BY LINCOLN ANDERSON

The police commander who led the raid that spiraled out of control into the Stonewall Rebellion left his assisted-living home in Whippany, N.J., for one evening earlier this month to join a discussion about the infamous event — and apologized for his role in it.

The sold-out June 2 talk at the New-York Historical Society, of which Seymour Pine was the main attraction, was part of the launch of David Carter’s new book, “Stonewall: The Riots That Sparked the Gay Revolution.”

Now 84, in 1969 Seymour Pine was a deputy inspector of the Police Department’s vice and gambling unit for the area of Manhattan covering Greenwich Village. He retired from the force in 1976.

Pine admitted that the police of the era were biased against gays.

“They certainly were prejudiced. There was no question about that,” he said. “But they had no idea about what gay people were about.”

Pine said there were two reasons why police raided gay clubs: First, many of them were controlled by organized crime.

“We weren’t concerned about gays. We were concerned about the Mafia,” he said.

Second, collaring gays was a way for officers to pad arrest records.

“They were easy arrests,” Pine explained. “They never gave you any trouble. Everybody behaved…. It was like, ‘We’re going down to grab the fags.’ ”

Raids on gay bars during his two years working in Manhattan were “very common,” he acknowledged.

At the time of the raid, the police had received a tip of the Mafia being involved with stolen European bonds. Police believed that “the after-hours clubs — like the Stonewall” were in on the operation. “If we could close them down, we’d see what would happen to the bonds that were surfacing,” he explained.

Stonewall was known to be run by Mafiosi, the former deputy inspector said.

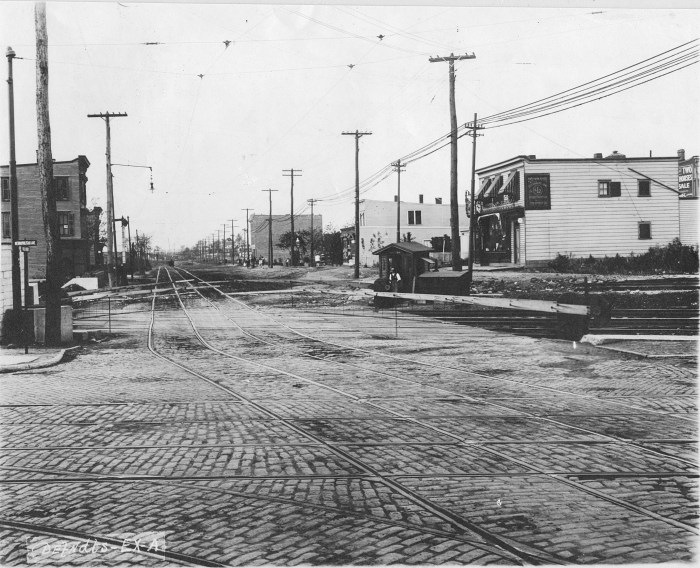

According to author Carter, the bar was opened by Tony “Fat Tony” Lauria, whose father, also a mob figure, owned a building at the corner of Waverly Pl. and Sixth Ave. But the money from the club ultimately made its way into the pocket of Matty the Horse.

Another panel member, artist Thomas Lanigan-Schmidt, one of the homeless street kids who hung out at the Stonewall, as opposed to rival Julius’s bar — which they considered too preppy — said he knew the management was unsavory. But they liked the Stonewall’s edge.

“Stonewall was where our souls could dance,” said Lanigan-Schmidt, who at the time lived in an abandoned East Village building. “It was a Mafia joint. The windows were painted black.”

Pine said limos used to pull up in front of the bar on Saturday nights, for their well-to-do passengers “to ogle” goings on at the bar.

“We never had anything to do with those people. We never had a raid when they were there,” he admitted.

There was always someone from law enforcement inside the club monitoring the activity.

“We had policewomen in there as lesbians, plainclothes cops. We even had people in there from federal agencies,” Pine noted.

The night the Stonewall riots started, there were two policewomen posing as lesbians and two plainclothes male officers in the Stonewall. They “would say who was selling [drugs], or whatever,” Pine said.

