By Rachel Holliday Smith, THE CITY

This article was originally published on by THE CITY

East Harlem escaped Superstorm Sandy relatively unscathed because of luck, timing — and the moon.

Had the tides been slightly different when the storm hit in October of 2012, the low-lying neighborhood would have been inundated, according to flood researchers. Just a six-hour shift, a recent analysis confirms, would have brought fast-moving water in with the tide.

The risks to East Harlem are no secret to city officials — or locals who say their streets regularly flood in strong rain. In 2017, City Hall set out to study how best to protect the area.

With $1 million in hand from the federal government, the city hired consultants in 2017 to create a 280-page “vision plan” for how to make East Harlem resilient to climate change, according to press releases and project proposal documents.

Multiple design firms were hired to study vulnerabilities and risk, assess the feasibility of an “integrated flood protection system” and estimate the cost, among other objectives, the proposal document says.

The report was completed in 2018. What’s in it, however, is still a mystery.

The city Department of Parks and Recreation, the agency overseeing the report with the Mayor’s Office of Resiliency, has released only a 25-page summary of the full plan.

Buried Underwater

When George Janes, a land use expert and consultant for East Harlem’s community board, requested the full document through the Freedom of Information Law, he got a copy — with nearly every page blacked out by redactions, including the table of contents.

“They shitcanned the work,” he told THE CITY.

Janes appealed to try to get an unredacted copy, but lawyers for the Parks Department shot him down, saying the 280-page report is “a non-final, pre-decisional record containing consultant ideas and recommendations that may be modified or rejected” and, therefore, is not subject to Freedom of Information Law requirements.

Mayor’s Office of Recovery & Resiliency

Mayor’s Office of Recovery & ResiliencyManhattan Borough President Gale Brewer sent a letter to Parks Commissioner Mitchell Silver on Christmas Eve on behalf of Manhattan Community Board 11, urging him to release the report.

Phil Ortiz, a spokesperson for the Mayor’s Office of Resiliency who responded to THE CITY on behalf of the Parks Department, reiterated what the agency said in its reply to Janes’ appeal — that “draft materials” are not subject to open records requests. He added that the report offered “valuable insight into current and future risks of this neighborhood.”

The report assisted the city to successfully apply for a FEMA grant that will help “explore the feasibility of a stormwater management project at NYCHA’s Clinton Houses,” he said.

He added that the unreleased plan is also influencing the Parks Department and the city Economic Development Corporation’s planning for a new waterfront park from East 125th Street to East 132nd Street, which aims to “elevate the park for sea level rise without exacerbating interior drainage challenges.”

“The ‘Vision Plan for a Resilient East Harlem’ will continue to inform the city’s multi-hazard approach to climate adaptation in this area and will help the city seek new funding sources for future investments to address flooding and extreme heat,” he said in the statement.

But to Marie Winfield, an East Harlemite and former CB11 member who has tracked infrastructure projects in the neighborhood for years, the lack of transparency makes it nearly impossible for locals to make sure the area is protected.

“If we don’t have the recommendations — they won’t let us see the recommendations, but the studies were done — then how can the community advocate for what is sorely needed?” asked Winfield, who is legal director of the Fair Housing Justice Center.

‘Even When It Just Rains’

The de Blasio administration first identified East Harlem as in need of an integrated flood protection system in its 2014 resiliency progress report.

Large swaths of the neighborhood sit squarely in a high-risk flood zone, according to flood maps from the Federal Emergency Management Agency. The most at-risk areas are along First Avenue from East 93rd Street to the Willis Avenue Bridge and inward adjacent to East 106th Street nearly to Central Park.

Pilar DeJesus doesn’t need to read the city’s resiliency report to know her neighborhood is at risk of flooding. DeJesus lives at the corner of East 107th Street and Third Avenue, smack in the middle of the high-risk part of the FEMA maps.

“I walk around often and I’ve noticed the massive flooding, even when it just rains,” she said.

Standing water appears on roads and sidewalks often, she said. The bike lane on First Avenue is one big puddle after a rainstorm. The area in front of the Select Bus stop on East 106th Street and Second Avenue is like “a little pond,” she said.

Ben Fractenberg/THE CITY

Ben Fractenberg/THE CITYA strong storm would bring serious problems to the neighborhood, according to Prof. Reza Marsooli of Hoboken’s Stevens Institute, who studies flood hazards and risk.

He co-authored a study published in September based on a year-long modeling of the tides’ effect on Manhattan during Sandy. His team’s research found that if the storm had arrived as little as six hours earlier, the tide within the western edge of the Long Island Sound would have carried the river water straight into East Harlem.

