BY MARIANNE LANDRE GOLDSCHEIDER | The Catholic Worker is many things to many people. Its founders were Dorothy Day and Peter Maurin.

Dorothy Day became a well-known figure. Today she is being considered for canonization as a saint by the Roman Catholic Church. Her memoir, “The Long Loneliness,” is still in print. Born in Brooklyn in 1897, she and her family moved to San Francisco and then Chicago. Her father was a sports writer.

Later the family moved back to New York City, where she became a journalist, writing for The Masses. She was part of a bohemian crowd in Greenwich Village that included Eugene O’Neill and Malcolm Cowley and Agnes Bolton, among others. This was in the nineteen teens. These were lively years; she was a lively young woman. At one point, she became pregnant. Her lover told her to get an abortion or he would leave her. She did, and he left her anyway, as is so often the case. She regretted the abortion for the rest of her life.

Dorothy then studied nursing at King’s County Hospital. In the meantime she wrote a novel, “The Eleventh Virgin.” She met a young man, Forster Batterham, who stylized himself a naturalist, though he was not a trained scientist. She fell deeply in love with him and they lived in a cottage on Staten Island, which she had purchased from having sold the rights to her novel to Hollywood.

They lived an idyllic life by the sea. She recalled in her memoir how wonderful she felt lying next to his body, smelling of sand and sea. In 1926 their daughter Tamar Teresa was born. She and Forster were not married, however.

Dorothy had always had an interest in the Bible. She grew more intensely religious. Seeking an anchor, she was drawn to the Catholic Church. She had her baby baptized a Catholic. She herself converted the following year. Forster hated religion and would not marry her. They parted but remained friends for the rest of their lives.

Dorothy now found herself a single mother and describes in “The Long Loneliness” her struggles. She lived for a while in Mexico, then in Los Angeles, writing film scripts, supporting herself and Tamar, finally moving back to New York City, living with a sister in what was then called the Gaslight District, an area later razed to build Stuyvesant Town. As a reporter, she went to Washington, D.C., in December 1932 to report on the Bonus March of veterans of World War I. This was the time of the Great Depression.

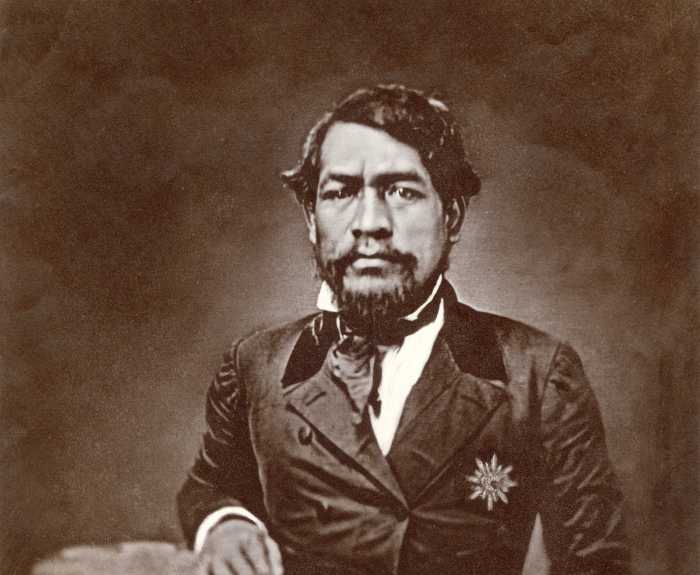

Returning to New York City, she found a guest at her apartment named Peter Maurin, a Frenchman who was 10 years older than her. Peter had been a Christian Brother teacher in Paris, who later immigrated to America by way of Canada. He was a vagabond who did odd jobs, a kind of hobo with a keen intellect. Dorothy instantly was inspired by him and his ideas to put the social teaching of the Church about economics and justice into practice by starting a monthly newspaper.

On May 1, 1933, the newspaper The Catholic Worker was launched. It sold for a penny a copy, which is the price to this day. They peddled it at Union Square.

Although Dorothy’s apartment was small, Peter said, there is always room for hospitality. He and Dorothy believed in practicing what Catholics call the Works of Mercy described by Christ in the 25th chapter of St. Matthew’s Gospel.

