More than two years after the murder of Karina Vetrano shocked the tight-knit Queens community of Howard Beach, the man convicted of her murder was sentenced to life in prison without parole.

An avid runner, Vetrano had gone out alone for a jog on Aug. 2, 2016, and never returned home. Her battered body was found hours later in a marshy area of Spring Creek Park. She had been sexually assaulted and strangled, police said.

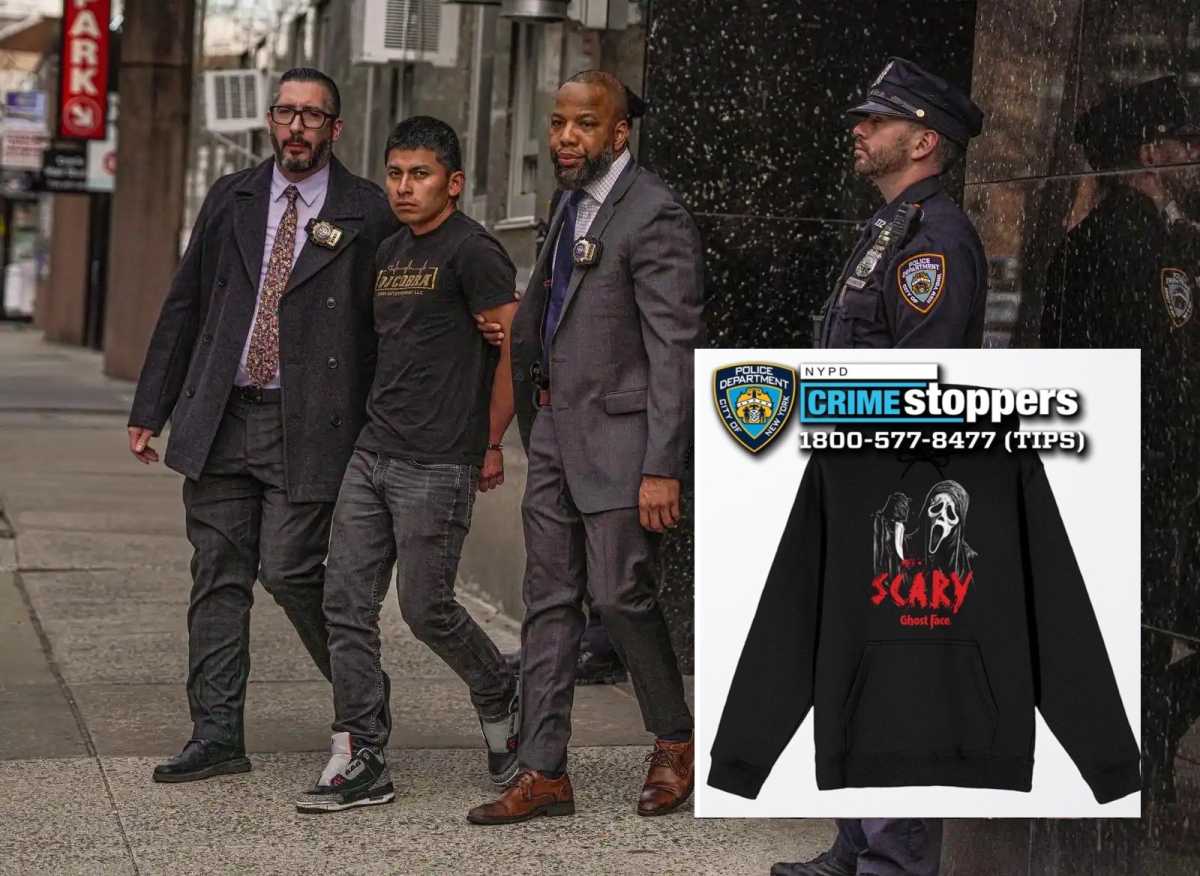

In February 2017, more than six months after Vetrano’s death, investigators arrested Chanel Lewis, then 20 years old, and charged him with second-degree murder and sex abuse. His first trial ended with a hung jury and the judge declared a mistrial in November.

Lewis’ retrial began in March and ended April 1 with a guilty verdict. He was sentenced Tuesday to life in prison without the possibility of parole. His attorneys tried to toss the verdict over claims of jury misconduct, but a judge on Monday denied the motion.

Here’s what you need to know about the retrial, Lewis, the allegations against him and more.

What did the jury find Lewis guilty of?

After five hours of deliberations, the jury found Lewis, now 22, of East New York, guilty of first-degree murder, second-degree felony murder and first-degree sexual abuse.

How did the courtroom react to the verdict?

Vetrano’s parents, Philip and Catherine, hugged as many in the courtroom cheered and cried. NYPD detectives who worked the case and testified during the trial hugged and slapped each other on the back, as did prosecutors.

Lewis said nothing before being escorted from the courtroom and his Legal Aid Society lawyers were silent as they left the Queens State Supreme Court building.

What happened in the first trial?

After one day of deliberations, the judge declared a mistrial when jurors said they were unable to reach a verdict — a decision that drew criticism in the media for its hastiness. Vetrano’s parents were solemn and did not comment as they left the courtroom following the mistrial.

The jurors were split 7-5 in favor of conviction, according to sources familiar with the deliberations.

Before the mistrial was announced, the prosecution and Vetrano’s parents also agreed that such a divide among the jurors would not be resolved with further deliberations, law enforcement sources said.

A note nearly derailed prosecutors in the retrial

Days before the jury was set to deliberate, an anonymous note was sent to prosecutors and Legal Aid Society lawyers alleging that cops targeted Lewis because he was a black man from East New York.

The letter, which made arguments sympathetic to the defense, was allegedly written by a cop and made claims about the investigation, a number of which were false based on court evidence and the NYPD. The note gave opinions on alternate scenarios as to how Lewis’ DNA might have found its way on to Vetrano’s cellphone at the crime scene.

Lewis’ attorneys moved for the judge to reopen evidentiary hearings or order a mistrial because of the anonymous letter, but the judge rejected the requests.

Did Lewis confess to killing Vetrano?

Lewis confessed to attacking and strangling Vetrano in two videotaped statements that were presented as evidence by prosecutors at both trials.

In one of the taped confessions, Lewis said he was angry over an unrelated issue at home when he encountered Vetrano in the park and lashed out at her.

The defense maintained that Lewis’ confessions had been coerced.

What about DNA evidence?

DNA evidence lifted from Vetrano’s body and cellphone, which a forensic expert said matched Lewis’ genetic profile, was presented at both trials. Police said Lewis voluntarily gave his DNA to investigators.

The defense attacked the testimony of the prosecution’s DNA expert from the medical examiner’s office, claiming she was evasive or refused to give straight answers about whether DNA could be transferred to a victim by someone other than the defendant.

With Newsday, Alison Fox and Nicole Brown