Chronic absenteeism. Suspensions. Dropouts.

That is the current performance of students who are in foster care in New York City, according to one children’s advocacy group that recently reviewed public records from the NYC Dept. of Education.

The group, Advocates for Children of New York (AFC), which released a report last week evaluating the performance of students in foster care, says steps are needed to improve the education of these children and highlights glaring issues like chronic absenteeism, high dropout rates as well as low performance levels. However, the organization presents improvements that could be made to the system if the DOE takes on their proposed solutions to support the city’s roughly 7,500 foster care students.

“Although these students are in the care and custody of the city, they have some of the bleakest academic outcomes of any student group, and rarely get any attention,” said Randi Levine, policy director at AFC.

“Students in the foster system are disproportionately suspended from school, placed in special education schools, and chronically absent and have appallingly low reading proficiency and graduation rates. For students who have to transfer schools, the outcomes are even worse.”

The report revealed that there are huge learning disparities between students who are in foster care and students who are not. It pointed to higher rates of chronic absenteeism, a greater number of suspensions and dropouts, lower math and reading levels, and lower graduation rates.

“I think there’s a number of really concerning statistics,” said Erika Palmer, an attorney at AFC. “The chronic absenteeism numbers are very concerning.”

Other data was equally concerning, according to the report.

Nearly 85% of students in foster care are not proficient in math, and four out of five are not reading proficiently, according to New York State tests for third through eighth grades.

Foster care students who attended school were also issued suspensions by the DOE at nearly four times the rate of non-foster care students.

The DOE issued 133 suspensions for every 1,000 students in foster care between 2016–17 and 2018–19, according to the report. The high suspension rate has led to a greater number of students dropping out and lower graduation rates compared to non-foster students.

The reasons leading to suspensions and trouble in school are multi-pronged and can oftentimes be tied back to issues at home or deteriorating mental health. For foster care students, these issues may be exacerbated.

“Students might act out or become aggressive because they’ve experienced bullying or they have fear that they’re going to be hurt,” Palmer said. “Whether that’s experiencing abuse or neglect or their parents struggling with mental health, substance abuse issues or their parents passing away or becoming incarcerated, that is a trauma for that young person. If they continue to move homes or continue to have more losses that just compounds it.”

Only 40.2% of foster care students who entered ninth grade in 2017 graduated in four years. Though these numbers have slightly improved from data in 2016, that’s compared to 81% graduation rate for non-foster students.

The problem is worse for foster care students who transfer schools, which is common.

For those foster students who started 9th grade in 2017 but transferred schools two or more times, only 18.2% earned a high school diploma in four years.

Palmer said she’s worked with foster youth who have been in 10 to 15 different households.

“Students in foster care continue to have graduation rates significantly below other students,” Palmer said. “If you’ve changed schools twice in high school and you are in foster care, you are more likely significantly more likely to drop out than you are to actually graduate.”

