This article was originally published on by THE CITY

Even before the pandemic, many of New York’s houses of worship were facing an existential crisis.

For years, interest in joining churches, mosques and synagogues has been on the decline nationally, leaving the physical homes and finances of many spiritual communities deteriorated. Now, amid the upheaval of the coronavirus, survival is even more uncertain, said Rachel Hildebrandt, senior program manager at Partners for Sacred Places, a nonprofit whose mission is to promote community use of religious real estate.

“Many churches have plateaued,” Hildebrandt said. “There’s just a general uneasiness about the future right now — and I think COVID made it worse.”

A cadre of clergy, congregants, land use experts and planners are fighting back against the trend in one of the places hit hardest by the pandemic with a new handbook — a bible, of sorts.

The “Action Book,” released this week by Manhattan Borough President Gale Brewer, is chock full of answers to the question: How can a congregation keep its building, while still carrying out its mission?

Figuring that out can be incredibly difficult, noted Donna Schaper, senior minister at the Judson Memorial Church in Greenwich Village, which is among the groups whose input is included in Brewer’s report. Congregations are not usually equipped to be a real estate business filled with developers who are “not all rapacious,” she said, but can be.

“There’s just a lot of places that are trying to rip off churches,” she said.

Withstanding the Pressure

Judson founded a nonprofit called Bricks and Mortals that aims to help religious institutions cope with mounting bills and the pressures to sell.

Schaper said she’s found that small churches with fewer than 20 members are most at risk. Many haven’t paid their pastor in months, or have had their water cut, or lights turned off.

“A lot of these congregations just disappear,” Schaper said.

Nationally, about 1% of congregations close each year, according to research cited by The New York Times late last year. Brewer’s office found that between 2010 and 2020, the numbers of religious congregations in Manhattan declined by 7% from 976 to 907.

Karen DiLossi, director of arts at Partners for Sacred Places — which also informed Brewer’s report — said the pressure is worse in Black and brown neighborhoods where would-be buyers target weakened churches.

“They may have a diminishing congregation, and maybe they have a huge facility, but the upkeep is too much,” she said. “They feel tremendous amounts of pressure to sell.”

The Action Book, written in partnership with the NYU Wagner School of Public Service, offers guidance about alternatives to cashing out. The report also explains the basics of New York’s land use rules, how air rights work, the pros and cons of landmarking a building and what to know about redevelopment.

Brewer’s guide gives local examples of how some local congregations have made their properties work for them. It describes a deal made in Harlem by Bethel Gospel Assembly to sell air rights and allow a developer to build on the church’s former parking lot. In Washington Heights, Rocky Mountain Baptist Church arranged to be part of a senior housing development under construction now.

