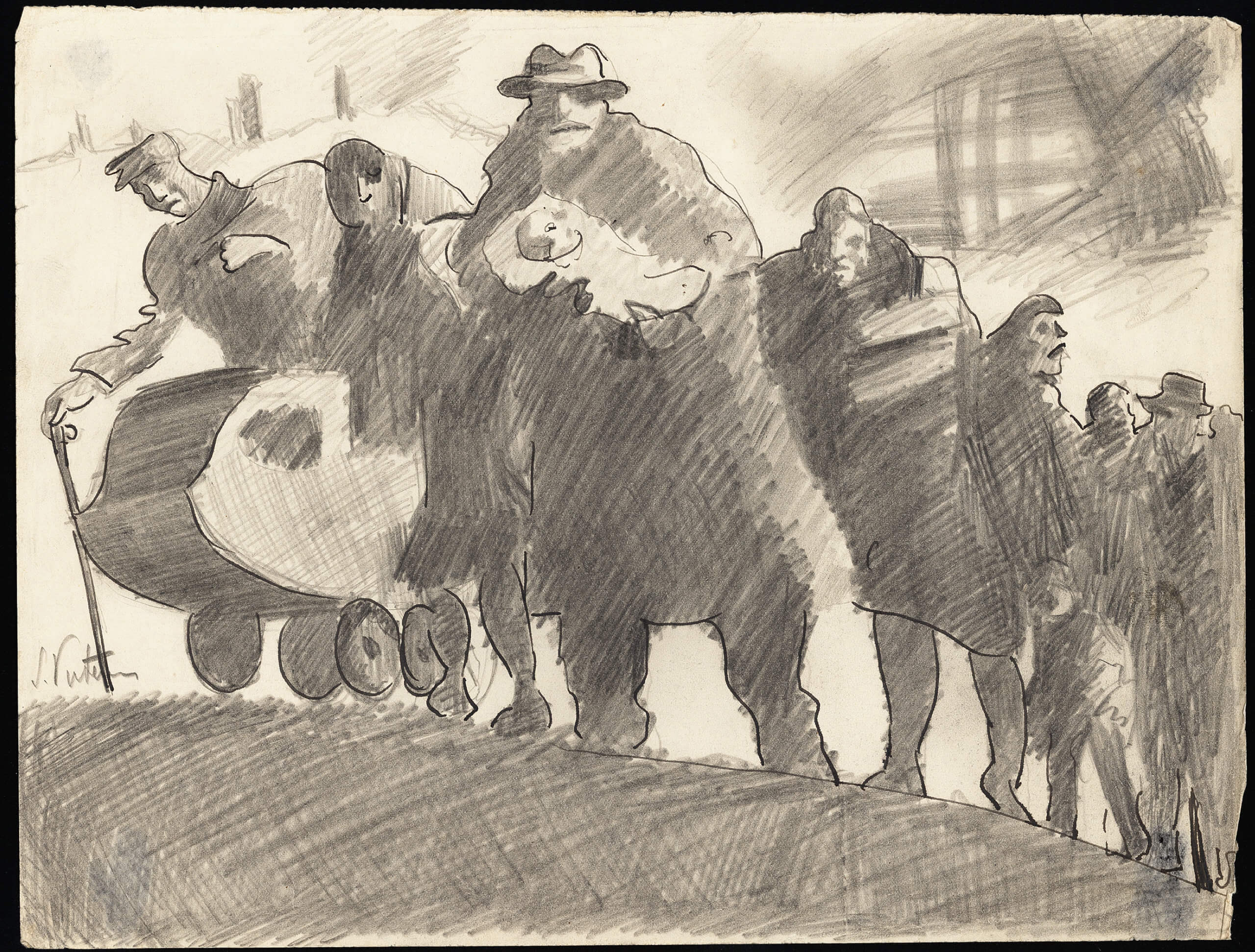

At the Museum of Jewish Heritage, small, household items connect a vast network of stories.

A kosher cooking pot, a hand-stitched blouse, a crematorium brick, a child’s chalk-scratched blackboard, a blue sheet of legal paper emblazoned with the text ‘Affidavit of Support’ for emigration — these are some of the historical artifacts that the Battery Park museum assembled to ground the terrible history of the Holocaust in personal terms.

On Tuesday the museum opened a new exhibition commemorating the Holocaust, titled “The Holocaust: What Hate Can Do,” which offers new telling of Holocaust history through a collection of many unreleased personal stories, objects, photos and film.

Museum President and CEO Jack Kliger said his goal was “reminding the world that these people existed, telling their story, showing their pictures, exhibiting their objects so that they, and what happened to them never will be forgotten.”

The two-floor exhibition features over 750 original objects and survivor testimonies from the Museum’s collection.

These items are interspersed between panels that capture the history of antisemitism that stretches back far before the Nazi Party rose to power and continues through the end of World War II. It also tries to capture what life was like for the diverse groups of Jewish people during the period of European modernization, World War I and during the initial years of the Nazi Party.

The objects, which were donated by survivors and their families, serve to explain what each stage of the holocaust meant through the lens of an individual.

A blouse worn by Rachel Porus, a young Lithuanian Jew who was killed during the “Final Solution” stage of the Holocaust outside the Vilna Ghetto provides a reminder of mass killings. But as a humanizing audio guide that provides extensive background on many of the items points out, the item was returned to Rachel’s sister Chaya, who wore the item when she later joined a Jewish paramilitary organization to fight Nazis from the forests of Eastern Europe.

The items and accompanying stories explore the values and rituals of the Jewish people. Like that of the blouse, many are a painful remembrance serving to document how racism, fascism, pogroms, ghettos, mass murder and concentration camps came into being.

They also tell stories of resilience in the face of incomparable tragedy.

“We also tried to address common myths and misconceptions about the Holocaust, which persist to this day like the myth that the Jews didn’t resist. They didn’t fight back,” said Paul Salmons, the creator of the digital guide on the Bloomberg Connects app.

For the museum leadership and board members, many of whom are related or personally connected to survivors, the mission of preserving the stories in exceptional detail was personal and urgent.

Present at the exhibition’s unveiling were several survivors. Toby Levy was born in Poland to an orthodox Jewish family that went into hiding from 1942 until the Soviet Army liberated the region. She spoke to media about how important she feels it is to share her story publicly now, given the rise in incidents of anti-Semitic violence in recent years.

She said still doesn’t have an answer as to what undergirded the antisemitic hate that she encountered in her lifetime, but her message was one of optimism and appreciation.

Once she said she was asked whether she ever wants revenge, and she responded, “I had my revenge. I am alive. I live life. I enjoy every minute of my life. I have Jewish children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren. That’s my revenge.”