Time is running out for New York City co-op and condo owners to upgrade inefficient, fossil fuel-burning heating and cooling systems as mandated under city Local Law 97 — or face stiff penalties.

Many co-op and condo owners are fretting about the implementation of the climate legislation, due to take effect in January 2024, since the penalties could potentially lead to a spike in assessments. Furthermore, costly retrofits that might be required in order to comply with the law are also likely to lead to higher assessments.

Under the rules, buildings 25,000 square feet or more must meet new energy efficiency standards and comply with greenhouse gas emission limits by 2024, with stricter requirements going into effect in 2030 and getting tougher through 2050. In most cases, the rules will require building owners in coming years to replace oil and gas boilers with electric heating systems.

Most residential buildings are already in compliance with 2024 targets, with 21% not meeting these standards, according to PlaNYC, the city’s strategic climate plan that was released in April. However, that number will jump to 85% by 2030 as the stricter standards kick in.

But as amNewYork Metro outlined in the first installment of “The Costs of Change” series, older co-op buildings — unlike modern condos — are struggling to meet the 2024 and 2030 targets, mainly for economic reasons. Retrofitting their heating and cooling systems come at great costs, as do the financial penalties of failing to meet Local Law 97’s precepts.

Either way, such costs could not only jeopardize the financial stabilities of co-ops and condos, but would also be borne by residents through higher common and maintenance charges.

Editor’s note: This is the second installation of a multi-part series on Local Law 97; Part 3 will run on Thursday, Aug. 3.

‘You’re talking anywhere from $20,000 to $25,000 per family’

Warren Schreiber, board president of a 200-unit coop known as Bay Terrace in Queens, said the cost to retrofit the co-op development will be high. He said it would cost approximately $4 million to be in full compliance with the law and avoid penalties in years to come.

“We have 16 buildings, and within those buildings, we have 16 boilers,” he said. “In order to meet the requirements without paying a penalty, we would have to replace our boiler systems.”

The cost falls on the individual coop unit holders. “You’re talking anywhere from $20,000 to $25,000 per family. That’s a lot of money.”

To cover the cost, Schreiber estimates that shareholders would see a 30% maintenance increase.

Meanwhile, Bob Friedrich, president of the board of directors at Glen Oaks Village in eastern Queens, said it would cost $50 million to convert the 2,904-unit development that he oversees to be fully electric. The work, however, would not need to be done immediately but in years to come as the emissions standards get stricter.

Friedrich said the development, if it were to make no changes, would face fines starting at $394,000 each year—the equivalent of about $140 per unit—starting in 2024. The fines would jump to $1,500,000 per year in 2030 as the emissions standards get tougher and continue to increase. He said by 2050, as the fines get steeper, the penalties would total $38 million.

The ticking clock

With the January 2024 deadline just 5 months away, and another milestone approaching in 2030, building owners will have to get to work soon.

Jessica Tusing, the director of compliance at Argo Real Estate, a Manhattan-based property management firm that oversees about 120 residential buildings across the city, said that the longer co-op and condo boards leave it to do the work the worse the penalties will get.

“Let’s just say in 2024, you fix your boiler in October. If you leave it until then you are already getting penalties that won’t go away until 2025,” she said.

“Many co-op boards think they can do these energy projects last minute and that’s not how it works.”

Tusing said that six of the buildings Argo oversees are not in compliance with 2024 requirements and work is being conducted. She is currently advising co-op boards that are not in compliance with the stricter 2030 requirements to start doing the work now.

Some projects, such as removing boilers, are difficult to do in winter months, experts say, since that is when they are needed.

Thomas Ostrowski, who is a co-op board president at a building on East 4th Street in Manhattan, said that “the trick for almost every building, rich or poor, is to get beyond the 2024 cap, and then start looking at how you tailor you protects toward 2030 and then 2034 and then toward total electrification.”

“I think it is important to remember that they are giving us a pretty long time. They’re giving us like a generation.”

He advised boards not to “freak out” but to “think about what you have to do in interim steps.”

Loans are an option

Many co-op and condo boards strapped for cash are being advised to take out loans, and apply for grants, to complete the work.

