Guy Woodard has always been meticulous about his work.

Whether he was focused on crafting an oil painting or forging a check, Woodard boasts a keen eye for detail.

“To me, that was art,” Woodard says of his past life as a forger and counterfeiter. “That’s the only art I could do that could pay the rent.”

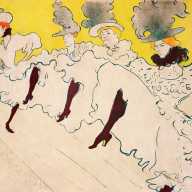

Now Woodard’s stunning drawings are getting accolades from the art world and being snapped up by celebrities. An exhibit of his work titled “We the People,” featured at the Howl! Happening gallery in the East Village, closes Sunday after a successful four-week stint.

Visitors linger over his intricate drawings, which range from the peaceful and pastoral trees in “Black Forest” to the nightmarish “Home Invasion” where a young boy sees his family restrained and held at gunpoint by law enforcement officers.

It’s almost impossible to comprehend that the tool Woodard uses to create these striking images is a simple ballpoint pen. Each takes months to complete and involves hours of painstaking work.

The decision to use pens came to Woodard during several stints in prison for forgery and counterfeiting schemes that involved bank checks, identification cards and government documents.

He was not allowed to use the oil paints he preferred.

“They had pastels and acrylic paint but I can’t paint with that,” said the 68-year-old Woodard. “So I taught myself to actually paint with a ballpoint pen.”

He got the idea after spotting a grainy gangster photo from the 1930s in a newspaper.

“I looked at it and it was all just dots and I thought I could do that.” he recalled.

Growing up in Harlem, Woodard amused himself by drawing and reading classics such as “Treasure Island.” A childhood illness kept him at home while his siblings played outside.

“I could draw before I could write, before I could read,” he said.

Turning it into a career was a mystery to him.

“Artists need a sponsor and I guess the feds were my sponsor,” he said dryly about being able to focus on art during the years he was incarcerated. “They fed me and paid the rent.”

After he was released in 2015 and living in a men’s shelter, Woodard sought out David Rothenberg, who founded the Fortune Society to help formerly incarcerated people get a fresh start. Woodard was a listener of Rothenberg’s radio show on WBAI.

“I looked at his portfolio and told him they were too good to be in a shelter,” said Rothenberg. “We gave him a place to store them and then a place to work. He was ready for a change.”

Woodard began teaching young people in the Fortune Society’s Alternative to Incarceration program. His eyes light up when he talks about how reluctant students grow confidence in the class.

“It’s not so much that I expect them to be artists,” he said. “But they will have done something they thought they couldn’t do. So the next time they think they can’t do something, they will try.”

Artist Norman Rockwell was an inspiration for many of Woodard’s early oil paintings. And, like Rockwell, he proudly refers to himself as an illustrator.

“If I’ve got to tell you what it is I didn’t do it,” said Woodard of his artwork. “There’s a message here. This isn’t abstract.”

One piece titled “Chicago” shows a young boy walking, wearing a plastic shopping bag as a backpack. In “Sao Paulo,” two boys, shirtless, barefoot and clutching a soccer ball, sit on steps.

“Poor kids playing don’t know they are poor,” he said.

Many of his pieces selected for the exhibit have strong social justice themes, especially “Take A Knee” which shows the faces of Aiyana Jones, Andy Lopez, Tamir Rice and Trayvon Martin in front of targets. All four young people were unarmed when they were shot and killed by police officers, except for Martin who was shot by a civilian.

Other artwork surrounding those pieces are created to look like their diplomas and other awards.

“It’s imagining the heights they might have gone," Woodard said.

Gallery director Ted Riederer said reaction to the exhibit has been overwhelmingly positive from a diverse array of visitors.

“There are the artists who appreciate the virtuosity of his techniques and then more conceptual fans who love the ideas of his background and how it influences his work,” Riederer said.

Woodard said he doesn’t want his life story to be an example for others, but he also isn’t ashamed of it.

‘I wouldn’t change my path because I wouldn’t be here,” he said, standing in the gallery. “I’d be somewhere else.”