 90% at the time — just to keep essential workers moving.

New York had never faced such darkness. But glimmers of hope would soon shine through.

To the rescue

The severity of the COVID-19 pandemic in New York, however, brought out the best in the American people.

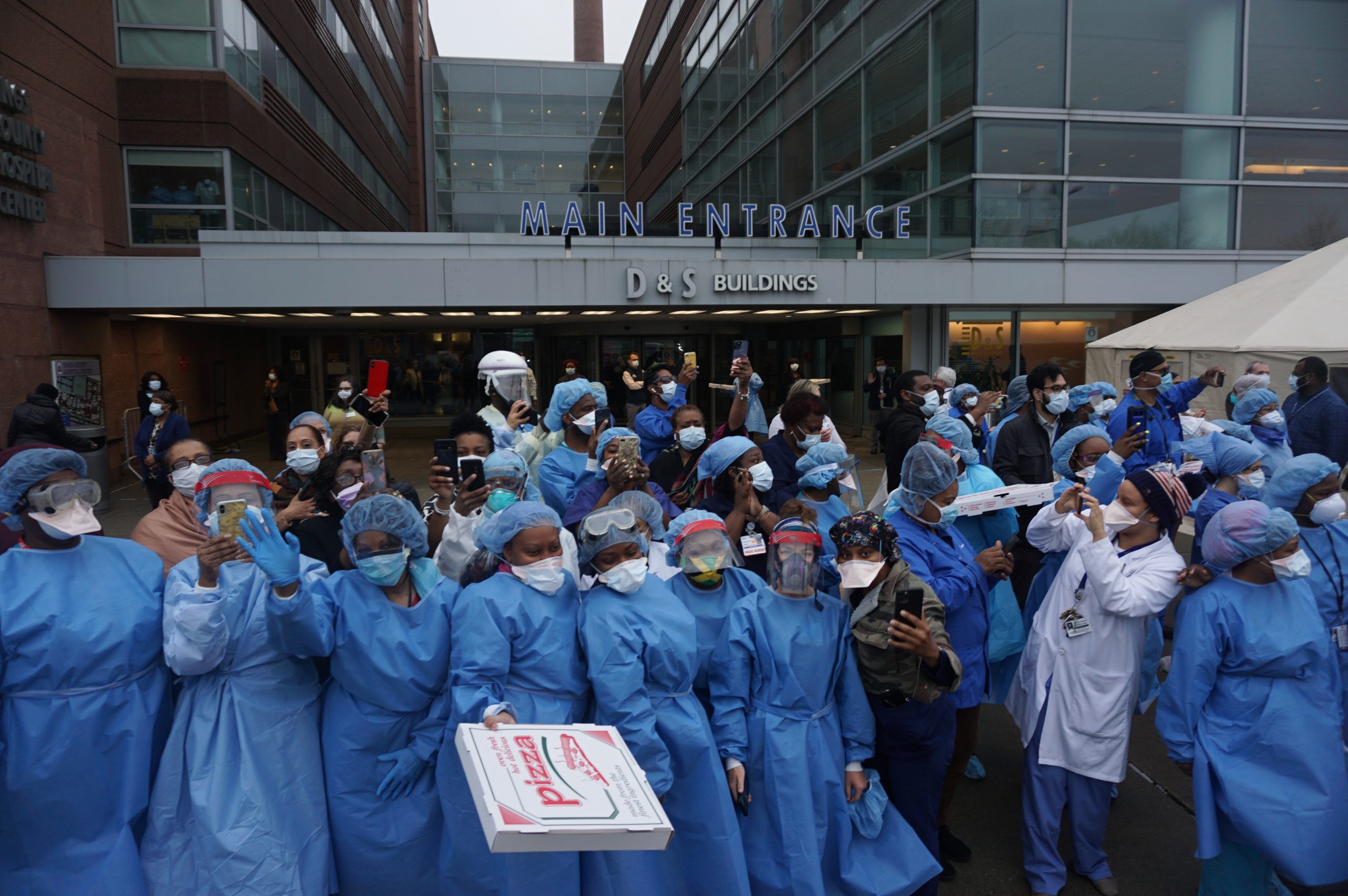

Teams of medical workers voluntarily came to New York City to help the overwhelmed hospitals. That included a convoy of ambulances and emergency medical technicians from every corner of the country that drove into the city to help exhausted EMS crews.

Then came the Navy. On March 31, the USNS Comfort — a floating hospital that last visited New York following the 9/11 attacks — rolled into New York Harbor and docked on the West Side, in the shadow of the Intrepid Sea Air and Space Museum. Their medical staff and supplies proved more valuable than the ship’s hospital bed space in helping the city cope with the tragic pandemic.

Help came from all directions, even when it wasn’t necessarily welcome by everyone. Samaritan’s Purse, a Christian charity founded by the Reverend Franklin Graham, established a field hospital in Central Park, working in coordination with Mount Sinai Hospital.

Despite the assistance the field hospital provided, a number of New Yorkers questioned its presence because of Graham’s personal politics in opposition to LGBTQ rights and support of then-President Trump.

When the federal government could not quickly answer New York’s call for medical supplies, city residents themselves stepped up to answer. Cottage industries popped up overnight across the five boroughs, as small businesses hastily converted their operations to produce masks, face shields and PPE for medical workers desperately in need.

And amid the grief and strife came a heartening ritual that sounded across the entire city every evening at 7 p.m.

Adopting a hastily-formed custom from virus-stricken Europe, New Yorkers belted out a nightly salute to the army of frontline health care workers fighting to keep the city alive. They clanged pots and pans, applauded, cheered, hollered and shouted honors to the doctors, nurses, lab technicians and others putting their own lives at risk to save those most affected by the virus.

The nightly salute doubled as a sign that the city, though silent and grief-stricken, was alive — that there would be a recovery to come down the road — and that the people were determined to overcome the pandemic.

The city worked together to flatten the curve. Throughout May, the infection rate and deaths began to drop slowly, but steadily.

The dark spring began to brighten — and as June approached, thoughts turned to reopening the city’s society, one piece at a time.