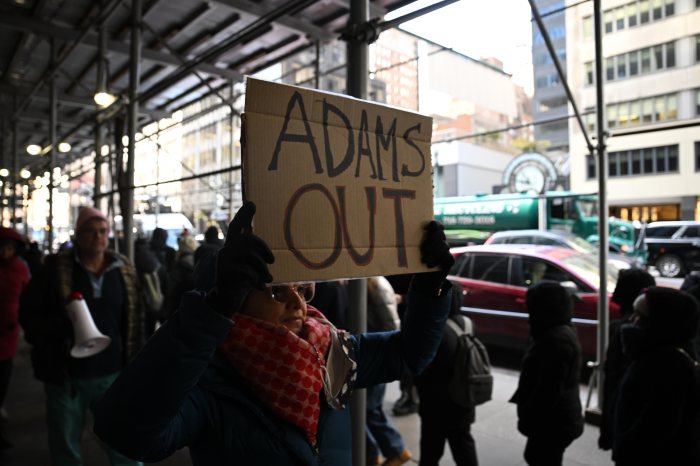

BY DENNIS LYNCH | Hate crimes have surged in New York City during this divisive election year — and show no signs of letting up — but authorities at the state and local levels are mobilizing to address the problem.

The NYPD has logged 35 percent more bias crimes so far this year over the same period last year — rising from 260 to 350 — a rate on pace to make 2016 the worst year for hate crimes in the city in at least eight years, according to the available police figures.

Last week the NYPD reported that there have been at least 43 bias attacks since Election Day, more than double the number for the comparable period in 2015.

“The trends are a bit disturbing,” said Police Commissioner James O’Neill during a radio appearance on November 20. “More than an uptick.”

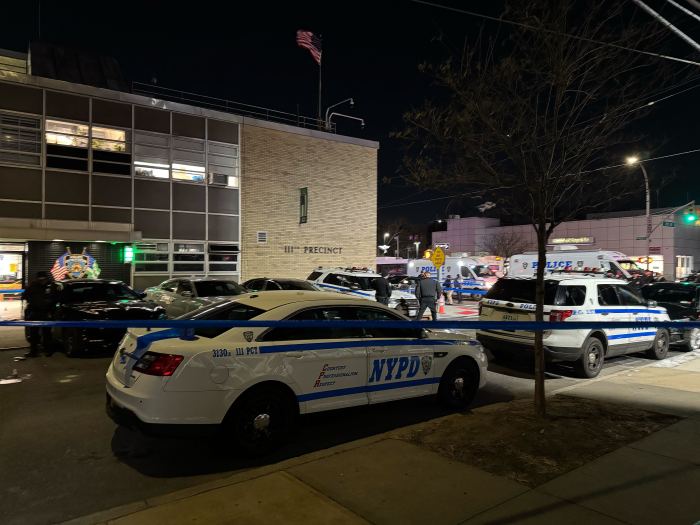

This past weekend, a Brooklyn man threatened Aml Elsokary, an off-duty Muslim police officer, with his pit bull when he came upon her, wearing a hijab as she walked with her son. In 2014, Elsokary was awarded for bravery for running into a burning building to save a small child and a grandmother. Another Muslim woman wearing a hijab, a transit worker, was shoved down a staircase at Grand Central Terminal.

Hate crimes against Muslims more than doubled from last year and anti-Semitic crimes rose nine percent, O’Neill said, attributing the increase partly to the heated rhetoric from the campaign of President-elect Donald Trump.

The spike in hate crimes around the state prompted Governor Andrew Cuomo to create a State Police Hate Crime Unit comprised of investigators trained as “bias crime specialists” who will assist local district attorneys to prosecute hate crimes.

Nationwide, the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC) has collected reports of more than 900 incidents of “hateful harassment” perpetrated around the country since Donald Trump defeated Hillary Clinton on November 8. The organization compiled the list from news articles and social media, but also directly collected information on its own. “Anti-immigrant” incidents were the most prevalent, and more than a third of those alleged incidents occurred in the first three days following Trump’s victory.

