In a city filled with overflowing garbage cans, teeming construction dumpsters and countless used coffee cups, saving the planet can seem like a futile proposition. Throw in climate change, and all those food scrap bins almost seem like a drop in the recycling bucket.

One group taking a broad approach toward preserving and protecting our planet is the East Village-based Green Map System, a global network of people creating graphic projections intended to integrate nature, culture and sustainable living.

“We’ve been listening, watching and creating examples that help people find their own pathway through the process of making a map,” said Green Map founder Wendy Brawer.

Brawer and her mapmakers catalog green sites, trying to figure out how to live in a more sustainable way. Green Map has worked with city agencies, universities, nonprofits, corporations and even children.

“Green Map is a locally led, globally linked movement mapping local nature, culture and green living places in communities around the world,” Brawer explained.

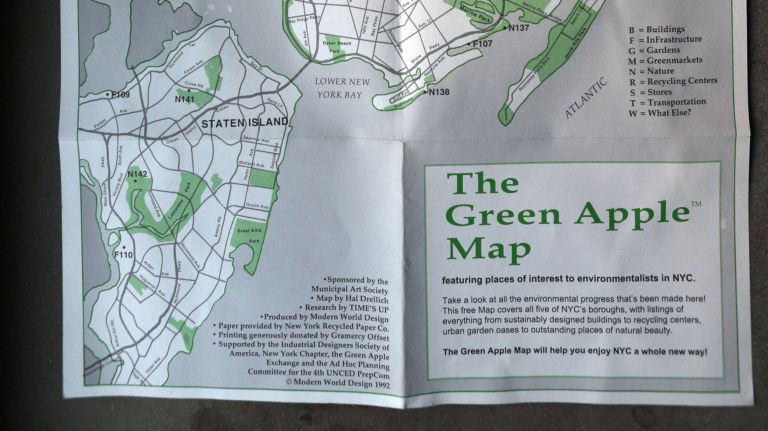

There are now about 600 locally published Green Map print maps, as well as 600 online interactive maps in dozens of countries as far away as Australia, China, South Africa and Israel. The Public Library has hundreds more maps, as well as outreach and educational materials.

Brawer, a 2017 TED resident, says every neighborhood, from Gravesend to the Upper East Side to Woodlawn, offers something of ecological or cultural value.

“Maybe it’s a historical building, maybe it’s a tree you loved as a child, maybe it’s a library; all of these things are on the Green Map,” she explained.

On the first day of spring, Brawer sat in her office near filing cabinets filled with some of the hundreds of green blueprints from around the world. Gazing out the window at a community garden across the street, Brawer sounded like a cross between a socially conscious lobbyist and a pragmatic optimist.

“The trees, the community gardens and parks make us happy and healthier. They reduce stormwater on rainy days and increase our comfort and sense of well-being on hot days,” Brawer said.

Recent reports detail how many bees are dying, how the icepacks at the poles are melting, and, in recent weeks, how Midwest states have been inundated with flooding — yet climate change deniers abound. What’s a tree hugger to do?

Brawer cites one example of proverbial mountain-moving: Her “Are We Trashing the Apple?” map from 2000 revealed 48 acres of waterfront that would have been converted to waste transfer stations.

“In 1999 people learned about a plan to site garbage transfer facilities in Red Hook, Williamsburg and the South Bronx, which would have meant countless trips a day of garbage trucks into low-income communities of color on the waterfront. Mapping and community outrage stopped the plan and saved air quality in those neighborhoods,” she said.

Brawer started out as a designer and a mixed-media sculptor in Seattle, but slowly shifted to become an eco-designer.

“I was leaving my art career behind,” she recalled. “I wanted a bigger voice than I knew art would give me.”

In 1988 she took a night school class in industrial design at Cooper Union, and by 1991 she was at the United Nations as an NGO, sitting in a room full of New York-based nonprofits.

“We were preparing for five weeks of out-of-town sustainability experts who came to negotiate what became Agenda 21 for the Earth Summit in Rio 1992, the UN Conference on sustainable development.

“I started thinking about the individual’s experience. Would they notice the signs of progress toward sustainability?,” she said.

Her design background kicked in, and the first map design in 1992 listed 143 sites, including greenmarkets, community gardens and bike groups. Brawer called it the Green Apple Map. She met with a dozen friends to brainstorm and, six weeks later, 10,000 copies were printed.

“By making these maps you could bring people together, to share knowledge and network and to build capacity. It makes you more appreciative of assets you have and more aware of conditions you need to address,” she said.

But what does Green Map mean to the retiree sitting on a bar stool in Bay Ridge, or an Upper East Side hedge fund trader?

“People definitely perk up when they see a map of their neighborhood, mapping issues, dangers, and resources . . . where they actually live and spend their time,” said radio producer Aaron Reiss, who worked for Green Map for several years. Reiss said the maps can alert people to redevelopment or rezoning in their neighborhood.

“After Sandy, Green Map created three maps; in English, Spanish and Mandarin, showing different resources for disaster preparedness and environmental resiliency. Those were aimed to empower people and prepare them if a disaster ever happened again,” Reiss said.

Elissa Sampson created an interactive Garden Green Map of community gardens in 2009.

“When the gardens got attacked in the ‘90s because of gentrification and because of the value of the land they were on, people started defending the gardens because they understood the gardens saved the neighborhood,” Sampson, an urban geographer, explained. “They were cultural and green resources for urban dwellers. I wanted to be able to explain visually where these gardens were, and why they were important.”

The Green New Deal is another example of how Green Maps have helped lead people, as the mapping inspires innovation and investment in more green jobs and renewable energy. City officials also are coming around to Brawer’s point of view. Earlier in March, City Comptroller Scott Stringer tweeted, “Imagine if, instead of tearing down parks to build highways, we flipped the script and replaced highways with beautiful public parks? That’s what we are proposing to do with the BQE. Let’s get this done.”

Brawer remains tireless in her efforts to make every day Earth Day. She points to the 5,000 street trees in her downtown neighborhood that provide carbon dioxide reduction, stormwater capture and pollutants removal. She is also rallying against a plan to bury East River Park under 8 to 10 feet of soil, a drastic change from an original plan to save the park and adjoining neighborhoods from flooding.