Their faith and dedication where contagious and soon others joined them, eager to help. Thus, the Catholic Worker movement began, dedicated to living the Gospel, helping the poor, advocating for justice and peace, favoring ownership of property for all, not just for a few, and small farms. They wanted a decentralized political order where people could be free and responsible.

Today the movement is now 81 years old, with much history, solid traditions and an appealing philosophy: Dorothy and Peter were faithful, devout Catholics. They loved the Church, yet wanted to remain independent — also independent of the state — so they never became a tax-exempt nonprofit and have never sought state funding. They declared themselves anarchists.

Well, that’s a very brief, incomplete history of the Catholic Worker movement. Here is my story.

In 1968 I was a teacher of German at Columbia University, involved with a young protester. He had heard of the Catholic Worker movement and its farming community at Tivoli, New York, on the Hudson, where he wanted to take me, and also about its House of Hospitality for the homeless, St. Joseph’s House on E. First St. In the 1970s another house, Maryhouse, was opened on E. Third St. One evening he took me to St. Joseph House, but as we lived Uptown and so much was going on in our lives, we did not return. We had no time to go to Tivoli.

Some years later I met a Spanish painter named Paco and moved to his loft on Second Avenue between 11th and 12th Streets — minutes from the old Third Street Music School, which Dorothy Day had bought in 1975 as a home for women. Peter Maurin was long dead, having passed in 1949. Dorothy Day was in her late 70s. Maryhouse is modest and barely visible. I am not a Catholic. It was not until 1991 that I first set foot inside Maryhouse, myself then a year shy of 60.

My career at Columbia had come to an end in the student unrest of the ’60s; the father of my two sons had divorced me. My sons had left New York. My artist friend Paco had moved to East Hampton. My mother, who had died in Vienna in 1982, left me a little money, enough to subsist below the poverty level. The Catholic Worker lives what they call “voluntary poverty”; I preferred involuntary poverty to tedious jobs. I became one of many poor, old, lonely women, drawn to a community that would eventually warmly embrace me.

I went to a Friday night meeting, one of a series of free, open-to-the-public lectures the Catholic Worker holds on Friday nights from September to June. Interested and fascinated by their presence in the neighborhood, I joined them.

I now lived in a walk-up on E. Sixth St., next door to the Gandhi restaurant. My rent was low, my needs minimal. (I grew up in wartime Prague). I had time on my hands. A friend had asked me to speak at a rally of the squatters at Tompkins Square; my audience was perhaps 10 people, among them a woman poet, who promised to help me publish my writings (all unpublished to this day). One day she went to see a clairvoyant, who suggested she visit the Catholic Worker. She took me along.

We were met by Jane Sammon, in many ways a successor to Dorothy Day — a wonderful and brilliant woman, who welcomes all visitors. She asked me a few questions and noticed my German accent; Jane loves Germans. This was my entree into the Catholic Worker. She gave me a copy of “The Long Loneliness.” I asked what I owed and she said, “All is free in our house.” I asked if I could make a contribution. “Yes,” she said.

I liked this house and continued coming to Friday night meetings. Roger O’Neill, a member of the community, had come to some squatter meetings. One squatter actually said to me that Roger had an interest in me; he did, but not in the way the squatter insinuated. He saw in me a congenial soul. With a lot of time on my hands, I wanted to do some volunteer work. But skeptic that I am — I had tried this and that — I decided I wanted paid work.

Roger invited me to come to St. Joseph’s House — “when the redhead is there” — and help cook for the two houses. At one time, I was also joining Women in Black vigiling for peace outside the public library on 42nd St., which they do to this day. It was the day the redhead was cooking. Still, I could help cook and join the vigiling women by 5:30 p.m.

The squatter movement of which I was a part was lively, but very different from the faith-centered Catholic Worker. Yet as the ’90s progressed, the city was cracking down on squatters more and more, evicting them from their buildings.

One day in 1997 I was at Maryhouse. A woman named Cathy Breen was there; she had spent 10 years in Bolivia as a Maryknoll lay missionary. She heard my German accent and a new chapter in my life began.

