While deaths of incarcerated people, violent conditions for inmates and staff and management problems at Rikers Island have only increased since the pandemic, so have the obstacles to executing the city’s five-year plan to replace the complex with borough-based jails.

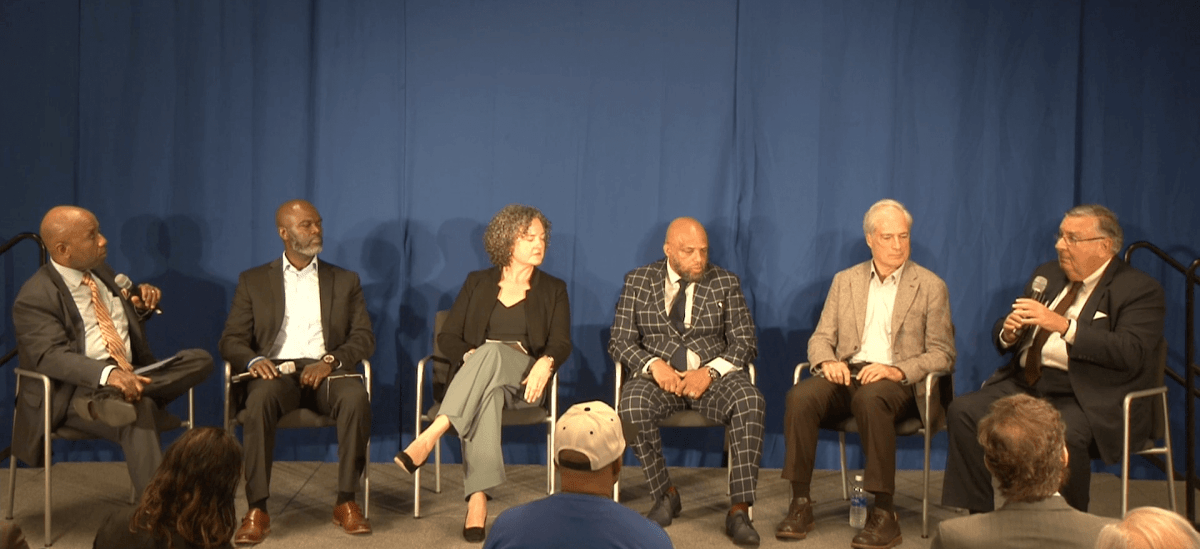

For that reason, the Independent Commission on New York City Criminal Justice and Incarceration Reform and John Jay College partnered to hold a half-day symposium on Wednesday assessing the status of the plan to close the Rikers Island jails and to talk about solutions.

Though the $8 billion borough-based jail project is on schedule, challenges are many and varied, ranging from increasing jail population that the commission argues is artificially inflated, inflationary construction costs and the need for stronger management and oversight from the Department of Corrections.

Proposed solutions include speeding up the COVID- backlog of detainees awaiting trials and funding and creating opportunities to divert people who need mental health treatment to receive city services before they end up in Rikers.

