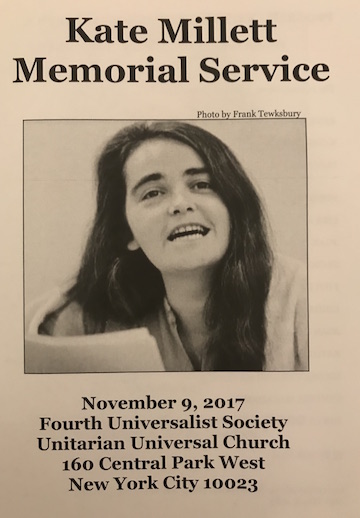

Millett died of a heart attack in her beloved Paris on Sept. 6 at age 82 on a visit there with her spouse, Sophie Keir, her partner for 39 years.

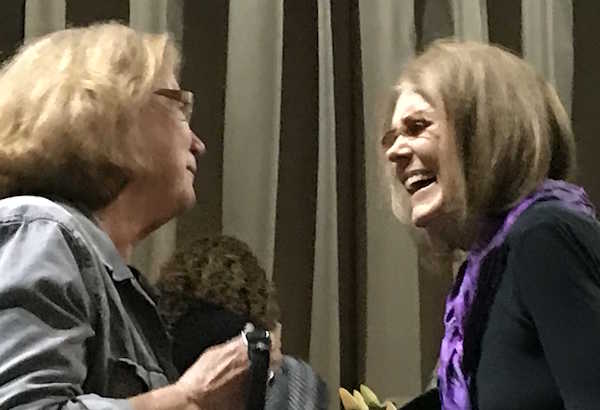

“Don’t you wish we could read Kate on Harvey Weinstein?” said Gloria Steinem, 83, to gales of laughter in the Unitarian Church on Central Park West.

The service was attended by many from the feminist movement instrumental in changing the status of women radically 50 years ago, an achievement not without a corresponding massive resistance then that continues to this day with the Trump backlash. In January, Millett, in a wheelchair and holding a sign with her name on it, was at the head of the historic Women’s March in New York against Trump the day after his inauguration — one of many dozen demonstrations that turned out masses in cities throughout the country and around the world.

Steinem recalled reading some of the material that became “Sexual Politics” and thinking, “Is it possible that a female American human being could be a global intellectual?” Such was the power of Millett’s Columbia University thesis that became an improbable bestseller and culture-shifting manifesto.

An uncharacteristically unsmiling Millett was pictured on the cover of Time magazine in August 1970 as “Kate Millett of Women’s Lib,” the kind of fame that made her uncomfortable in a movement that she saw as only succeeding based on collective efforts. In December that same year, the center-right Time played up Millett’s bisexuality to tear her and the movement down — something some skittish feminists like Betty Friedan played into (later labeling lesbians in feminism “the lavender menace”). But lesbians such as Barbara Love and Ivy Bottini staged a show of feminist solidarity with Millett that included Steinem, who said at the service, “She let me hold her hand at the press conference and we got to be an item for two weeks.”

Yoko Ono, who met Millett as a sister artist, said, “Her smile was not the kind you see on anyone else. It was part of her body and beautiful.”

Lisa Millett Rau, now a Philadelphia judge, said, “We knew Aunt Kate as an artist first, sitting on the floor with us, doing art, and talking to us like adults.” She added, “If there was a bully around, Kate would go after them,” including a perilous mission to Iran after the Islamic revolution in 1979 when Iranian feminists invited her to a women’s conference there.

Eleanor Pam of Veteran Feminists of America, which sponsored the service and that Millett co-founded, recalled her “intimate sparring partner and friend,” how when they lived on the Bowery “Kate embraced downward mobility,” and how Millett “fell in love easily and often.”

When Millett did make decent money from “Sexual Politics,” she plowed it into a farm in Poughkeepsie that became a women’s art colony known as Kate Millett Farm. Many of the feminist activists and artists who frequented it over the decades came to celebrate her at the service.

Lesbian feminist Linda Clarke called her friend of 50 years “an improbable celebrity who was first an intellectual and a bookworm.” She called her someone “who changed the world, all the while doing it with an unruly mind.”

Cynthia MacAdams, the photographer famous for capturing images of Second Wave feminists in their early revolutionary days, called Millett “a great teacher, a great lover, and a great artist… Be a warrior as Kate was.”

Kathleen Turner read a brief tribute from Hillary Clinton and a longer one from Millett’s longtime comrade Robin Morgan that included this exhortation: “A feminist generation is marching again, this time into shadow. Another generation will march into the sun.”

Holly Near led the assembled in the women’s labor anthem “Bread and Roses” and “Singing for Our Lives,” which she wrote in the wake of Harvey Milk’s assassination in 1978 — reminding us “we are a gentle, angry people and we are singing for our lives.”