But are there really more hate crimes being committed this year, or are we only seeing more because the media is covering them? Looking at the numbers, John Jay College of Criminal Justice professor Frank Pezzella said that, unfortunately, it’s likely to be the former.

“I think the election illuminated how divisive things really are, and hate crimes spike during times of economic upheaval, strife, and the emergence of identity groups — every group wants to be identified and taken care of because of the problems that relate to them,” Pezzella said, referring to a troubling normalization of formerly fringe ideologies, such as the “alt-right” white-nationalist movement with its “unabashed advocacy to return back to the things that used to be.”

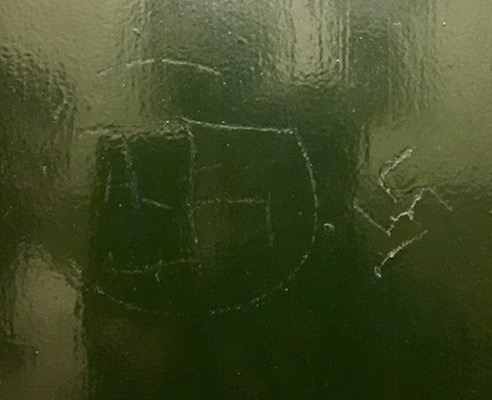

The connection to the presidential election is clear in some cases here in New York. The NYPD is investigating the swastikas and “Go Trump” messages crudely spray-painted at Adam Yauch Park in Brooklyn Heights on November 18 as a hate crime.

West Side State Senator Brad Hoylman, an out gay man who belongs to Congregation Beit Simchat Torah, a Manhattan LGBTQ synagogue, was in the news twice in the last several weeks for encountering anti-Semitic messages. First, a woman found a swastika carved into a door in his apartment building, which made national news. Then a few days later, the senator opened an envelope in his mail to find an anti-Semitic, anti-Israel pamphlet with pictures of flames, human sacrifices, and Bible quotes.

The return address led to a known far-right extremist living in Arizona. Hoylman said he believes the acts were directly related to Trump’s election and the president-elect’s choice of Steve Bannon — whom he termed a “white nationalist” — for a top advisory post.

“I’m very concerned about [the trend of hate crimes] especially since Steve Bannon has been put in a top White House post,” he said. “I strongly believe Trump should rescind his appointment. All of us should be concerned about that.”

The SPLC has not verified every incident it has recorded, and there won’t be an “official” number for this year’s bias crimes nationwide until 2017 when the Federal Bureau of Investigation releases its hate crime report for 2016 as part of its Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR) program. The UCR is the most comprehensive report on hate crimes in the country. But watchdogs warn that the UCR is flawed, and even if it were perfect, it wouldn’t really paint the whole picture.

The UCR is entirely voluntary and at least 4,000 law enforcement agencies nationwide do not participate in its hate crime reporting. Around 1,750 departments out of the 15,000 departments that do participate have reported hate crime incidents.

Even New York State under-reported its bias crimes in past years due to inconsistencies between the city and state hate crime reporting that were discovered after Hoylman successfully petitioned the state comptroller to audit the two systems in 2013.

The comptroller found that between 2010 and 2012, there were errors in reporting when the NYPD communicated its statistics to the state, meaning the state counted fewer hate crimes in the city than the NYPD had, and subsequently reported fewer numbers to the federal government.

For example, the audit found that the state reporting system only allowed a single bias per incident filed, even if there were multiple at play. The comptroller pointed out in one case “an agency reported multiple biases on its hate crime incident report: both anti-male homosexual and anti-Arab. Because its system allows staff to only record one bias per incident, the division reported the case only as an anti-male homosexual incident.”

But even with full reporting, Pezzella said that the national figure would likely still be lower than the actual number of bias incidents that happen nationwide. For one, small departments across the country might not have the resources to properly train their officers to identify a hate crime, which isn’t as easy as it sounds.

An officer responding to a call typically has only a few minutes to assess if bias played a role in an incident, Pezzella said. Offenders, knowing that a hate crime is more seriously punished, often try to hide their bias, and the vast majority of incidents are not as cut and dry as an offender admitting to a deep-seated hatred of gays, Jews, or black people, for example, Pezzella said.

