The following is a summary of some recent studies on COVID-19. They include research that warrants further study to corroborate the findings and that has yet to be certified by peer review.

COVID-related diabetes may be temporary

Patients with severe COVID-19 who develop diabetes while hospitalized may have only a temporary form of the disease and their blood sugar levels may return to normal afterward, according to new findings.

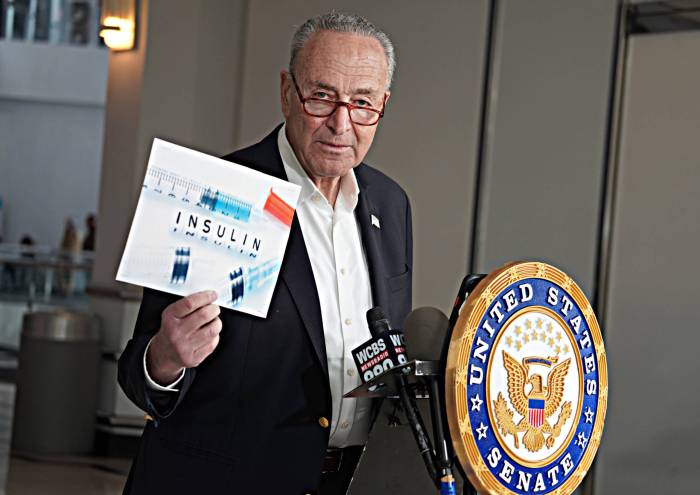

Researchers studied 594 patients who showed signs of diabetes while hospitalized for COVID-19, including 78 with no previous diagnosis of diabetes. Compared to patients with pre-existing diabetes, many of the newly diagnosed patients had less severe blood sugar issues but more serious COVID-19. Roughly a year after leaving the hospital, 40% of the newly diagnosed patients had gone back to blood sugar levels below the cutoff for diabetes, researchers reported in the Journal of Diabetes and Its Complications. “This suggests to us that newly diagnosed diabetes may be a transitory condition related to the acute stress of COVID-19 infection,” study coauthor Dr. Sara Cromer of the Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston said in a statement.

“Our results suggest that … insulin deficiency, if it occurs at all, is generally not permanent,” Cromer said. “These patients may only need insulin or other medications for a short time, and it’s therefore critical that physicians closely follow them to see if and when their conditions improve.”

COVID-19 racial disparities widen with Omicron

New data illustrate the jumps in U.S. coronavirus infection rates caused by the Omicron variant and the heavier toll it has taken on minorities in the latest example of racial disparity in the pandemic.

Overall, for every 2,000 people in the United States, roughly one per day caught a first-time infection when the Delta variant was dominant, compared to about 8 to 10 per day in January after Omicron took over, researchers found. Racial disparities further widened with Omicron, the researchers reported on Tuesday on medRxiv ahead of peer review. During the Delta period, the infection rate in Black patients was 1.3 to 1.4 times higher than for white patients. With Omicron, it jumped to 3 to 4 times higher. The Delta infection rate of 1.6 to 1.8 times higher in Hispanics versus non-Hispanics grew to 3 times higher with Omicron. Children were also hit hard by Omicron infections. The rate in January was highest in children under age 5, at 22 a day per 2,000 in that age-group.

The findings were drawn from 733,509 Delta infections and 147,964 Omicron cases. Omicron was associated with significantly lower rates of emergency department visits, hospitalizations, intensive care unit admissions, and need for mechanical ventilation. However, emergency department visits and need for intensive care was higher among Blacks and Hispanics. The researchers noted that the study subjects might not be representative of all U.S. patients.

Cancer treatments do not impair COVID-19 survival

Powerful cancer therapies do not increase the risk of death for cancer patients with COVID-19, according to research based on data from the UK Coronavirus Cancer Monitoring Project.

Researchers looked at 2,515 adults with COVID-19 who were receiving – or had recently received – systemic cancer treatments such as chemotherapy, immunotherapy, hormonal therapy, or certain targeted drugs. Within a week after COVID-19 diagnosis, 38% of the patients had died. Half the patients in the study were older than 72. Overall, patients with lung cancer or blood cancers were at higher risk for death. Chemotherapy, however, did not affect patients’ risk of death from the virus, and immunotherapy actually improved the odds of survival, according to a report published on Monday in JAMA Network Open.

Earlier studies of COVID-19 patients have found that those with cancer have poorer outcomes, but that may be due to “age, sex, comorbidities, and cancer subtype rather than anticancer treatments,” the research team concluded.