In her first State of the State address after being elected to a full four-year term last November, Governor Kathy Hochul on Tuesday laid out ambitious plans for tackling some of the state’s most pressing issues including an affordable housing shortage, high crime, a sprawling mental health crisis and workers’ pay not keeping pace with the cost of living.

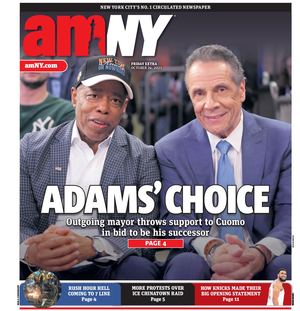

Hochul delivered her address in the Assembly chamber of the New York State Capitol, in front of lawmakers from both chambers of the State Legislature, judges on the New York State Court of Appeals and mayors from the state’s biggest cities — including New York City Mayor Eric Adams and Buffalo Mayor Byron Brown.

Despite the devastation wrought by the coronavirus pandemic over nearly three years, Hochul said, the state of the Empire State “is strong.”

“My fellow New Yorkers, after three very very painful, tragic years, I’m proud to strand here and say that the state of our state is strong,” Hochul said. “But we have work to do. Last year in the face of immense hardship and uncertainty, we endured. We proved to the world that when New York gets knocked down, we always, always get back up. And because of that, I’m optimistic about this upcoming year and about the future.”

Housing

Hochul said that one of the major crises facing the Empire State, and especially New York City, is a shortage of affordable housing, with more than half of New Yorkers being rent-burdened and rents in the city having risen 30% since 2015, according to the governor’s office.

“Equal access to housing is a must,” Hochul said. “Because there’s not sufficient housing, people at all income levels struggle. And if things get bad, they leave. They search for opportunities elsewhere.”

To that end, Hochul unveiled her long-awaited plan to construct 800,000 units of new housing over the next decade, which she’s dubbed the “New York Housing Compact.”

The plan includes several policy changes, Hochul said, such as: requiring all municipalities across the state to hit new housing construction targets; opening a $250 million “Infrastructure Fund” and $20 million “Planning Fund” to help support housing construction; cutting red tape to speed up projects’ development; and creating a new tax incentive for building affordable housing to replace 421-a — which expired last year.

Hochul also proposed rezoning areas within a half-mile of train stations for increased residential development.

Under the new housing construction targets set forth in the plan, downstate areas — New York City and the surrounding areas that are served by the MTA’s commuter rail lines — will have to build new units at a 3% rate every three years, Hochul said. Upstate areas will have to meet the goal of creating 1% of new homes over a three-year period.

“Many localities are already hitting these goals,” the governor said. “But the reality is, there are some communities that need to effect real change to build the homes we need. So it’s not a one size fits all approach. Local governments can meet these targets any way they want. They can shape building capacity. They can redevelop old malls, old buildings, office parks, incentivize new housing production, or just update the zoning rules to reduce the barriers.”

Basha Gerhards, senior vice president of planning at the Real Estate Board of New York (REBNY), in a statement to amNewYork Metro, applauded Hochul’s focus on increasing housing production and developing a new incentive program for private developers.

“New York City urgently needs more rental housing, especially apartments at below market rents,” Gerhards said. “We applaud the Governor for underscoring the critical role the private sector must play in that effort through a workable incentive program, along with the importance of creating policies that encourage rental housing production.”

Progressive housing activists, on the other hand, are far less pleased with Hochul’s proposals. Cea Weaver, campaign coordinator with Housing Justice for All, said the governor’s plan consists of “handouts” to developers. Plus, she said, it lacks increased investment in public housing and a push for legislation aimed at protecting tenants like “Good Cause Eviction” — a bill that would prevent landlords from ending a tenancy without proving a tenant violated the terms of their lease.

“Instead of investment in public housing, we got handouts for big developers. Instead of vouchers to help more New Yorkers afford homes, we got zoning changes. Instead of real tenant protections like Good Cause, we got more wishing and hoping that the private market will solve everything,” Weaver said, in a statement to amNewYork Metro. “To truly solve the housing crisis, we need robust protections from rent hikes and evictions, deep investment in rental assistance, and a commitment to social housing that’s free from market forces.”

Public Safety

The governor said her “number one priority” has always been keeping New Yorkers safe, a task she said has been made far more complicated by the COVID-19 pandemic.

“The pandemic caused so much havoc in our state, our country, society, and had a profound effect on public safety,” Hochul said. “That pervasive unease that wormed its way into our day-to-day lives. The social isolation, the economic distress, led to a nationwide rise in gun crimes and violence that we’re still combating.”

Hochul said she wants to build upon past changes she championed to the state’s 2019 bail reform laws, which eliminate cash bail for most misdemeanors and non-violent felonies. She wants to accomplish this by eliminating the so-called “least retrictive standard, which compels judges to consider the least restrictive means when deciding whether to hold someone charged with a crime pre-trial.

While bail reform has become a divisive issue, she said, with criminal justice reform advocates fighting for it to not be rolled back on one side, and law enforcement agencies pushing for its repeal on the other, there are many areas where common ground can be reached.

“First, the size of someone’s bank account should not determine whether or not they sit in jail, or go home, even before they’ve been convicted of a crime,” the governor said. “Second, bail reform is not the primary driver of a national crime wave.”

“But also, I would say we can agree that the bail reform law as written leaves room for improvement,” she added. “And as leaders, we cannot ignore that, when we hear so often from New Yorkers that their top concern is crime.”

But Katie Schaffer — the director of advocacy and organizing at Center for Community Alternatives, a criminal justice reform group — pushed back on Hochul’s notion that any changes should be made to the 2019 bail laws. At the same time, she urged Hochul to instead champion criminal justice reforms like the “Clean Slate Act”, a bill that would clear a New Yorker’s conviction record after a set time period.

“As the Governor herself acknowledged, bail reform was urgently needed to address the criminalization of poverty and is not a driver of national increases in crime following the pandemic’s social and economic dislocations,” Schaffer said. “Furthermore, the “least restrictive” standard is based on constitutional protections and existed prior to New York’s bail reform legislation. We urge the Governor and the legislature to focus on community investments and policy change like the Clean Slate Act which are evidence-based means to create safer, stronger communities.”

Assembly Speaker Carl Heastie, who’s been opposed to making any further changes to bail reform, told reporters after the address that he needed to review Hochul’s proposal before weighing in on it.

Other Proposals

The governor also laid out plans for repairing and expanding the state’s mental health care system, amid a mental health crisis gripping the state in the wake of the pandemic. She said her administration is “prepared to invest” $1 billion to fund the necessary policy changes to address the crisis.

That money would go toward adding 1,000 psychiatric beds by funding 150 new beds and bringing another 850 back online, Hochul said, which will serve over 10,000 people every year. Additionally, she said, the state will also fund the creation of 3,500 supportive housing units with “intensive” wrap-around services.

“Today marks a reversal in the state’s approach to mental health care,” Hochul said. “And this is a monumental shift to make sure that no one else falls to the cracks. This will be the most significant change since the deinstitutionalization era of the 1970s.”

When it comes to the cost of living, which has been exacerbated by ballooning inflation over the past year, Hochul proposed a plan to make increases in the state’s minimum commensurate with the rise in inflation.

“As a matter of fairness, social justice, I’m proposing a plan to peg the minimum wage to inflation,” Hochul said. “If costs go up, so will wages. Our families deserve this.”