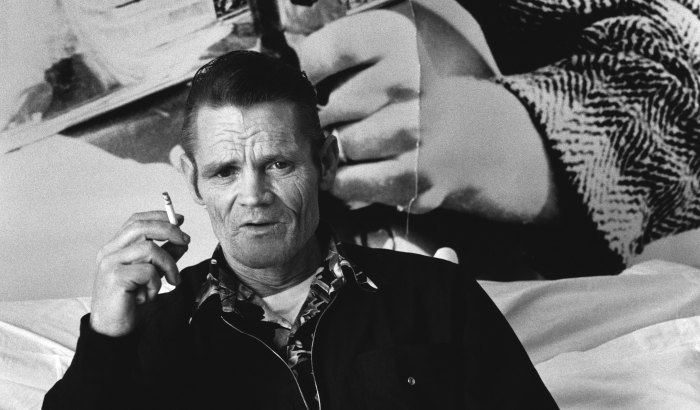

Brooklyn’s Syed Bukhari drove a black car limo, but then COVID-19 hit and that all changed. He gave up his $450 a week car because there was no business, but opportunity was knocking when he was asked to deliver food full-time to the home-bound, he jumped at the chance to help people.

It was not without risk – COVID-19 was killing and making thousands sick in New York City.

But Bukhari became one of the many livery drivers who risked their health to deliver food in the Taxi and Limousine Commission’s Emergency Food Delivery initiative, which is part of the “Get Food NYC Program,” responsible for delivering nearly 65 million meals to the home-bound and elderly since the spring.

The TLC held their seventh annual Honor Roll to honor drivers who have done extraordinary things for city residents. The agency held a virtual ceremony Tuesday, during which Bukhari was honored for his steadfast efforts to help the home-bound.

The 37-year-old Pakistani immigrant and resident of Midwood had already been doing that as a TLC driver for more than 15 years. In that span, he did more than 780 routes, which is about 40,000 meals to the home-bound. But this time it was different and had serious risks to him and his family. But he was ready to step up.

“I was a bit scared and so when the pandemic started, there was no work, so I was worried what to do,” Bukhari said, standing at his white Nissan NV 200 mini van that he now uses – plenty of space for food deliveries. “The fear was a real thing and I didn’t know what I was going to do.”

He decided to step up despite the COVID-19 danger and help those who couldn’t help themselves.

“Someone needed to help them to get food,” Bukhari said. “All my friends were mostly in same field, and they received the email with the offer, but they were saying it was too risky. They said safety comes first and there were chances of getting sick, getting the virus and bringing it home. But so many people were in quarantine and they were depending on the city so if nobody brought food, what will happen to those people? So I was there the first day and the last working with them.”

Bukhari came to the U.S. from war-torn Pakistan with his parents 22 years ago, and has since married and has four children – three boys, ages 4, 16, and 18 and a daughter, 13. His parents sought a better life, improved education opportunities and mostly “work.”

He said his daughter and oldest son expressed great concern for their father: “Everybody was scared.”

“When the pandemic started, we opened the TV and there as so much negative on each channel talking about how many people died,” he said. “They were talking about people dying, but not talking about recovering or what doing to recover, what people were doing in quarantine, medicine, most of the people drinking tea with lemon, that helps, nobody was saying anything about that. But people needed help so I wanted to help.”

The work wasn’t easy for Bukhari.