“The storm surge would have been much worse and the water velocity would have been much higher,” he told THE CITY.

Though Marsooli’s research is the latest update on tide modeling, the insight is not new. Colleagues of his published similar findings in 2014 — in a study co-authored with Daniel Zarrilli, the current top advisor to Mayor Bill de Blasio on resiliency issues.

The city also acknowledged the near-miss in East Harlem during Sandy in its 2017 request for proposals seeking a consultant to produce the unreleased resiliency “vision plan.”

“When Hurricane Sandy hit the city on October 29, 2012, East Harlem was spared the full force of the storm that hit the area around western Long Island Sound almost exactly at low tide, meaning that East Harlem, Northern Queens and parts of the Bronx were not as badly affected as they could have been,” the proposal read.

More than the redactions, what upsets Janes is the lack of attention for a neighborhood at serious risk.

“The city is spending hundreds of millions, billions of dollars on resiliency efforts right now, right along the Brooklyn waterfront, right in Lower Manhattan. We have the East Side Coastal Resiliency project — shovels in the ground, right now,” Janes said, speaking of the effort to rebuild the Lower East Side waterfront. “And what does East Harlem have? Absolutely nothing.”

To DeJesus, keeping the report under wraps makes little sense. A few years ago, she brought her concerns about flooding to a meeting at the DREAM School, a local charter, where city officials held one of several outreach events conducted as part of the “Resilient East Harlem” report.

“Why would you hide this information, especially if it could be information that could possibly help us protect ourselves?” she said. “I was under the impression when I went to that meeting, that that information was going to be public.”

Missed Opportunity

Some descriptions of the 280-page report have trickled out — through the websites of the consultants who put it together.

One Architecture won an award for its work on the “Resilient East Harlem Report,” the firm’s website says. Writer and former city Traffic Commissioner “Gridlock” Sam Schwartz was the transportation lead for the resiliency plan and described it as “one of the most comprehensive in the U.S. to date.”

Schwartz declined to discuss the project. One Architecture did not respond to a request for comment.

No further details from the city have emerged. And while the Parks Department sits on the 280-page report, momentum is building for at least one major project that will undoubtedly be affected by the effects of climate change.

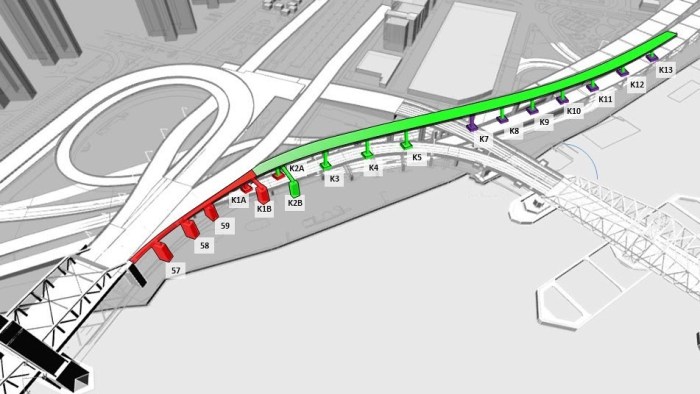

The rejection of Janes’ FOIL appeal came just days before Gov. Andrew Cuomo promised the next phase of the Second Avenue Subway would move forward.

That project will bring new stations along Second Avenue. How underground construction will mesh with the city’s resiliency “vision plan” is unclear. An MTA spokesperson referred THE CITY to the transit authority’s lengthy environmental assessment for the subway project, which was updated after Sandy to account for flood risks.

The document acknowledges that the planned East 106th Street and East 116th Street stations are within FEMA’s 100- and 500-year flood plains, respectively, and would be designed according to updated “flood design standards.”

“Critical electrical and ventilation equipment will be located above the design flood elevation,” the assessment reads. The stations will also include watertight structures and equipment, as well as “flood gates or deployable barriers for station entrances.”

The neighborhood’s community board also recently considered citywide land use changes that aim to make new developments more resistant to flooding and would allow for some retrofitting of existing buildings. But some local infrastructure will need more targeted help.

Winfield points out that East Harlem’s waterfront is crumbling into the East River — literally. Sinkholes have opened up on the East Side Esplanade, Pier 107 has been plagued by maintenance issues and repairs on the waterfront have languished for years.

“You would imagine that the city would take that as an opportunity to fix the infrastructure and do the resiliency planning at the same time,” Winfield said. “I don’t know what will happen when the pier floats into the river.”

THE CITY is an independent, nonprofit news outlet dedicated to hard-hitting reporting that serves the people of New York.