Pine and his partner, Detective Charles Smythe, were waiting in Christopher Park, across from the bar, waiting for the signal from the two female officers inside, so they could start the raid. But strangely, no signal came.

“It got to the point that either they were in trouble or they had forgotten what they were supposed to do,” Pine said.

So the officers outside went to the door, in this case, looking to bust the bar for having minors inside. They expected the homosexuals to line up docilely and march out as usual. But this night the reaction was different.

“They were acting differently,” Pine said. “When we entered, they weren’t going to go.”

According to a WBAI interview of a man who was at the riots, which Carter played for the audience, a rumor had gone out that police were holding “kids” inside the bar and beating them up.

Gays by the score began gathering outside, trapping the officers inside. This was soon followed by a hail of projectiles, from coins to more dangerous objects. At one point, a parking meter was picked up and used as a battering ram in an attempt to break the door down.

“It was very scary,” Pine said. “I had a group [of officers] completely scared. The cobblestones that were being thrown and the bottles being thrown when we moved back inside. We knew we were in trouble. I was concerned that someone wouldn’t lose their cool. If someone pulled a trigger, we were dead — because they would’ve just run over us,” he said. “They were throwing Molotov cocktails in there,” he added, “but we put that out.”

According to Pine, a female officer managed to get out through a vent in the rear and make it to a local firehouse where there was a police radio, which she used to call the Sixth Precinct for backup. But the backup took an unusually long time to arrive. Pine thinks the Sixth Precinct was taking its revenge.

“We knew the Sixth Precinct wasn’t very effective in keeping these bars properly controlled,” he said. “We didn’t tell them we were going to raid the bar, so I guess they showed us.”

Finally, after two police wagons showed up, Pine felt the coast was clear enough to make his exit.

Carter added that geography helped fuel the riots. The Stonewall is near three major avenues, six subway lines and two PATH stations. Also, perhaps further stoking indignation was the fact that Judy Garland had died that Friday.

“If I had known that Judy had died at that point, I wouldn’t have had the raid,” Pine confessed.

Audience members thanked Pine for inadvertently starting the gay-rights movement. However, journalist Andy Humm said Pine should apologize, noting, “It’s ridiculous to thank someone who ruined so many people’s lives.”

“I’m sorry!” Pine said with a grin, and throwing his arms open wide.

Pine said they continued to raid gay bars after Stonewall, but that they “didn’t wreck the place,” like they once did. When they had raided the Stonewall on earlier occasions, they’d go in with Emergency Service Unit police and cut up the bar with a chainsaw and remove it and “strip the place,” he said, making it harder to reopen. For a short period afterwards, some gay bars that served only soda opened, he added, but they didn’t last.

Lanigan-Schmidt said that the street kids, in particular, played a special role in fueling the rebellion.

“The street kids did make it happen,” he said, “because everyone else was chicken.”

Afterwards, the panel, which also included Dick Leitsch, of the Mattachine Society, an early gay-rights group, received heartfelt applause, and audience members rushed up to a smiling Pine to get his signature on copies of the new book.

Dan Pine, his son, stood watching as his father doled out autographs. He was a high school student and they were living in Rockaway when the riots happened.

“I think it’s good for him to do this — both for him and the community,” he said.

Though there were many gay activists in the crowd, not everyone was one. Christabel Gough, secretary of The Society for The Architecture of the City, came to know Carter, her neighbor on Christopher St., through his work fighting the Port Authority’s plan for new PATH train exits in the Stonewall National Historic District. Carter collected signatures from Edward Albee and about 20 other celebrities living in the area on a petition against the plan.

“I think anything that makes Stonewall better known is a weapon against the Port Authority, that wants to destroy the neighborhood,” said Gough — who lives next door to the famous bar — of Carter’s book.

At the time of the rebellion, Gough was living above the Riviera on Seventh Ave. S.

“People were in the street chanting ‘gay power!’ ‘gay power!’ ” she recalled. “I’d never heard of gay power till then.”