BY LEVAR ALONZO | State Senator Liz Krueger, Citizen Action of New York, the Legal Aid Society, and the Lexington Democratic Club, along with other Upper East Side Democratic clubs, co-sponsored a Sept. 14 forum on the proposal to hold a state constitutional convention. Area residents packed the All Souls Church at 1157 Lexington Ave. in the hopes that their questions and uncertainties about such a convention, on which voters will make a decision in the Nov. 7 general election, would be addressed.

Four panelists were on hand to debate the issue, with the pro side arguing that the New York Constitution must be revised to encourage greater voter turnout and restrain the influence of entrenched political interests, while the con side raised concerns about the threat such a convention could pose for important rights and protections currently enshrined in the Constitution.

“I myself am leaning heavily pro-convention, which puts me in the minority among elected officials,” said Krueger, the East Side senator who moderated the evening. “It doesn’t change the fact that I respect both sides of the argument.”

This November, New Yorkers, for the first time in 20 years, will have a chance to vote yes or no on whether they want to hold a constitutional convention to amend the state’s founding document.

Since 1967, when the last convention was held, voters have repeatedly rejected the idea of holding a convention. The recent volatility in voter behavior, as evidenced by the surprise election of Donald Trump last Novemeber, has many elected officials, advoacy organizations, and voters concerned about the potential for opening up a can of worms with no predictable outcomes should a convention be approved.

In her opening statement, Krueger urged those in attendance to listen and weigh both sides of the issue to make an educated choice come Nov. 7. She specificially disputed social media rumors that choosing not to vote on that ballot question would be an automatic yes.

Non-profit groups like the Legal Aid Society and Planned Parenthood have taken issue with the push for a convention, warning that it could repeal hard-fought protections and also be influenced by “dark money” forces.

Adriene Holder, who serves as the Legal Aid Society’s attorney-in-charge of civil practice pointed to concerns that a constitutional convention could weaken or imperil entirely Article 17, which protects low-income New Yorkers. Article 17, she explained, was added to the State Constitution in a convention called during the Great Depression in 1938 and mandates that the state provide assistance to low-income residents. That provision has been an effective tool used by lawyers in court cases aimed at providing adequate social service supports for New Yorkers in need, according to Holder, who noted that Article 17 has been the target of opponents in earlier conventions and in the Legislature since its enactment.

“If a convention is called, every part of the State Constitution could be subject to replacement or revision,” Holder said. “This includes really the key protection for low-income New Yorkers.”

According to the New York State Library website, when the last constitutional convention was held in in 1967, the proposed amendments that resulted were rejected by voters. The 1938 convention, in contrast, was successful at amending the Constitution, addding safeguards including Article 17.

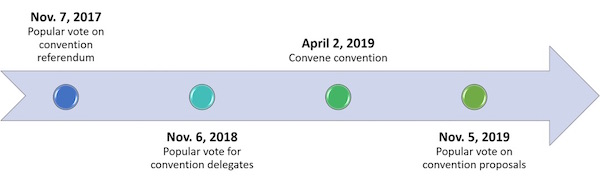

Evan Davis, senior counsel at Cleary Gottlieb and manager of the Committee for a Constitutional Convention, argued that a constitutional convention is really a partnership between the voters and the convention delegates. If voters in November decide to hold a convention, 189 delegates would be elected next year to a 2019 convention that would consider amendments to the exising Constitution. Any amendments the delegates approve would then go back before the public for an up or down vote.

“The individual amendments are put before the people and ultimately the people will have to decide,” Davis said. “That is a very important protection in this whole process.”

In making his case, Davis noted the low voter turnout in last week’s primary elections, where just 14 percent of Democrats — who make up the large majority of city voters — turned out. He argued that because of tough voter registration restrictions written into the Constitution, with deadlines set about a month prior to voting, many residents who only tune in during the final weeks of a campaign are deprived of the chance to vote. Online registration requires a driver’s license or an official non-driver’s ID, but Davis said the fact that half of the city’s adults don’t have a driver’s license — with many not bothering to obtain a non-driver’s ID — imposes a practical barrier to registering in this way.

Just as much as Davis feels that a constitutional convention could fix barriers to effective governing in the State Constitution, some feel that it could still take away important individual rights and safety net protections.

“In a perfect world, Con-Con would be a good idea,” said Robin Chappelle Golston, president and CEO of Planned Parenthood Empire States Acts, adding that its downsides are the “lack of transparency and possible loss of what we already have in the Constitution.”

Planned Parenthood is a leading advocate for women’s reproductive rights.

Chappelle Golston’s concern is that the public will not be able to weigh in on the process until the convention is over, which she warned could be too late. The convention, she said, would likely become an “inside baseball game” with backroom deals being reached by delegates. Her organization, she said, fears that existing protections for abortion could be traded away for changes in other key areas.

The forum also made clear that an underlying tension between upstate and downstate interests is beginning to surface in the debate over holding a convention.

“We live in the New York City bubble and don’t worry much about certain issues, but we have to realize Trump carried 46 of our 62 counties in the state,” Chappelle Golston said. “This would not be a progressive bastion figuring out ways to make our Constitution more progressive. There will be delegates with other agendas and that leads to compromise.”

She also raised concerns about whether the delegates elected would be truly representative of all communities across New York.

“We also believe there won’t be true representation of the people that make up this great state,” Chappelle Golston said.

Bill Samuels, a businessman and founder of Effective NY, a nonpartisan think tank focused on public policy isseus, spoke in favor of a convention, arguing that unwarranted fears should not stand in the way of breaking down traditions that hold the state back.

“Andrew Cuomo and that culture is as old and as outdated as Tammany Hall, and we must change it,” he said.

Then, alluding to the fact that most Albany legislative negotiations are carried out among the governor, Democratic Assembly Speaker Carl Heastie, Republican Senate Majority Leader John Flanagan, and Senator Jeff Klein, a Bronx Democrat who heads up the rump Independent Democratic Conference, but exclude Senator Andrea Stewart-Cousins, who leads the Democrats, who nominally have a majority, he added, “There is no better example than when four men go in a room and they exclude the woman that runs the Democratic Party. Think that’s going to change in 2018?”

Samuels argued that individual legislators need a greater say in Albany and that transparency should be encouraged in contrast to the current practice of closed-door negotiations.

Without spelling out details, Samuels also advocated for a constitutional amendment to create pension benefits for New York’s many freelance and non-union workers — an effort that runs counter to strong economic trends in recent decades.

“Sixty percent of our workers in Manhattan have zero pensions,” he said. “One of my amendments is to require that the Constitution have a pooling access to all workers, so that not only union workers have good pensions but the rest of us do, too.”

In his closing remarks, Samuels encouraged audience members to run to become delegates.

“This will an exciting time, and it will be fun to bring about change,” he said. “I urge you not to have doubt and uncertainty.”

But doubt and uncertainty are what brought many to All Souls Church last week in the first place, and it was unclear at the evening’s conclusion how many of the crowd’s questions had been clarified. Voters now have just seven weeks to become comfortable that they are making an informed decision on Nov. 7.