Churchill Downs ran the Kentucky Derby on Saturday in the shadow of seven horse fatalities on the track – including two that occurred during undercard races.

Any horse fatality on the track, either in racing or training, is one too many. When they occur in bunches like they have at Churchill Downs this past week, many wonder how this is allowed to happen, and why they even run horses for sport in this day and age.

Naturally, the rash of deaths made Mage’s victory in the 149th Kentucky Derby somewhat bittersweet. Attached to most mainstream headlines about Mage’s victory were notes about the rash of equine fatalities at Churchill Downs. A little unfair, yes, but also unavoidable.

Horses are blessed to be among the fastest creatures on earth; thoroughbreds can sometimes reach 40 mph at the peak of their speed. Yet these majestic animals run on legs and hooves that are incredibly fragile, and a severe leg fracture can (and often does) prove fatal.

The Jockey Club notes that today, the equine death rate among American thoroughbreds stands at 1.25 per 1,000 starts – that 0.0125% of the time. Again, while one horse death is one too many, the glass-half-full side of that figure is that 99.875% of the time, these animals race, survive and live long, healthy lives.

Statistics do not assuage the anguish of the times when a horse fatally breaks down, especially on a major stage of racing like any of the Triple Crown race days or the Breeders’ Cup.

The worst moment might have been Barbaro in the 2006 Preakness Stakes. The dominant Kentucky Derby winner suffered a fracture in the early stages of the Preakness, and was pulled up to the horror of the Pimlico crowd and the millions of other fans watching around the world.

His owners – H. Roy and Gretchen Jackson of the Lael Stables – made a valiant effort to save him when, in past years, they could have easily euthanized the injured colt. Instead, they fought to save his life. Barbaro’s broken leg healed, but while he was on the road to recovery, he contracted the hoof infection known as laminitis – which ultimately proved fatal.

Safer surfaces, doping crackdown, fewer starts

Despite calls by PETA and other animal rights groups for the sport’s abolition, the horse racing industry has, in many ways, evolved for the better in the 17 years since Barbaro’s breakdown. With an entire multibillion dollar industry on the line, it had no other choice but to evolve.

Tracks around America have installed synthetic surfaces like Polytrack or Tapeta which are designed to help reduce the amount of shock a horse absorbs in full flight. The New York Racing Association is about to install such a synthetic track at Belmont Park in its upcoming track renovation, providing another, safer racing surface during all types of weather year-round.

The recently-created federal Horse Racing Integrity and Safety Authority is also working to combat the doping of equines, curtailing and eliminating the use of medications that put the health of racehorses at a higher, more fatal risk.

Racing circuits have also acted quickly to root out problems or scrap racing cards altogether out of abundances of caution. The Stronach Group and 1/ST Racing were quick to temporarily halt racing at Santa Anita Park in 2019, and at Laurel Park in April, after a rash of equine fatalities. They investigated and made the necessary safety improvements to the track before deciding to reopen them.

Trainers and owners of horses are also not running them as frequently. The best thoroughbreds in America run a handful of times every year; last year’s Horse of the Year, Flightline, ran and won just three times: the Metropolitan Mile at Belmont Park, the Pacific Classic at Del Mar, and the Breeders’ Cup Classic at Keeneland. All three starts were spectacular.

Still, there are too many reckless owners and trainers in the industry who think only of dollar signs and not of their horses’ well-being. They will dope their horses or attempt to enter them in races when they are unfit.

For example, trainer Bob Baffert, who led American Pharoah and Justify to Triple Crown victories, was subsequently busted after his 2021 Kentucky Derby champion Medina Spirt tested positive for a banned substance. Medina Spirit was disqualified as the Derby winner, and Baffert was barred by Churchill Downs for two years.

There’s no bigger name in horse racing today than Baffert, and yet, even he could not get away with violations of safety protocols. The fact remains, however, that there will be other trainers and owners who will be caught cheating — because in sports, regardless of the theatre, there will always be somebody trying to get the edge over their competitors while either bending or breaking the rules.

More triumph than tragedy

So it’s important, at this moment, to have some perspective. Yes, there has been lots of tragedy in horse racing, just as there has been tragedy in other sports. Yet those moments are far outnumbered by moments of glory and goodwill.