The city has established a program — known as NYC Accelerator — dedicated to helping property owners find grants and loans to fund the upgrades.

The loans, officials say, would provide building owners with the ability to spread the cost of the work over an extended period, with the energy savings from the upgrades helping offset the cost of the debt. Furthermore, they say co-op boards need to upgrade their energy systems every 10 to 15 years in any case—as part of regular maintenance—and that too comes at a cost.

However, some boards are not inclined to take on any new loans on top of their existing debts.

“They tell us, we’ll give you loans, low interest loans,” Friedrich said. “I am accountant, and I can tell you we don’t need more debt. That’s a recipe for disaster and many coops have already maxed out their debt. You add debt and you are creating financial instabilities.”

Co-op boards turn to legislators

Friedrich is looking for help from lawmakers to delay the 2024 compliance date.

He supports a bill introduced by Council Member Vickie Paladino, a Republican who represents northeast Queens, that would postpone the implementation of the law for seven years.

“Local Law 97 must be delayed,” Paladino said on June 20, while co-hosting a packed meeting at a school hall in Douglaston, Queens. “There is no other way around this. This is a direct attack on the middle class.”

“We are not ready for Local Law 97,” the lawmaker told the 450 attendees at the meeting. “We need time to catch up.”

Paladino’s bill, Intro. 913, was introduced in February and currently has nine sponsors — well short of the 26 Council members needed to pass it. The chances of the bill passing are small, since the progressive-leaning Council is unlikely to consider changing Local Law 97.

In fact, several council members held a rally outside City Hall earlier this month calling on the mayor to make sure that Local Law 97 is implemented on time. They are also demanding that the city doesn’t weaken the law.

“This year has shown the climate crisis is accelerating,” said Brooklyn City Councilmember Sandy Nurse at the rally. “We need to ensure that there are no loopholes.”

The rally came just weeks after wildfire smoke blanketed New York in an apocalyptic orange haze and soon after a flash flooding deluged the Hudson Valley.

Council Member Linda Lee, who is a co-sponsor of Intro. 913 and a Democrat who represents eastern Queens, said Paladino’s bill would also provide time for the City Council to figure out alternative solutions.

“This will buy us some time, so we can work on some amendments,” Lee said. “We don’t want to displace middle class families and seniors — since many may not be able afford to live here anymore.”

“The cost to upgrade many co-ops is going to be extremely expensive,” Lee added, who noted that her district has the largest number of coops and condos in the city. “The average coop in this district is maybe $300,000 to $500,000 and then there a lot of seniors and families, with many buying them years ago for under $100,000.”

Lee said that she is tackling the issue from a number of angles.

She introduced legislation in May, Intro. 1037, that calls for exempting garden apartments that are no more than 3-stories high. The bill has 2 other sponsors.

She is also contemplating introducing legislation that would carve out coops and condos entirely, or at least buildings occupied by low-income residents.

“We’re just trying to figure out, how do we go green, but phase it in so it’s not on the backs of these people. We need time to figure it out,” Lee said.

Lee also said more needs to be done to notify unit-holders of the change and its likely effect on their assessments and costs, particularly in 2030 and beyond. She said that the upfront costs are burdensome.

‘Wish there was a carve-out’