“Just calling someone a name is not enough to do it, and often what happens is officers think, ‘Why take the chance to arrest for a hate crime when you can just arrest for an ordinary crime?’ There’s possibly a better chance of sticking, of getting a conviction,” Pezzella said. “You also have to prove motivation.”

The officer has to identify that a perpetrator had a “bias motivation” during the act of a crime such as a robbery, harassment, or assault to arrest a person for perpetrating a hate crime.

Political affiliation is not grounds for a hate crime charge at the federal level or by New York state law, so many politically motivated assaults in the news recently won’t pass muster.

For example, the NYPD is not investigating as a hate crime the case at a Boerum Hill diner when a man punched a woman in the face after an argument about Trump’s election.

Similarly, anti-immigrant comments recently made by visitors to the Tenement Museum on the Lower East Side aren’t serious enough in the eyes of the law to warrant hate crime status either.

That type of incident is typical of what many have encountered this year, according to Shelby Chestnut of the New York City Anti-Violence Project, which serves the LGBTQ community.

“So much of what people are experiencing doesn’t necessarily fit into the framework of a bias incident that police deem to investigate,” she said. “There’s more of a general feeling of being unsafe in our communities. There’s a sentiment that it’s suddenly okay to be anti-LGBT, anti-immigrant, anti-Muslim following this election.”

Pointing out that victims of hate crimes are not always willing to report incidents to police in the first place, Pezzella’s John Jay colleague Eric Piza noted that the federal Crime Victimization Survey last year found that 47 percent of victims of all types of crimes do not report them to police.

“There’s a whole host of reasons why people might not report a hate crime,” said Piza, an assistant professor at John Jay and former Newark Police Department crime analyst. “One is that for the victim, it’s a traumatic experience and people want that to be over as soon as possible. In a lot of cases, you have to wait for police, make a statement, and, especially if there’s a low likelihood of the person being caught, there’s a low chance they want to do that. And the other side of it is that some people think the police won’t take their side of the story.”

Pezzella added that the NYPD has a “built-in problem” because many groups protected by hate crime statutes often have, or historically had, a strained relationship with the police — including LGBTQ individuals, Muslims, and people of color. The fear of or animosity toward police can discourage victims from dialing 911.

Chestnut said that fear of deportation or legal trouble is particularly palpable in the immigrant LGBTQ community, even in so-called “sanctuary cities” such as New York, where the police department doesn’t work directly with federal immigration enforcement agencies.

“It is ultimately dangerous to report an incident of violence to police where you could be targeted for your immigration status, [and] if you’re an LGBTQ immigrant you are at a much greater risk — the fear for reporting is very real,” she said.

Many LGBTQ immigrants who are deported face risk of further victimization in their home countries if their status becomes part of their official record.

Pezzella suggested that the NYPD reach out and let people know they want to hear their stories, and said that assigning out LGBTQ or foreign-born officers to neighborhoods where those communities are experiencing harassment could encourage people to report crimes. The UK did that with LGBTQ officers and had success, he said.

Chestnut noted that witnesses to hate crimes can help by refusing to remain silent and asked people to sign AVP’s “bystander pledge” to act if they witness hate-motivated violence. The pledge, promoted with the hashtag #IWILLNOTSTANDBY, includes advice on safely intervening to halt a bias attack.

The man who targeted Hoylman may have been 3,000 miles away, but the state senator believes that people who want to change the nation’s toxic political climate for the better should start in their neighborhoods.

“As New Yorkers are frustrated by the national political climate, they should get involved — join the community board, go to precinct community [council] meetings, get involved with your block association, contribute money to your favorite advocacy group,” he said. “There’s the saying, ‘A crisis is a terrible thing to waste,’ and I think there’s a lot of work to be done to restore the feeling of safety and respect in our national political dialogue, and I think starting locally is a good option.”

Chestnut agreed with Holyman’s advice to think nationally and act locally, saying that New York should be an example for the rest of the country. “In New York City, we’re fortunate that there’s an organization for every reality that someone is facing,” she said. “We should ensure that resources and support go to regions of the country that don’t have as much wealth as we do — and think of how New York City can lead that.”