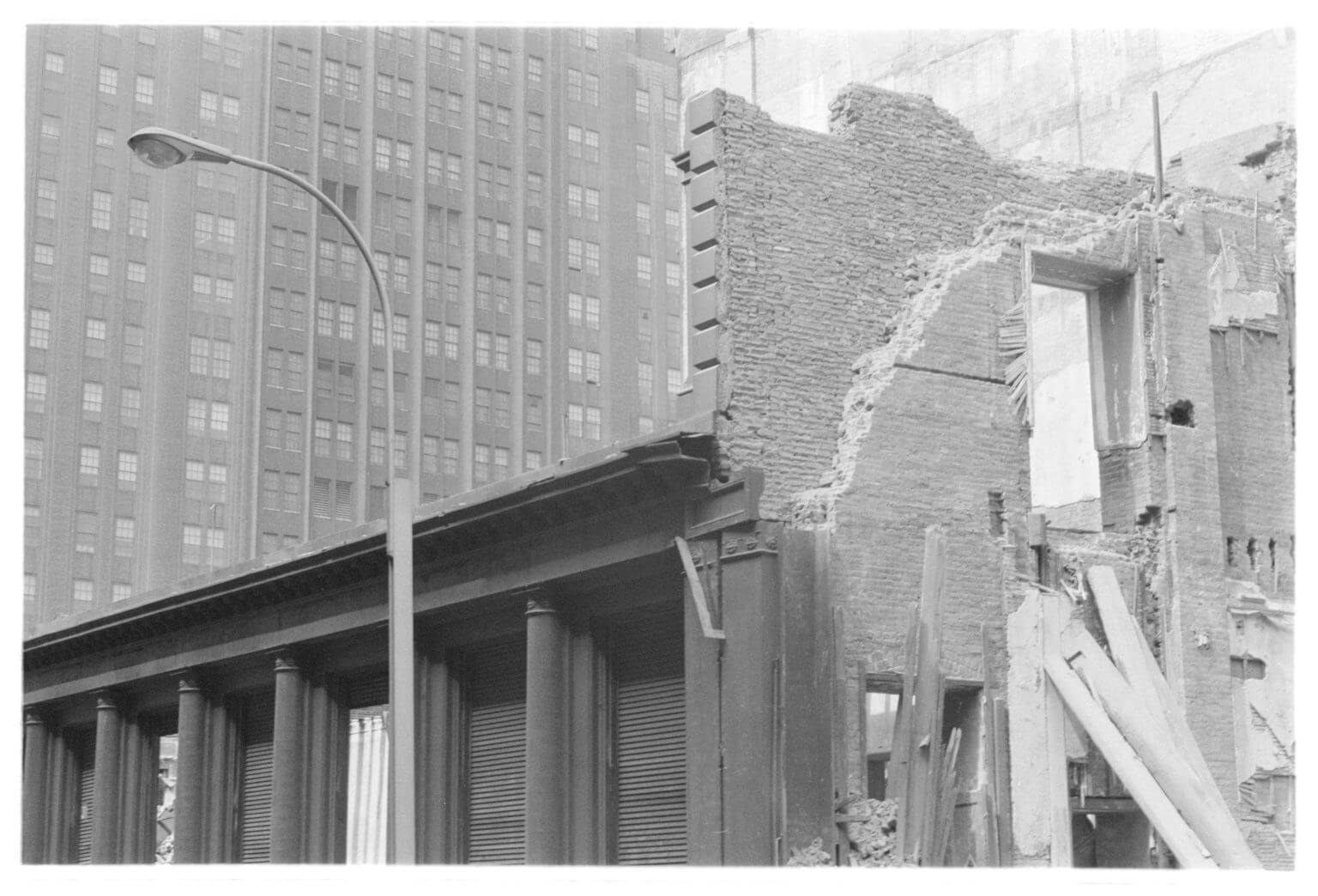

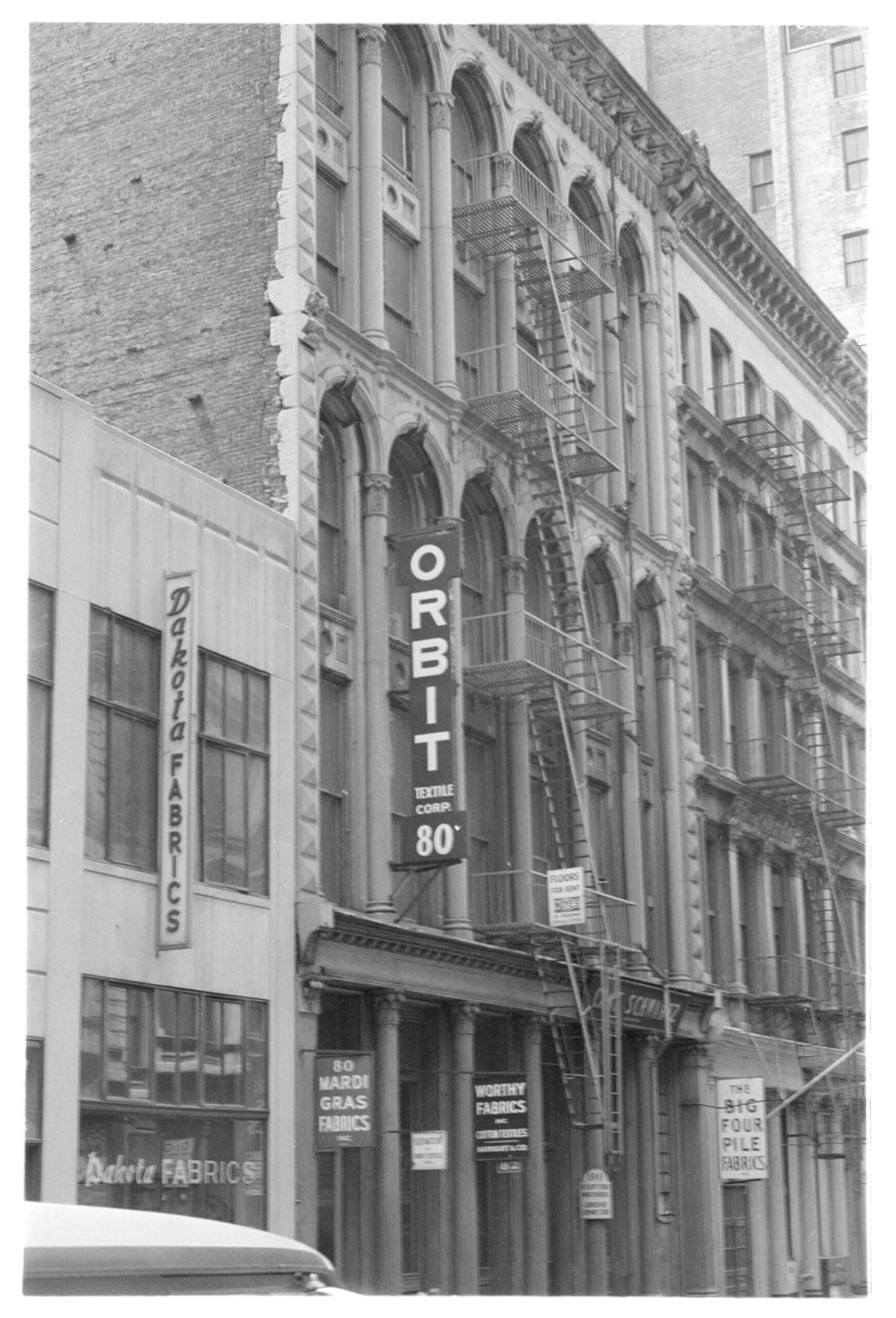

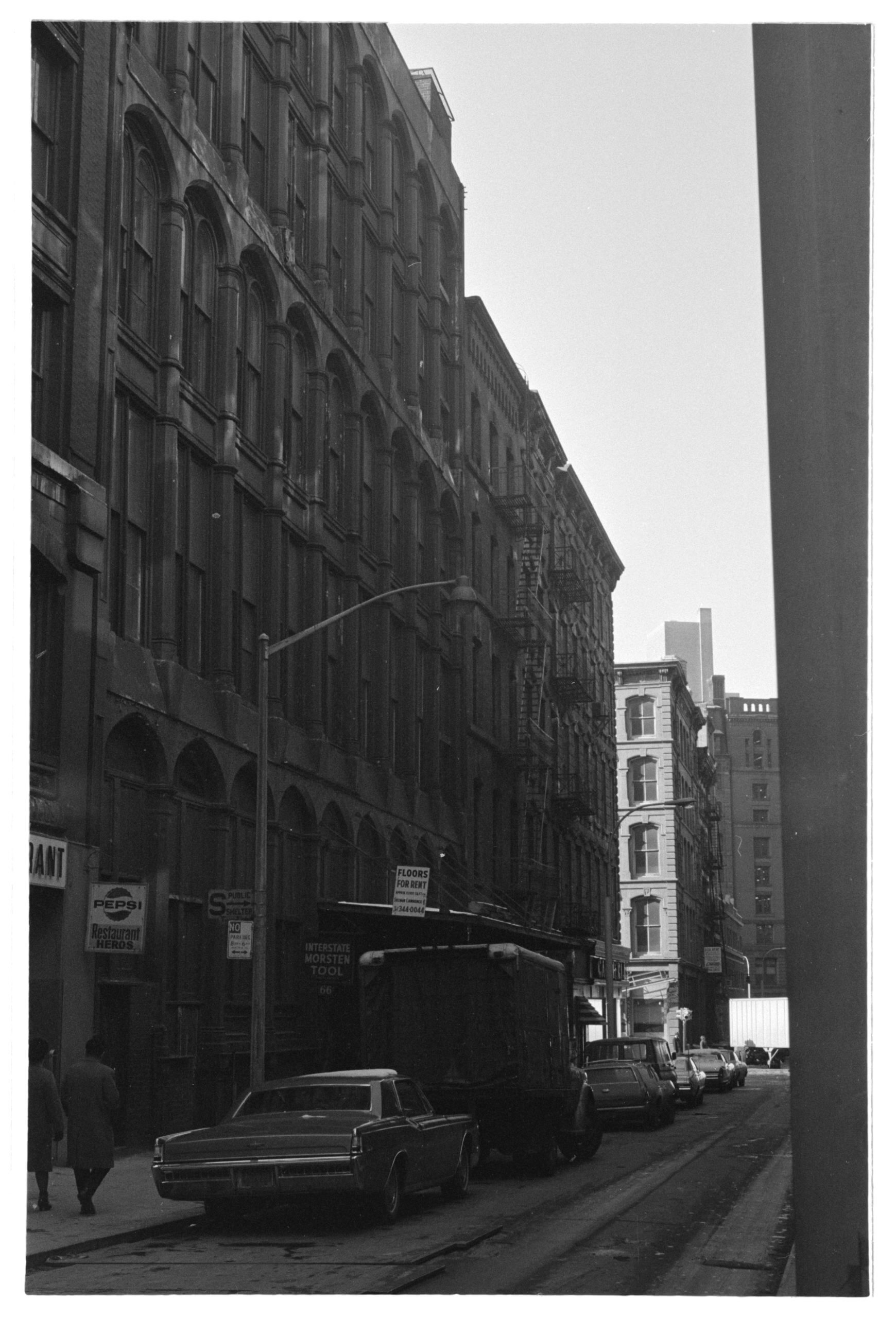