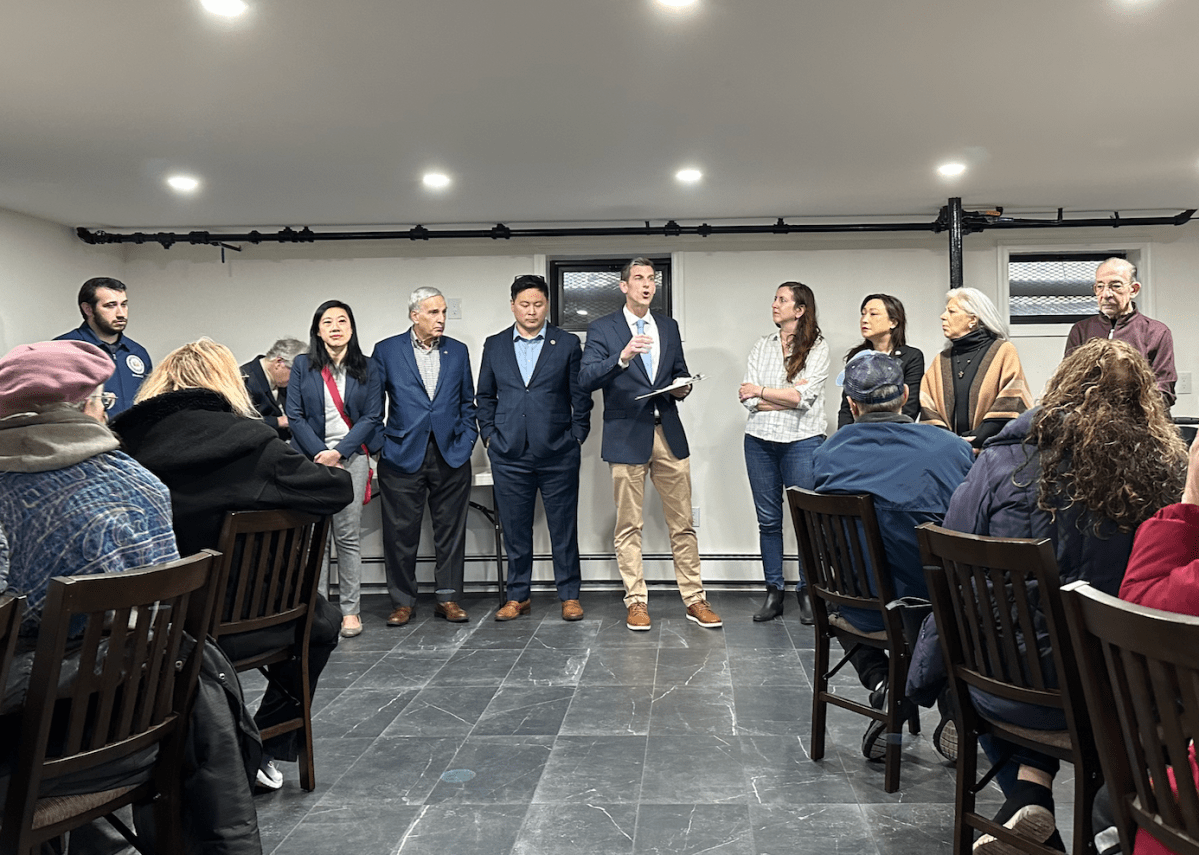

Meanwhile, Council Member Julie Won — who attended a Wednesday meeting in Sunnyside, Queens attended by 200 concerned co-op owners — is also considering introducing legislation aimed at reducing the burden for low-income unit owners.

“I wish there was a carve-out [for co-op and condos] built into the original law,” Won said. “We’re going to be introducing legislation that focuses on phase-ins for the fines and fees that aren’t so punitive — because it should be based on their income, Won said.

Lee said she is also working with Queens Assembly Member Edward Braunstein on a state bill that would provide many co-op and condo buildings with tax abatements for capital improvements that help owners comply with Local Law 97.

Braunstein, who introduced the bill in February, said that coops are a gateway to the middle-class. The bill has been sponsored in the state Senate by Brooklyn’s Kevin Parker. The legislation, however, has failed to leave committee in either chamber.

“I’ve heard from many of the co-op boards and their leadership that the implementation of Local Law 97 is going to be very financially burdensome on these co-ops,” Braunstein said. “So I am working on legislation to provide a property tax abatement for those shareholders. They’ll receive a property tax break and it’ll help offset the costs of the upgrades.”

Lee said that that there seems to be momentum for Braunstein’s bill and that she plans to push the city to support his bill and introduce a resolution before the city council.

While the resolution would not be binding, she said “it would give it a little bit of an extra push and be helpful.”

She said the tax credits would go a long way, noting that many loans would still be burdensome. “Loans are loans, and they still have to be paid back,” Lee said.

“I think it is really important that we move in the direction of protecting the environment,” Lee said. “I’m just trying to figure out the best way to get there without displacing a lot of the working and middle income class. We don’t want them to have to move out.”

The third part of our “The Costs of Change” series will run Thursday, Aug. 3.

Read more: Brooklyn Diocese faces nearly 600 lawsuits under Child Victims Act