BY NATHAN RILEY | Despite the fact that Democrats continue to become more dependent on reliable voting support from communities of color, groups fighting the criminalization of marginalized New Yorkers report that under Mayor Bill de Blasio virtually everyone arrested for marijuana is black or Latino.

Appearing at a July 11 City Hall press conference, drug reformers were joined by advocates for communities and youth of color in demanding that the city’s five district attorneys refuse to prosecute any arrests for marijuana in public view as the fruits of “Jim Crow” enforcement.

In 2016, such arrests were up 10 percent and totaled 18,121 — roughly 350 every week. Seventy-six percent of those arrested had never been convicted of even a single misdemeanor, but the police pressed charges anyway.

Critics charge despite mayor’s 2013 campaign rhetoric, enforcement still racially skewed

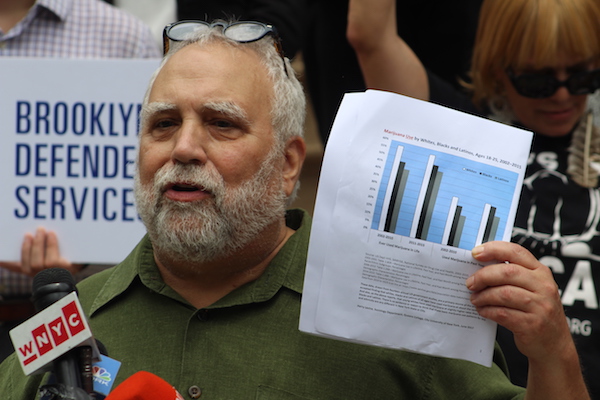

Advocates — including representatives from the Drug Policy Alliance, LatinoJustice PRLDEF, and the Brooklyn Defenders, a legal aid group — presented academic research showing that marijuana arrests under de Blasio “have the same overwhelming racial disparities as under Bloomberg.”

Per 100,000 population, the rate of arrest in Harlem’s 30th precinct was 1,116, but in the predominantly white and well-heeled Upper West Side 20th precinct it was 50. In East Harlem’s 25th precinct, it was 1,038 per 100,000, a sharp contrast with the posh Park Avenue 19th precinct that had a rate of just 6.

The state director of the Drug Policy Alliance, Kassandra Frederique, referred to these disparities as “staggering.”

Even after a federal court order curbed the stop and frisk program, which reached astronomical highs in the Bloomberg years, racially skewed enforcement has continued. Last year, 85 percent of the arrestees were black or Latino. During de Blasio’s first three years as mayor, 60,000 arrests were made for marijuana in public view. The grand total in 20 years of discriminatory enforcement is 700,000 arrests, Frederique said.

Queens College Professor Harry Levine, the sociologist who broke the arrest statistics down by precincts, was unsparing in his criticism.

“It’s essentially Jim Crow police enforcement,” he said. “One set of laws for white people, one set of laws for people of color.”

In 2013, while campaigning for his first term, the mayor acknowledged that “low-level marijuana arrests have disastrous consequences” and there is a “clear racial bias” in these arrests.

“This policy is unjust and wrong,” de Blasio said at the time.

The news conference damned him for breaking his promise that things would change.

Scott Hechinger, the director of policy at the Brooklyn Defenders, accused the district attorneys from the five boroughs of “insulating the NYPD from being scrutinized for bad stops. Prosecutors don’t care about marijuana arrests,” so they allow defendants to walk, but only after they find their way into the court system. He slammed this result as a “wholly inadequate response,” resulting in cops continuing their disparate enforcement because the DAs are not really taking them on. The system operates on autopilot, Hechinger charged.

In a famous 2013 court decision holding that the NYPD’s stop and frisk practices relied on unconstitutional searches, US District Judge Shira A. Scheindlin condemned city officials for adopting “an attitude of willful blindness” toward racial disparities. Hechinger called on the district attorneys to confront the police arrests head-on, using prosecutorial discretion to dismiss the charges right at the precincts to send a clear message that deliberate indifference toward racist enforcement is not acceptable.

The statistics presented by Levine understate the impact of these current policies. Arrests are concentrated on those under 34, who are handcuffed, put in police cars, and taken to the precinct where their fingerprints enter the system for review by law enforcement and immigration officials. Hechinger scornfully dismissed the desk appearance tickets offered by police as “sham protections.” Once collared, a person spends up to 12 hours in the precinct and is then told to go to court two or three weeks later. If their prints trigger an immigration hold from the federal Immigration and Customs Enforcement, ICE agents have a specific time and place to serve a warrant.

Hechinger was equally critical of cops writing summonses, tickets issued after they are shown identification. Those who can afford it simply pay the ticket, while those who can’t ignore the summons and a criminal warrant is automatically issued. They then get arrested the next time they are stopped. The system has undergone no fundamental reform, he argued.

In his report, “Unjust and Unconstitutional: 60,000 Jim Crow Marijuana Arrests in Mayor de Blasio’s New York,” Levine writes that the NYPD has “never offered any serious defense of the arrests.”

Levine’s reported noted that even Heather Mac Donald, a conservative commentator affiliated with the Manhattan Institute who is a defender of tough broken windows policing, has questioned the NYPD’s marijuana enforcement, arguing that the time officers spend in court reduces “patrol presence” on the streets.

The continued pattern of arrests under “reformer” de Blasio speaks to the policy’s worrisome intractability. Even though the policy has been thoroughly discredited, the arrests continue. As long as the police are allowed to make arrests, they will haul in the most powerless New Yorkers.

The real solution, reformers agree, is taking away the power of police to make arrests by taxing and regulating pot under legislation introduced by Manhattan’s East Side State Senator Liz Kruger and Buffalo Assemblymember Crystal Peoples-Stokes. Their legislation, however, languishes under Governor Andrew Cuomo, who is reticent even on medical marijuana, straightjacketing that program so much that it doesn’t permit veterans suffering from PTSD to buy smokable herb.

Advocates support the Colorado solution.

“A marijuana revolution” said Juan Cartagena, president and general counsel of LatinoJustice PRLDEF, is “just, it’s rational, and it’s time.”