The dust cloud from the collapse of the World Trade Center that engulfed Lower Manhattan on Sept. 11, 2001, caused lasting damage to thousands of Downtowners, experts say, but many of them still don’t realize how they were affected, or that help is available.

BY DENNIS LYNCH

It’s been more than 15 years since the 9/11 attacks spread a cloud of toxic chemicals and dust across Lower Manhattan, and advocates say that many of the people who were harmed by it still don’t realize how they were affected — or that help is available.

Despite huge amounts of publicity around the Zadroga Act, which provides health care for those harmed by the fallout and compensates them for their injuries, there are tens of thousands of people eligible for the program who haven’t signed up for it.

An exact count of how many people could be eligible for the September 11 Victim Compensation Fund (VCF) is elusive, even to people who have spent the last decade fighting for it. One thing is certain, though — far more people were affected by the toxic dust than have signed up for the program, according to the director of 9/11 Environmental Action, a survivors advocacy group.

“At the end of the day, here’s what we know — the federal government has provided for 25,000 treatment slots in addition to everyone who was already in treatment when they passed the bill, that’s a lot of treatment slots and we’re nowhere near approaching that number,” Kimberly Flynn said.

Thousands of Lower Manhattan residents and workers returned to their homes and jobs in the weeks following the 9/11 attacks after Environmental Protection Agency head Christine Whitman falsely declared a week after the towers came down that the air Downtown was safe. These people are at risk for many of the same diseases killing first responders and other Ground Zero workers, including cancer and pulmonary diseases, according to a lawyer who represents 9/11 victims.

“It was incredibly democratic toxic dust down there, and folks were convinced the air was safe,” said attorney Michael Barasch. “I think the government is going to be a lot more careful when they have the EPA czar come out and say the air is safe, I don’t think that’ll happen anymore.”

Flynn believes that most people trusted Whitman’s false claim that the dust wasn’t harmful, and then tuned out. People moved on with their lives after hearing it was safe Downtown, and likely haven’t ever questioned if later illnesses might be related to the attacks, she said.

“When health authorities actively disconnect the dots between exposures and the resulting health impacts, people go ‘Okay, maybe this is not from 9/11’ or they go ‘I guess I’m just going to go to my private doctor and see what they recommend,’ when they could be getting specialized care from doctors who have been working on this for years and strategizing about this every day.”

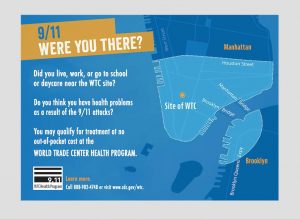

But anyone who was south of Houston St. shortly after the attacks — and many people in Downtown Brooklyn, Brooklyn Heights, and DUMBO — could be eligible for care if they have any one of the numerous conditions the federal government has now certified as related to the attacks.

The Zadroga Act, first passed in 2010 and then renewed in 2015, establishes two programs: a compensation program that expires in 2020 without a renewal, and a healthcare program that is funded through 2090. Anyone who suspects they are suffering an illness caused by the attacks — whether cancer, respiratory issues, or post-traumatic stress disorder, or any other covered condition — can start the process of making a claim with a medical exam at a local center.

The program covers dozens of cancers, numerous aerodigestive disorders — such as asthma and chronic laryngitis — and mental health conditions, including anxiety and substance abuse problems.

If certified to have a related injury, a victim has two years to make a compensation claim, which could be for pain and suffering as well as to recover past and future lost wages. If a victim has already paid out of pocket for healthcare before becoming certified, they can be reimbursed through the program.

Even a month after the 9/11 attacks, the still-smoldering wreckage at Ground Zero spewed noxious smoke and toxins into the air.

Ground Zero cleanup worker John Feal has since dedicated himself to raising awareness of the help available to those harmed by the dust and fumes from the infamous “Pile” that smoldered Downtown for weeks. He hopes that more people will sign up before they’re slammed with huge healthcare costs, which he said happens to all to often.

“Its heartbreaking. Imagine the person who lost their apartment or their brownstone because they couldn’t afford the care, and meanwhile there’s a World Trade Center clinic near them where they can be getting treated for free,” said Feal, who founded the Fealgood Foundation.

The 75-year term of the healthcare program may seem excessive for a bill meant to protect people who were mostly adults at the time, but there are indications that even the unborn children of women exposed to the dust were affected.

A study published in the fall of 2016 found that Downtown women who were in their first trimester during the attacks were twice as likely to deliver their babies prematurely and more likely to have low-weight babies. Babies with low birthweight are more likely to develop diabetes, heart disease, high blood pressure, and be obese later in life, according to the March of Dimes.

Feal recalls that cleanup crews only had to wash down the outside of their vehicles when they left the Ground Zero site, and were not required to change their clothes or wash the insides of their vehicles — so they literally brought the carcinogenic dust home with them.

“They got home and they put those clothes in the washing machine with all of their family’s clothes,” Feal said.

The federal government has not yet included complications from low birthweight as eligible for coverage or compensation under the bill, but its possible it could in the future. The Zadroga Act allocated $15 million for scientists to investigate conditions potentially linked to attacks. Anyone can petition the Centers for Disease Control, which administers the program, to consider a health condition to be linked. Recent petitions include multiple sclerosis and rheumatoid arthritis.

It’s not an easy process, though. The threshold for evidence to link a disease to the dust is high. The act “requires that there be peer-reviewed, scientific evidence that the condition is related to a 9/11 exposure,” according to Ben Chevat, who helped write the Zadroga Act and now runs the advocacy group 9/11 Health Watch. For example, it took until 2012 for the federal government to add 50 cancers to the list of covered illnesses, and it has added only 18 more in the four years since.

The Zadroga Act also helps fund the efforts of advocates such as Flynn and Feal, who work to let potentially eligible people know what conditions are covered and what help is available.

Through his foundation, Feal travels the country to educate the thousands of first responders who flocked to Ground Zero from across the nation. Flynn and her cohorts hit the streets of Lower Manhattan and go to community meetings with informational pamphlets — and if they find someone who may be eligible, they help them sign up for an examination at one of the three certified 9/11 clinics in the city.

Flynn said, and noted that folks from 9/11 Environmental Action will be posted outside local Catholic churches this upcoming Ash Wednesday.

“We’ve found that’s a really good way to encounter area workers who don’t live in the area but commute here, because Ash Wednesday is a religious day of holy obligation, so they’ll come to the church near where they work,” she said.

So, as folks leave church with their holy ash markers on their foreheads — a symbol of repentance that saves the soul — Flynn will be handing out information about treatment for the harm that 9/11’s unholy ash might have done to their bodies.

“What I want people to know is that there’s something out there for people who are suffering from both physical and mental ailments, there are many unresolved health impacts people are suffering from needlessly, and people can benefit from the program,” she said.