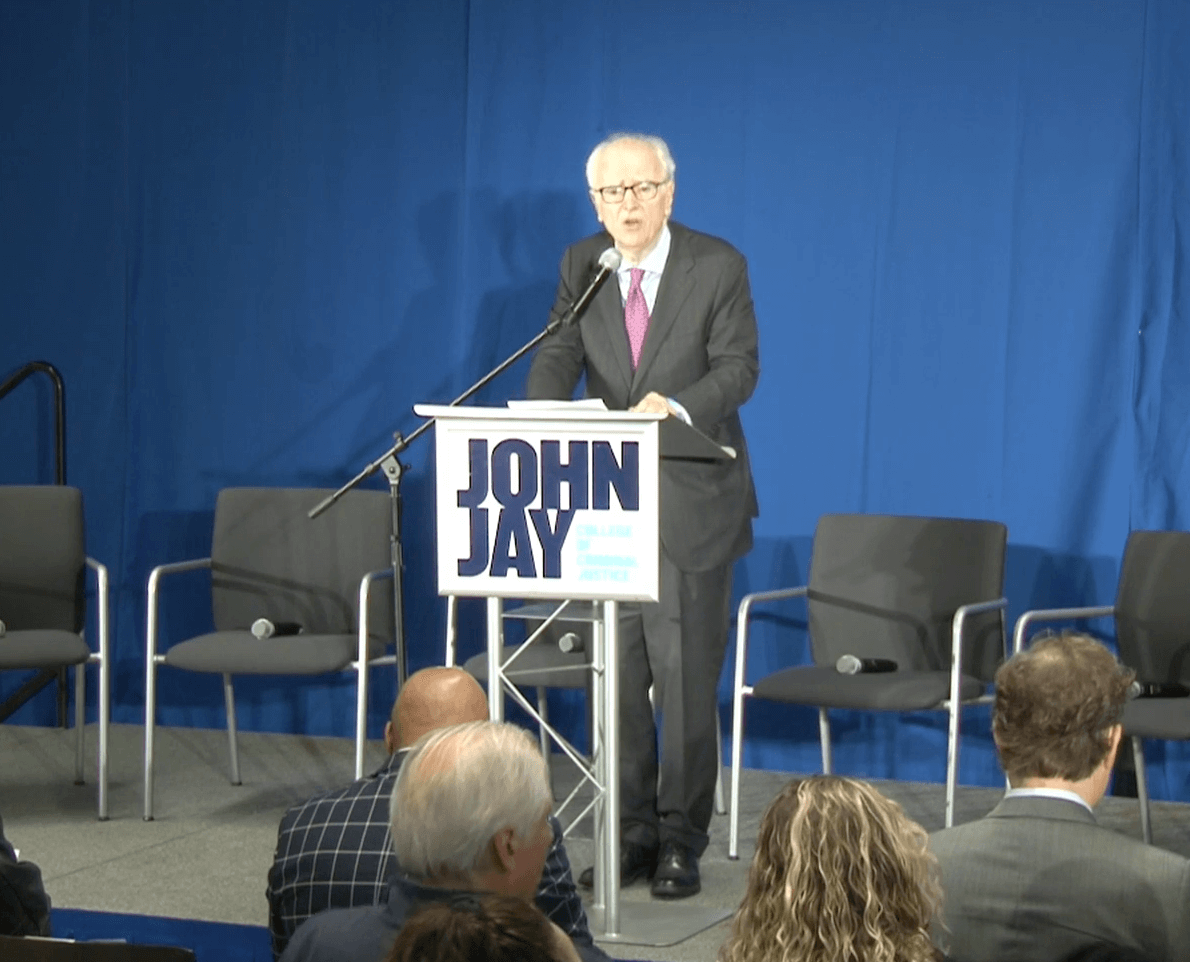

Judge Jonathan Lippman, former Chief Judge of the state and chair of the commission, started out the conference with a central theme: the violence and dysfunction of Rikers ripples out to affect the rest of the city. Therefore, detaining more people awaiting trial actually makes the city less safe, he maintained.

“Gang disputes inside lead directly to violence in our neighborhoods. People who are destabilized and traumatized, return home to our communities. This is not fixable. Rikers is not redeemable. It must for the sake of our city and the values we live by be closed,” he said.

To comply with the new plan, the city’s jail population needs to go down. The new borough-based jails program is designed to handle about 3,500. The city was coming close to that figure pre-pandemic with a population dipping to 3,809 in April 2020, but it has shot up to 5,861 as of Oct. 20, 2022.

“This is not about opening the gates. It is about things like ensuring people actually get a speedy trial and that people with serious mental illness get treatment, not Rikers,” said Judge Lippman.

Of the people in city jails, 51 percent have received mental health services. Speakers said that immediate access for supportive housing and community-based mental health treatment would play a major role in ensuring that this population doesn’t remain in jail, either pre-trial.

The commission has also lobbied for increasing judicial, prosecutorial and defender resources to shrink the length of pre-trial detention, which has increased by 25 days more on average since the pandemic. It has suggested prosecutors do more to assess whether bail is unwarranted, encouraged use of supervised release to defend against cases of flight risk and promoted the city’s pretrial release assessment which evaluates the likelihood that an individual will return to court appearances.

“I think one place where we all need to do a better job is to better explain why keeping people out of the system actually increases our safety. That’s counterintuitive, but it’s factual,” said Richard Aborn of the Citizens Crime Commission of New York City.

The other topic the Commision weighed in on was cost. It estimates that inflation will drive up the $8 billion construction cost estimate of the new borough-based jails by around 20 percent, but the new facility will still save the city money on an annual basis. The jails will be paid for with bonds — money the city borrows and pay back slowly over 30 years. The Commission’s inflation-adjusted estimate is that the jail will cost $660 million per year in bond payments — a figure that is overshadowed by the estimated $2 billion the city is expected to save on the cost of operating Rikers as it is now.

On the topic of the role that Corrections officers have in improving the conditions at Rikers, panelists recommended that the city needs to rethink how it trains and hires for those positions.

Corrections Deputy Warden John Gallagher said that the city needs to think of corrections officers less as police officers and more as social workers. In other words, it needs to attract more sociology majors.

“That’s a people-person job. And that’s the real disconnect. When I think they try to compare us to PD and stuff, a cop sees a dude for eight hours, I see ’em for eight months,” Gallagher said.

One proposal the commission made in that direction is to build a new training academy for correction officers at a cost of $270 million — or $18 million per year in annual debt service costs.