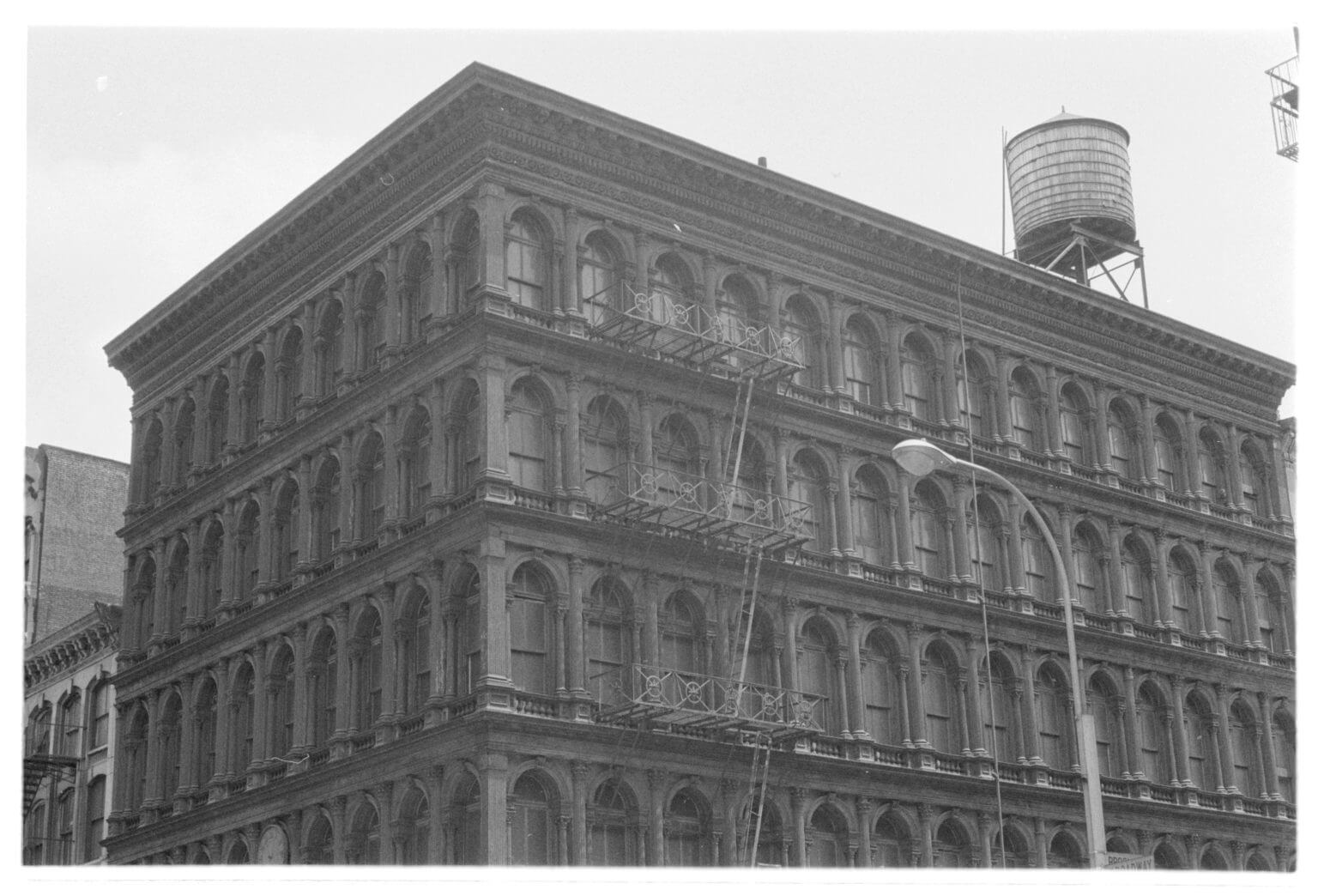

SoHo and Tribeca faced an uncertain future more than 50 years ago when a young architecture student named Edward LaGrassa took out his camera and walked around the communities, snapping pictures of buildings that seemed destined to meet the wrecking ball.