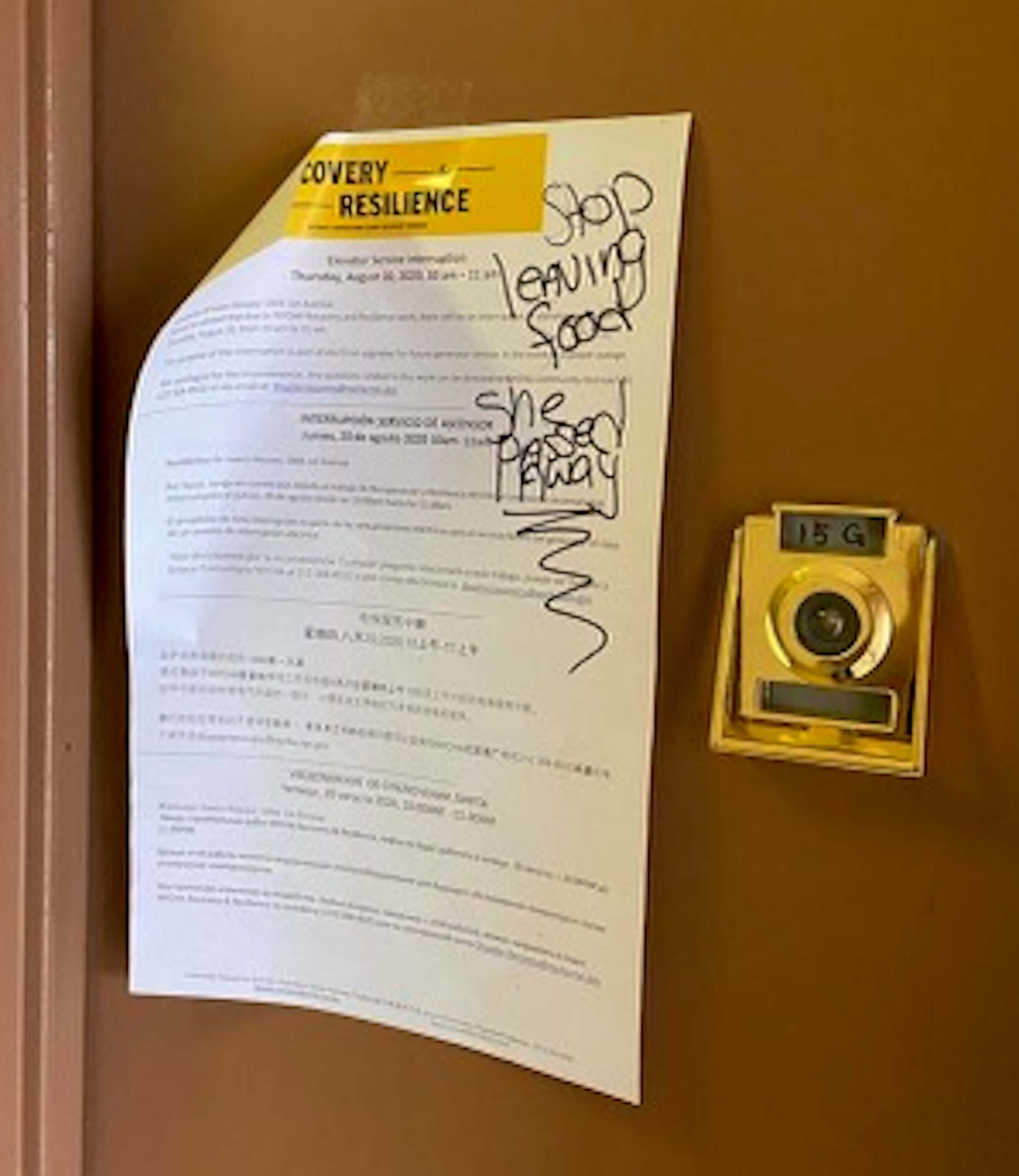

He would show up to buildings and there would be signs warning that residents were infected with the virus. Some people didn’t even open their doors for the free food and would ask him to just leave it at the door. They were poor, elderly, disabled, a few were blind. But mostly, they were the city’s most vulnerable to COVID-19 that claimed the lives of nearly 20,000 New Yorkers.

In one case, a sign was hung on the door turning away the food – the senior had died.

“I began doing this because it made my heart happy,” Bukhari said. “I felt it was my duty – our neighbors needed these meals. What if doctors and nurses didn’t want to go to the hospital because of COVID-19? Somebody needs to step up and serve our community. Why not me? I said to my friends, listen, everything is risky – you can get into accident and die. If I catch the virus, I will have gotten it catch regardless because people who didn’t work they caught it.”

While Bukhari is not a religious man, he has faith that doing good for people is “good karma” and “when you do good for people, good will come back to you.”

“The people I delivered meals to may never have thought about taxi drivers before, but everyone I delivered to blessed me and I believe God was watching over me while I served the community,” Bukhari said. “Some of the best moments delivering emergency meals included helping people with disabilities and the elderly. Some of the people I brought meals to were not even able to leave their beds, and I’m glad that I was able to support them in their hour of need.”

He said many of his friends choose to collect unemployment, but “I choose choice number two and it was worth it.”

“I would go to housing and sometimes the door bell didn’t work and people would have to run downstairs to get their meals – they would come and say ‘I love you so much, God bless you.’ Every day I’d hear that and that was the greatest tip I could receive.”

Bukhari said he is now awaiting word from the MTA, where he has been on a three-year waiting list for a job. He was getting ready to take a drug test moving forward.

Looking back, Bukhari hailed the work of first responder’s and front-line workers in hospitals for helping during the worst of the pandemic and their continuing efforts. He asked others what they did during the crisis.