By Harry Newman

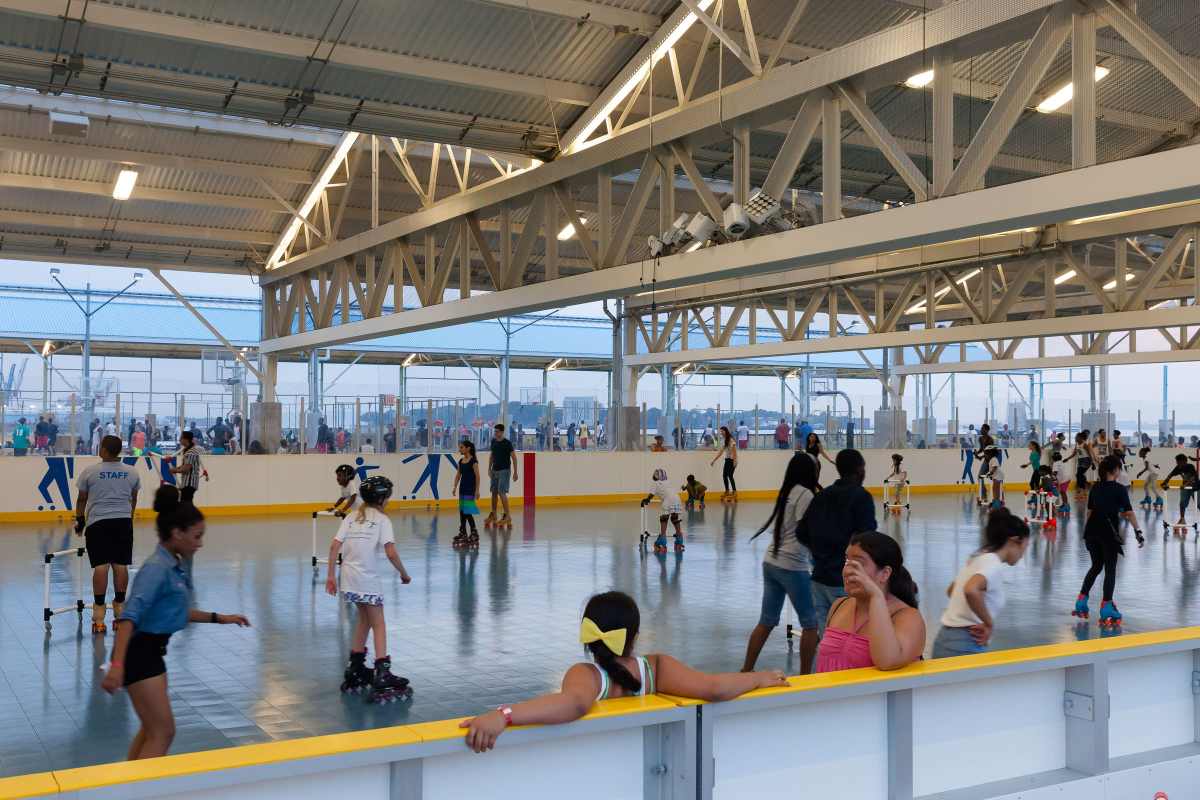

For a small group of dancers and choreographers, the works and ideas of Richard Bull and his wife, Cynthia Novack, are among the most influential and meaningful contributions to modern dance. That circle may be widening through the efforts of Dance New Amsterdam, the new center for dance that opened last year in Lower Manhattan, where a plaque was dedicated to the couple’s memory Monday night.

In dance, music, and words — and usually all three combined — former colleagues, students, and family members of the Bulls (who passed away in the late-1990s) remembered and re-created dances they made with the Richard Bull Dance Theatre, at the Warren Street Performance Loft the two had founded.