Cathy, in her friendly, outgoing way, addressed me, and we quickly found an affinity. She was new to the city and eager to make new friends. I was 65 years old by then, 15 years older than her. Many of my friends had died, and others left a New York that was no longer affordable. I saw myself in the category of old, poor, lonely women in New York. I was attracted to the Catholic Worker, where people are treated with a very tolerant kindness.

Cathy drew me in. Until then I had been coming to Friday night meetings, and also had begun coming one afternoon to St. Joe’s to help with the cooking for 80. There is cooking for those who live in the houses and their friends, a group I became part of by becoming Cathy’s friend. I once was offered keys but declined, feeling my role was too negligible.

Since there is no bell I had to knock on the broken plexiglas in the door. Sometimes somebody would come sprinting down the stairs immediately; sometimes it would take awhile. I could come for breakfast, lunch and dinner — all lovingly prepared. I’ve almost never come for breakfast, but now I come for lunch and dinner, at times with great frequency, at times with lesser. Living alone, I’m happy to break bread with friendly folk, rather than eat alone and be prone to fall into bad habits of the elderly, such as eating standing up or eating little and not regularly.

At St. Joe’s cooking is done for a group called the “guests” but their coming is restricted. For the ladies at Maryhouse a meal is served Tuesday through Friday from noon to 2 p.m.; admission is unlimited, no money is asked, no praying required. The men at St. Joe’s line up outside in the morning at 9:30 and are served soup.

Many of the people are homeless. At Maryhouse showers are offered; there is a clothing room in both houses, where donations accumulate. I am more familiar with Maryhouse. The work is done by volunteers and keeping it all running smoothly — as it does — takes managerial skills and efforts. Cathy asked me to join her in the kitchen in the mornings to help her prepare the lunchtime meal served at 11:30 to residents and guests at noon.

Until Cathy asked me to help her I found it difficult to find volunteer work that suited me; too much was rigid and demanding. At the Catholic Worker, commitment is valued. Yet those who come less regularly are also welcome. No hours are set.

Cathy, like other volunteers, also had outside paid work. She worked for an asthma project in Harlem, and also began looking for a small apartment outside the house, as many workers have done. But prices had already skyrocketed, a closet on Avenue D going for $500 a month. The many years of inexpensive housing in the area were over. When rents were cheap, Dorothy Day was able to help with rent payments until the renters were back on their feet.

In 2002 Cathy accepted an offer from Kathy Kelly, who had founded Voices in the Wilderness, to accompany her to Iraq and stay there until May 2003. Cathy fell in love with the Middle East and its people and has since spent a lot of time there.

For a while I still did volunteer work distributing the Catholic Worker newspaper. I had worked as an editor, was familiar with the layout, proofreading, copyediting. I helped manually paste address labels onto the newspaper — now with a circulation of about 30,000, published seven times a year. I immediately investigated barcoding — how most publications are sent out today — and found out it’s actually cheaper than hand-labeling.

Labeling is part of the worker philosophy, and through it I met a delightful Frenchman, Roger, a member of the Little Brothers, a Catholic religious community. In Paris, he had been a chauffeur to Jacques Maritain, the French philosopher, who taught at Princeton during World War II. Roger spent time in Dachau, the German concentration camp; he had been in Africa, and was part of the French worker-priest movement. Unfortunately, he died before too long, and I was asked to write his obituary for the newspaper.

Things in life are coming to an end, and by now it’s a quarter of a century since I, in the most informal and accidental way, joined the Catholic Worker. I have learned about its philosophy — a philosophy very congenial to me and that I have lived in many ways: Restrict your material needs to a minimum, do paid work to meet those needs, but have as much time as possible to have time — the most precious commodity. This is often maligned in corporate and academic worlds, where your greatest value is your material value, and where we cite people’s “worth” in dollars and cents.

My Harvard Law School grad ex-husband firmly believed productivity is measured by what you earn, and your value measured by the wealth and possessions you have accumulated. He accumulated a lot after he divorced me in 1967 and never shared a cent with me, telling our sons I was a lazy loser.

Coming to the Catholic Worker has given me value: the value of being a good human being.