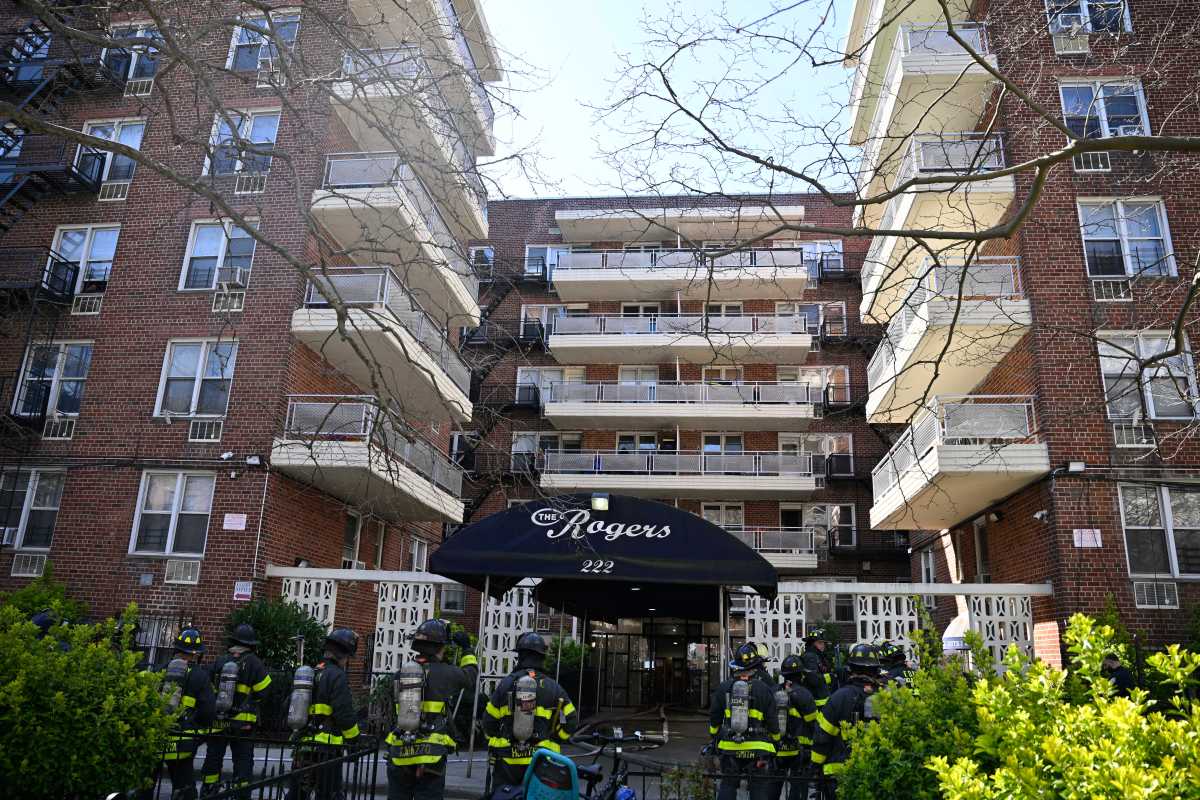

Hiram Alejandro Durán/THE CITY

Hiram Alejandro Durán/THE CITY“Religious institutions are a bedrock of neighborhood life and identity, and serve as a spiritual, social, and cultural resource for our city,” Brewer said in the guide’s introduction. “The pressure of being in New York shouldn’t have to mean that congregations close.”

The Action Book focuses on Manhattan, but is relevant across the city.

In Brooklyn — long-ago nicknamed “the borough of churches,” although many have disappeared amid a building boom — congregations have a lot of options, said Borough President Eric Adams. But they often need guidance and support to navigate a system that is “too bureaucratic and difficult,” he told THE CITY.

Adams, who is running for mayor, offers free land use analysis to houses of worship through his office and has given funding to congregations looking to build affordable housing through his Faith-Based Development Initiative.

“We were surprised to find that many of our houses of worship had no idea of this term called ‘air rights’ — how they could actually build housing that would offset the cost of running their churches,” he said.

The ‘World of Promises’

Sales or development deals involving houses of worship must be approved by state court or the state’s Charities Bureau in the Office of the Attorney General.

An attorney who specializes in faith-based real estate transactions there said congregations should first figure out what they need, what they’ll need in the future and “the value of their property and its potential.”

To do that, she said, it’s imperative they hire “capable, sophisticated, experienced counsel” to “know, know, know the value of what you’re transferring.”

Otherwise, people of faith may be more apt to fall for a scam.

“I call it the world of promises, promises,” she told THE CITY, speaking on condition of anonymity. “You know, ‘I’m going to build you this beautiful Shangri-La for you. It’s going to be worth even more than your property,’ which I always try to tell people — that’s not really how business works. If they’re promising more than it’s worth, that’s a red flag.”

She cautioned that while the attorney general oversees the initial approval of a deal, the state’s religious incorporation law does not mandate the agency follow up and make sure a developer keeps its promises.

In Brooklyn, Adams underscored the need for congregations to find trusted legal help before moving forward.

“You want to make sure that something doesn’t happen inappropriately — that you lose your church,” he said. “It is imperative that you find a legal advisor that is familiar with this type of relationship.”

The Gospel of Flexibility

Some congregations may choose to avoid development, and the Action Book outlines how to make that happen, too. At Judson, the church works hard to get the most out of its existing building. Schaper calls it “hyper-use” — making sure the space is occupied most of the time.

Her advice? “Remove the pews,” she said — to make sanctuary space more flexible for a wide range of events, uses and organizations. Before the pandemic, Judson hosted six different congregations that used space there, as well as a theater group, services for immigrants and more.

DiLossi’s organization is a big proponent of arts organizations teaming with congregations that have extra space, and it’s currently soliciting dance groups and houses of worship interested in connecting.

During the past year, she’s seen religious facilities utilized for food relief, vaccination hubs and virtual learning space for kids who don’t have internet access at home.

“It’s become even more clear, in this pandemic, how important that these buildings and the facilities can be to their communities,” she said.

THE CITY is an independent, nonprofit news outlet dedicated to hard-hitting reporting that serves the people of New York.