We’ve seen that just in the last 17 years with American Pharoah, the first Triple Crown winner in 37 years; Zenyatta, the first mare to win the Breeders’ Cup Classic in 2009; Rachel Alexandra, the super filly who won the Preakness and Woodward Stakes that same year; Flightline, whose raw speed was compared with the great Secretariat last year; and Cody’s Wish, the champion miler whose bond with a young boy with a life-threatening disability is one of the most inspiring sports stories of the last two years.

Even the outcome of this year’s Kentucky Derby, amid the tragic loss of seven horses over the preceding week, was inspiring. Mage gave a huge victory for his trainer Gustavo Delgado, a native of Venezuela; and his rider, Javier Castellano, who won his first Kentucky Derby after 18 failed starts.

But as long as clusters of horses die on the track, bad press and feelings will continue to envelop horse racing in America. So it behooves the horse racing industry to continue changing for the safer and the better.

The fatality rate will never get to zero, but getting it as close to zero as humanly possible will allow the sport of kings to thrive for centuries to come.

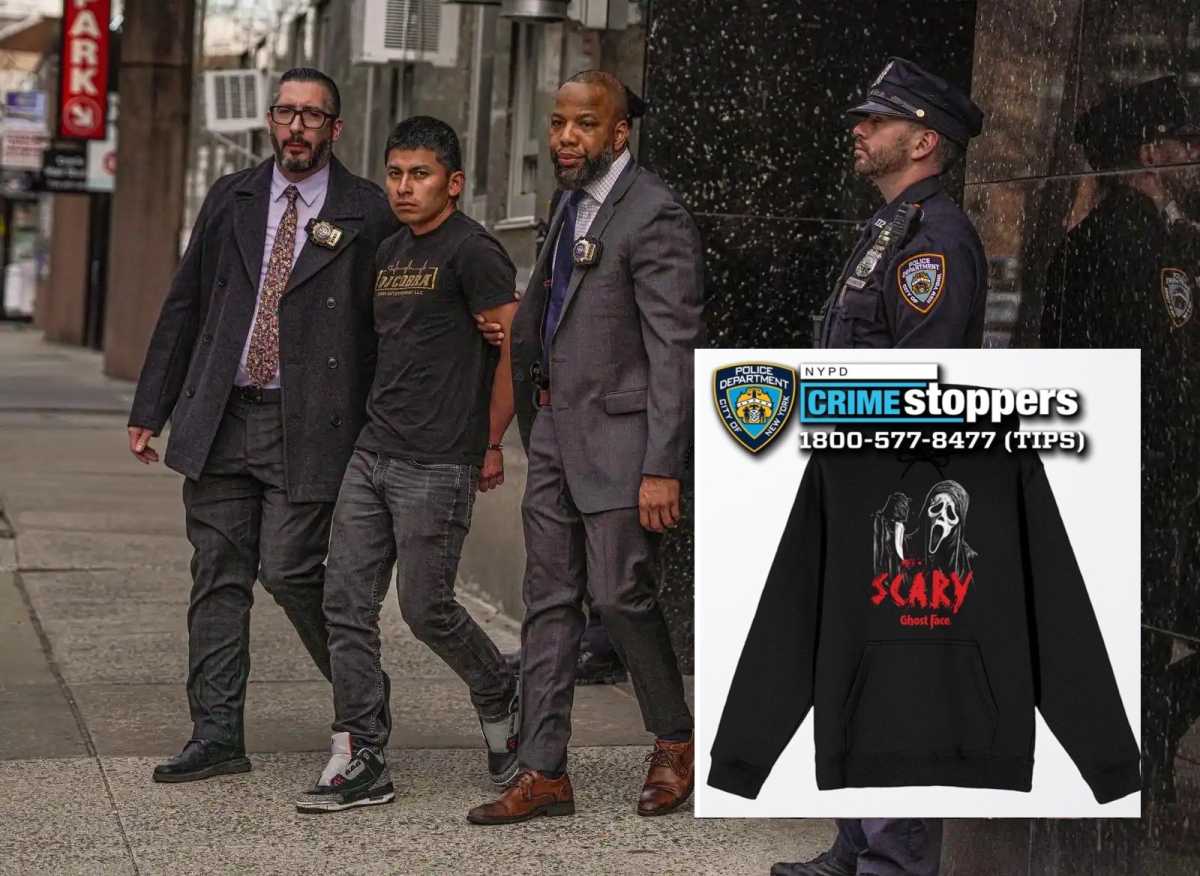

Read more: Brooklyn Apartment Fire Claims Lives; Investigations Ongoing