There was a “talking dance” for the unveiling of the plaque, in which three performers talked and danced simultaneously, cueing off each others’ words and movements to create variations in tone, intensity and pacing as they welcomed us to the event. There was a “radio dance” where a group of dancers responded to recordings of radio broadcasts, their movements and reactions to each other following the rhythms and patterns of music, news reports, call-in programs and static. There were solos with dancers guided by instructions given to them in writing at the beginning of the piece or verbally through the course of their performance. All were based on the concepts of structured improvisation that Richard Bull and Cynthia Novack pioneered and developed throughout their lives.

“Cynthia and Richard were amazing innovators in dance in the 70s, 80s, and 90s,” Charles Wright, DNA’s Artistic Director and one of its founders, said in his post-unveiling opening remarks. “[They] taught us that dances can be created and experienced in the moment.”

Richard Bull looked at improvisation in a way no one else in dance had before. Trained as a jazz musician, he moved to New York from Detroit in the late-1940s to study with pianist Lennie Tristano and worked as an accompanist at dance schools to support himself. He soon became absorbed with dance and took classes with Alwin Nikolais. By the mid-1950s, he had switched careers—and brought the sensibilities and ideas of jazz, particularly jazz improvisation, with him.

He knew the way musicians could come together without ever having played before and create a fully realized piece of music through their shared understanding of basic compositional ideas and structures. Bull saw in dancers the same possibilities for spontaneous invention in performance and didn’t understand why they couldn’t also come together to create fully realized pieces on the spot with the same complexity and richness as dances composed and rehearsed beforehand.

“Richard found ways to use the traditional ideas of choreography — spatial organization, theme and variation, phrasing, gesture — and make structures from them that were similar to the structures in jazz music,” George Russell, a member of the Bulls’ company in the 1980s, elaborated before the event. “Instead of the material being set, the compositional idea was set and that allowed the performance to be both spontaneous, as improvisation always is, and composed at the same time.”

In the 1960s, Bull began teaching in college dance departments and by the mid-70s had become the head of dance at SUNY-Brockport, where he started working with Cynthia Novack. In Novack, he found the perfect collaborator to take his ideas to their furthest extent. Where Bull had come to dance from the outside, Novack had trained as a dancer and, over time, she created the movement techniques dancers needed to realize his choreographic ideas. In 1978, they moved back to New York City and started the Warren Street Performance Loft in Tribeca, where they worked together for the rest of their lives.

The Warren Street Loft became a center of the dance world in New York and artists would come from all over to attend the performances held there nearly every weekend. Primarily dedicated to the Bulls’ own work, the loft also included presentations of the work of other performers. Among the artists who performed there are Bill T. Jones, Blondell Cummings, Deborah Hay, Brenda Bufalino and dozens of others.

“It was a very hospitable place,” said Susan Foster, the author of “Dances That Describe Themselves: The Improvised Choreography of Richard Bull.” “It was just two rooms, the front part [where Novack and Bull lived] and the back half which was this huge dance space.” To start the performance, dancers had to walk from the front, where the dressing room was, through the audience to the dance floor, often greeting people along the way. “It had a real sense of community. It was always a place where you would see somebody that you knew and could catch up.”

In many ways, Dance New Amsterdam continues the tradition of the Warren Street Performance Loft. Located at Chambers and Broadway, a block and a half from where the loft had been for 17 years, DNA is focused on serving dancers and providing what they need to develop into active, engaged participants in dance making and not just passive executers of others’ ideas. This is the essence of the Bulls’ lifetime of dance and a demonstration of their influence on the form.

The plaque, which reads simply, “In Memory of Richard Bull, Cynthia Jean Cohen Bull (aka Cynthia Novack) and the Warren Street Performance Loft,” will be above the front desk in the main entrance where every dancer signs in to take classes.

The 135-seat theater at Dance New Amsterdam was full beyond capacity for the dedication, with chairs added wherever they could fit. Performers had from come across the country for the event, from contemporaries of the Bulls to company members and students from the 70s and 80s to dancers in their 20s who had studied with the Bulls at the end of their careers in the 90s. Some were meeting for the first time, others meeting for the first time in years. And it seemed — if only for one night — that the Warren Street Performance Loft had come back to life again.