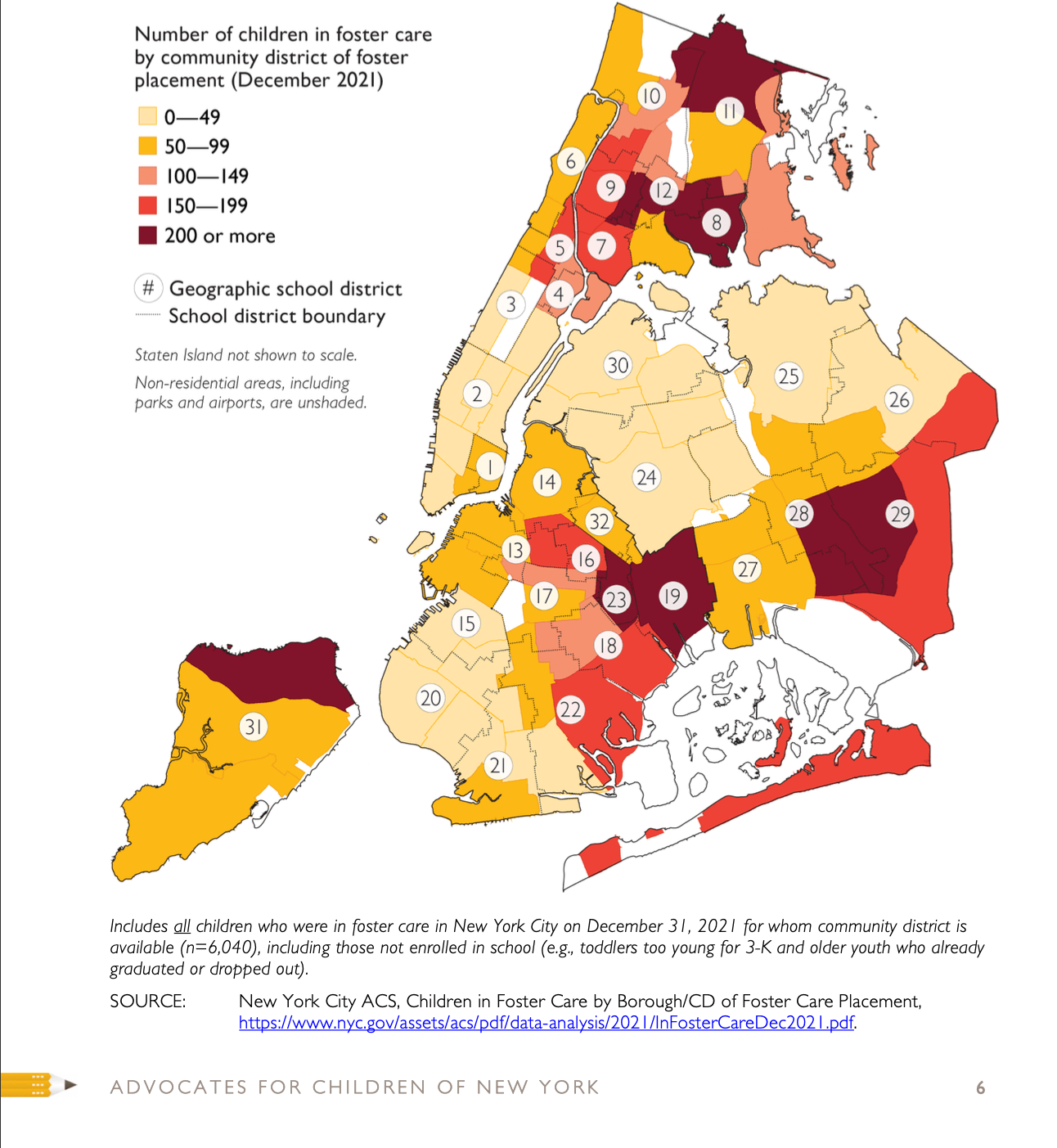

The report showed areas in New York City where there are large numbers of children placed in foster care: Jamaica and Hollis in Queens (parts of school districts 27, 28, and 29), East New York and Brownsville in Brooklyn (school districts 19 and 23), Williamsbridge, Parkchester, and Morrisania in the Bronx (parts of districts 8, 9, 11, and 12) and St. George and Stapleton on Staten Island (part of district 31).

Students in foster care have other challenges, including with transportation.

While school transportation is an area that Palmer said the DOE has improved over recent years, she said there are still glaring issues.

“It can take a very long time for that busing to be set up,” Palmer said. “In the meantime, we need interim transportation options.”

Palmer said that the education department also doesn’t provide busing outside of school hours, which prevents many students in foster care from participating in after school programs.

Many of these students rely on school buses to get to and from school, since they often attend schools in a different borough, Palmer explained.

The AFC, based on their findings, have several recommendations for the DOE.

These include: training school staff on the needs and legal rights of foster care students and their families; ensuring foster care students have access to comprehensive mental health services; improving communication between schools, families, and foster care agencies; and guaranteeing door-to-door transportation for foster students.

The DOE says that it is taking steps to improve the educational outcomes of these students and is building a foster care team.

“The foster care team is working collaboratively with school administrators, social workers and counselors to increase communication with both foster parents and biological parents,” said Jenna Lyle, DOE spokesperson. “The team is also engaging parent coordinators and school and district leadership in a dedicated professional learning series on the educational rights of foster parents and biological parents.”

The DOE has hired eight out of the nine foster care team members as of last November, Lyle said. The hiring process for the ninth team member begins in February.

“The issues and findings cited in this report comprise our motivation for the creation of a team wholly devoted to serving our students in foster care,” Lyle said.

The DOE has much to do, based on the report’s findings.

Over a period of five-year period, from the 2016-17 school year to the 2020-21 school year, DOE data showed that half of all students in foster care were chronically absent.

The report, however, cited several examples where the city appears to be addressing the needs of foster care students—including the DOE’s new foster care team flagging troubling attendance data for a foster care agency.

Palmer said that there is a renewed sense of hope that the new DOE team could identify and tackle systemic barriers preventing foster students from finishing their education successfully. Nevertheless, she said, improvements are needed.

“This is a population of students that really needs these extra supports,” Palmer said. “Now we see it in black and white, and the numbers are pretty startling. It shows there’s so much work to be done, and hopefully it can create a sense of urgency.”