BY JERRY TALLMER

An old man and a young woman are walking around an invisible room, keeping count of their paces. His paces. Six paces from here to the wall, four paces to that window, five paces to the sideboard, two more paces to the radio.

“I think I can even remember the brand,” says the man. “Körnung.” From that radio he had acquired his lifelong love of music. And maybe, in faded recall: “This is the BBC, London. Tonight Herr Hitler and Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain…”

The man pacing off the “virtual” living room, as the woman calls it, is Manfred Nomburg, now in his late 80s. He left Berlin, left his native Germany, in 1938, just before Kristallnacht — a teenager making his way with other young Jews to Haifa and the Promised Land. Most of his life, we’re told, he has worked in Israel as a carpenter.

The woman interviewing him as he paces that ghost room is in her early 30s. Her name is Maya Zack, a great name for an artist. She is an Israeli, bred and born, and is indeed what might be called a conceptual artist and filmmaker. Her concept — shared with Proust, Joyce and quite a few other people — is that memory is the life’s blood of civilization. But how trustworthy is memory? And how far can you rely on it?

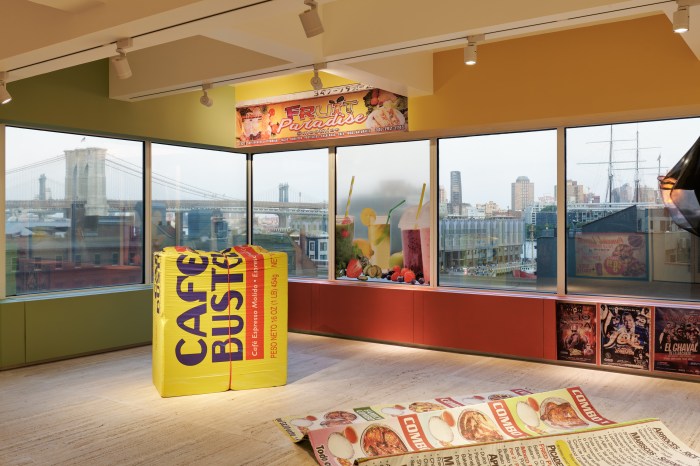

Which is why Maya Zack and Manfred Nomburg are mentally and pacingly reconstructing a 1930s Berlin apartment in a building long since bombed out of existence by Allied planes in WWII. And why this reconstruction of a German Jewish Berlin apartment in the 1930s is now open for inspection — via soundtrack and 3-D goggles — from July 31 through October 30 at our own city’s Jewish Museum.

The installation is called “Living Room.” If you want to know the truth, as Holden Caulfield would put it, the 1930s German Jewish Berlin apartment inhabited by Manfred Nombug, his kid brother and their parents sounds very much, right down to the radio, like the several Manhattan apartments — East Side and West Side — inhabited in those same years by my parents (or parent), my kid brother and myself.

But our radio — the earliest one — was an Atwater Kent.

“What I wanted,” said Maya Zack, on the blower from Tel Aviv, “was to find someone urban and German, in Tel Aviv — a German Jew. I interviewed five or six people — five men and one woman — and Nomburg was the most interesting one.”

Her own roots are “mostly Slovakian,” and a few years ago she and her father took a trip to see his sister in Košice, Slovakia — out of which came Maya’s 19-minute prizewinning documentary, “Mother Economy,” which itself had a three-month stand at The Jewish Museum.

Why had she subsequently wanted to dredge the dwelling-place memories of a Jew who’d spent his early years in Hitler-era Berlin?

“Growing up in Israel, there is always a different place that you’re related to. You always have the feeling,” she says, “that life is very fragile, very temporary.”

And you feel that?

A pause on the line. Then: “Yeah, in a way. So I guess the idea was: How do I know my own history?”

The time-and-place interview with Manfred Nomburg was conducted in Hebrew, plus a few phrases in German. It was all done in one session over a few hours. She calls it “the virtual walk.”

Almost every one of its more than 2,600 words (in English translation) is as mundane as a shopping list or a furniture-store catalogue, yet I found all of it compulsively fascinating.

Here’s a bit of it, just to give the idea:

And a clock: there was a standing clock. That was over here, I think. My father used to tie his tie in front of that clock. It was like a mirror, made of glass, so he used it as a mirror.

Here there was a large cupboard, a very large one where they kept all the — it was called a Service — all the plates, glasses, all you would need for meals. Forks, cutlery, all made of silver, such heavy silver — that is, heavy to hold in the hand. Tablecloths were kept there too — all the things you would need to set the dining table. A cabinet like that was called a Kredenz. I cannot remember how many doors it had, but I know furniture pieces like that: a set of drawers with a marble top, usually, or some other material of that sort, and above that another shelf or two…

On that Kredenz cupboard, I can imagine there were Shabbat candlesticks, two of them. And there might have been a Hanukkah lamp too…

And here, couches — a sofa that I believe seated two and a couch for one, quite heavy. And a large couch, double the size, but surely with the same fabric, I can imagine it looked quite similar. The upholstery was in a light color, with flowers. People would sit there to read the paper, or if there were guests then they sat there, or after a meal they smoked, talked… So, there were invitations to my grandmother, uncles, aunts and maybe friends. I remember I had an uncle who came by, he was an old bachelor. My mother invited him often on Sundays, not on Shabbat but on Sundays, for lunch. After the meal he would sit on the couch and start falling asleep, snoring a bit. My brother told me that once he saw him with his mouth open — “Oh my God! Uncle Kurt died!” Ha ha…

Here the windows were a bit curved, well, not really round — they had angles and stuck out on the outside. There was this narrow window and here three big windows, really big. That’s the window my father liked to look out of, observing the street…

When all the elements of that domestic setting are fed by Ms. Zack into a computer — which is how artists work these days, a lot of them — “the project [becomes] no longer about a particular apartment but about memory as a virtual domain of existence — a difference in time and space between the way he says it and the way I understand it.”

Or, at third hand, the way all the rest of us understand it. Virtually, non-virtually, whatever.

Can a computer invent a chair? Like those richly brocaded chairs of Manfred Nomburg’s youth? From scratch, I mean — out of thin air?

“No,” said Maya Zack, with no detectable amusement. Chair or no chair, virtual or non-virtual, she supplied a few basic details about herself. Born May 14, 1976, in Tel Aviv. One sister. Father a lawyer. Boyfriend a Dutch filmmaker. Next project: a documentary about Yiddish.

And Manfred Nomburg’s father, who used to tie his tie in front of that standing clock, and spent hours at that window, looking down into the street, waiting, as it may be, for the Brown Shirts… What ever happened to him and Manfred Nomburg’s mother?

Verschollen — that’s what it said on the death list from Lodz, Poland. Verschollen — missing. That’s all that Manfred Nomburg would ever know about the parents with whom he lived for some years of his youth in a big, old-fashioned third-floor apartment in Berlin, Germany, in the 1930s.