LaGrassa photographed scores of historic cast iron industrial buildings, many of which sat vacant or underutilized amid the era of urban renewal. Few believed they would last the next decade; a large section of Lower Manhattan had been torn down as part of the Washington Street Renewal Project, and much of SoHo was in the path of the Lower Manhattan Expressway — one of master builder Robert Moses’ dream highways that many others saw as a destructive nightmare.

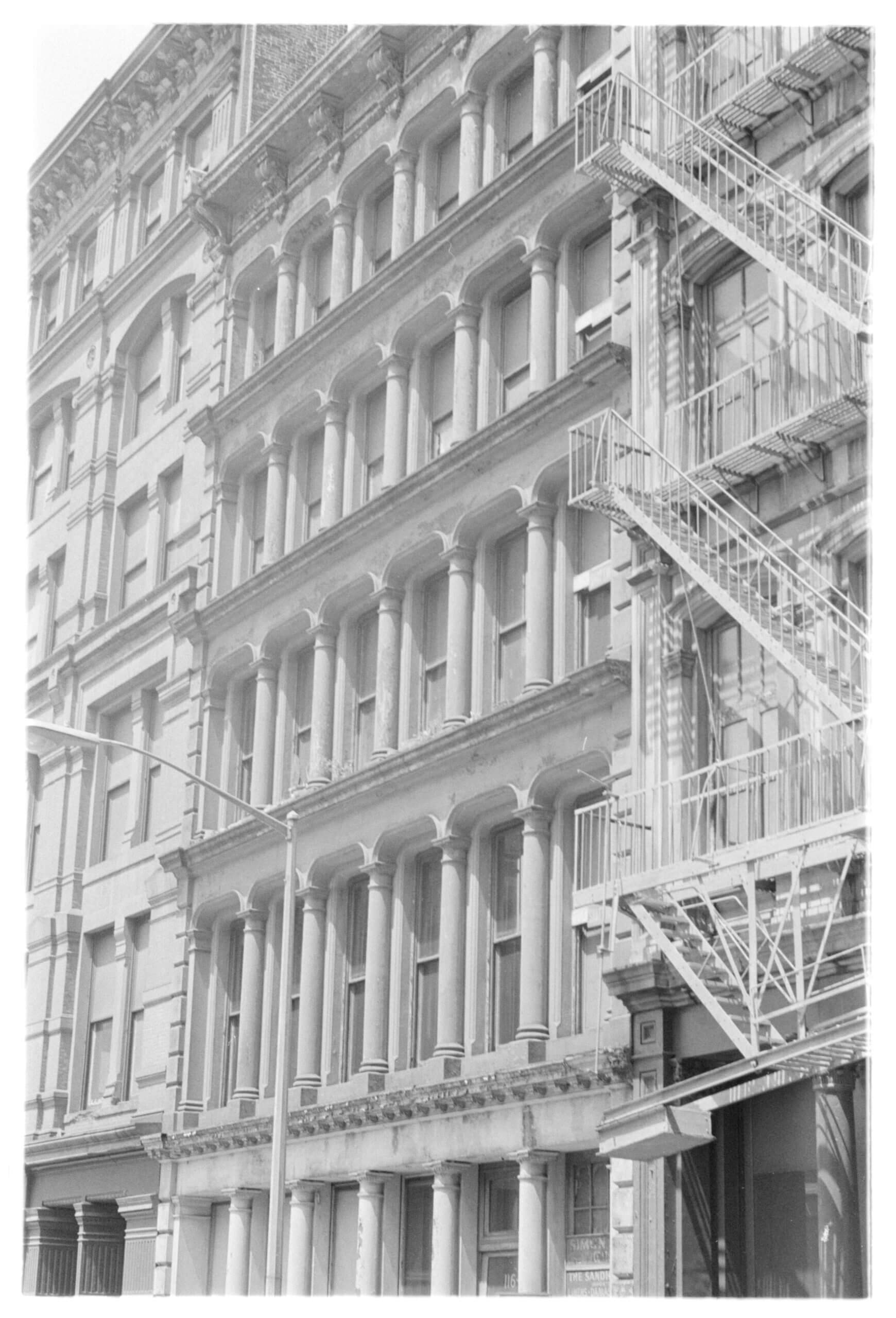

But the expressway was never built, and while some of the historic buildings wound up being demolished, the majority of them remained — and found new life as artist’s lofts over the five decades that followed. The area evolved into one of the most posh neighborhoods in all of New York, and now its future is up for debate again with the city setting its sites on changing the community’s zoning laws to foster in a new era of economic development.

That’s where LaGrassa’s photos come into the picture.

Recently, LaGrassa donated his collection of SoHo and Tribeca images snapped around 1969 to Village Preservation, the nonprofit group which advocates for the historical preservation of buildings in SoHo and NoHo, Greenwich Village and the East Village. It is also among the most vocal opponents to the proposed SoHo-NoHo rezoning, and has pitched an alternative plan that, its executive director Andrew Berman says, provides more affordable housing and economic benefits than the city’s proposal.

Berman told amNewYork Metro that LaGrassa recently reached out to Village Preservation and donated the photographs he took more than a half-century ago to its archives. The black-and-white images provide the viewers with a glimpse of how SoHo and surrounding areas appeared at one of the most crucial points in its history — when its future was very much in doubt.

Prince Street looking west-southwest from Greene StreetVillage Preservation/Edward LaGrassa Collection

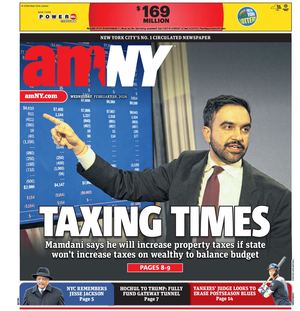

The SoHo-NoHo rezoning doesn’t resemble the Lower Manhattan Expressway plan — which would have rammed an interstate highway through the neighborhood, connecting the Manhattan and Williamsburg Bridges with the Holland Tunnel. But Berman suggests the rezoning would alter the community for the worse.

The city’s plan calls for the M1-5B zoning in the area, which has permitted the propagation of artists’ lofts for the past 50 years, to be changed in order to permit the creation of 3,200 new apartments — up to 494 of which would be designated as affordable housing units. The rezoning area would primarily impact manufacturing and loft spaces in the area bounded by Canal Street to the south, Houston Street and Astor Place to the north, Lafayette Street and the Bowery to the east, and Sixth Avenue and West Broadway to the west.

But that plan, according to Berman, would permit the alteration, and even destruction of some of the historic buildings which weathered the turbulent 1960s and saw new life as artists lofts. The alternate plan that Village Preservation pitched would seek new buildings only on open lots, garages and utilitarian structures in the community that would be in character with the area’s current building stock — and “ideally 100% affordable housing.”

“The beautiful architecture would remain and the new buildings would not only remain in scale, but also be much more dedicated to affordable housing for a much broader range of people in need than the city’s proposal,” Berman said.

Community activism, led by journalist and advocate Jane Jacobs, derailed Moses’ vision for the Lower Manhattan Expressway and gave SoHo a second chance. In many respects, Berman sees the photos LaGrassa provided to Village Preservation as a new way to help win over public opinion in the debate over the SoHo-NoHo rezoning.

“I think it’s important for people to see the beauty of these buildings and to recognize that 50 or so years ago, this battle was previously waged, and we almost made the wrong decision then,” Berman told amNewYork Metro in a phone interview on April 16. “Instead, [we can go] a more thoughtful route of preserving what’s there and building in character of the neighborhood. That’s something we should be considering.”

To view more of the LaGrassa archives, visit villagepreservation.org.