BY MOLLY GIVEN

‘The Secret Garden’ is one of those stories that is so timeless and so poignant, that over the course of a century, the classic tale has been remade for both the screen and the stage more times than most can count. However, in Marc Munden’s latest version of the tale adapted by Jack Thorne, the story does feel a bit updated—but in a way that teaches both children and adults.

2020’s ‘The Secret Garden’ still showcases the classic story written in 1911 by Frances Hodgson Burnett, but also throws audiences right front and center into the mind of the children’s characters who create and manifest the magic of the story. In doing this, the new adaptation offers the themes we all know and love in a more heightened and sensory elevated way. This required a fresh new point of view, a lot of searching for the perfect backdrop and also the willingness to believe that sometimes we all can learn from people or places we don’t expect.

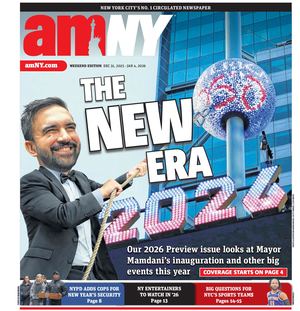

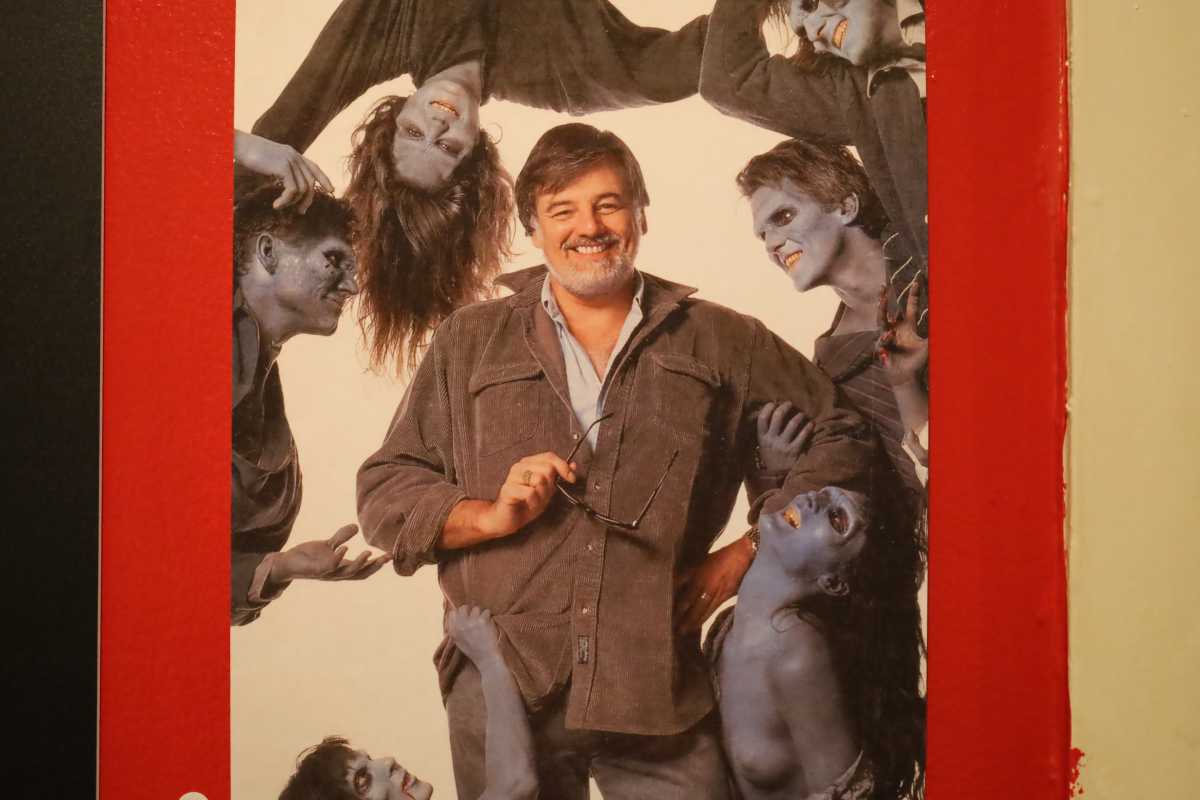

Director Marc Munden sat down with Metro to discuss what went into making the film.

What was the initial appeal for you to want to sign on direct the new remake of ‘The Secret Garden’?

I had just finished a project with Jack Thorne, the writer for a piece on Hulu called ‘National Treasure’—it’s quite dark, and a drama. When he said he was writing ‘The Secret Garden,’ I was like well, maybe this is interesting because I’m known for doing quite dark, quite odd, quite idiosyncratic dramas and I’ve never done anything for a family audience before.

Then, I really enjoyed the script that Jack had written, I thought it was the best script I had ever read. It was funny and odd and it has quite a dark story to it within some great hope and redemption, but it’s really about neglected and unloved children. I just thought, ‘Oh, I think I can bring something to this from my past experience that could make something sort of interesting, so why don’t I try and make a family film?’ And who better to make it with than Jack Thorne? Jack’s writing is wonderful and I thought the way he wrote for children felt very unique and funny and odd. They’re sort of written like adults and there is an emotional maturity about them, which allows them in the end to teach the adults a lesson.

What were you looking for when casting the children’s characters specifically?

The way that Jack writes, it really required someone who would get the language. We weren’t looking for children who were going to play versions of themselves—they have to be able to get this dry humor, we were looking for kids who were quite mature. In the case of Mary Lennox, that character had quite an arc. She starts off as this traumatized and sort of obnoxious little girl who is quite curious and gradually, she’s finding friendships with Colin and Dickon and she’s able to be selfless and show love. The friendship becomes something that helps Colin heal—helps him walk and reunites him and his father.

With Dixie (Egerickx), she’s a totally remarkable little girl. She had to be able to understand that and be able to make sense of the language, and she is really mature, you can talk to her like an adult. But at the same time, she had to play as well and she had that charm about her. She combined those two things well—being a child and having that understanding and [being] able to situate it all emotionally, we were lucky to have her.

And Edan came completely fully formed and with that funny little 1940s British accent—that’s not his accent by the way. He came building that character, but again he was young enough to be able to play as well and [had] this charm. So they each came with their own personalities, but they were also able to inhabit those characters in a way that children are not normally able to, I think. They had just such an effect on the crew as well—just well behaved and fun children, it was a really happy set.

You did spend a lot of time looking for the garden and didn’t want to create it on a back lot of a studio. Why was that so important for you?

My pitch was really to try and update it to make it something a bit more immersive and a little bit more into the garden as an extension of the children’s imagination. Just to make that connection that they were experiencing in a slightly more fantastical way. I just wanted it to be more than the past versions and for the garden to be boundless. I wanted to use the landscape of the UK because we have so many different, brilliant and natural gardens and areas from Cornwall, which is where we filmed. I wanted to harness all those landscapes and put them together in one single world, so the garden is sort of an amalgamation of all of those parts of Britain. I wanted to combine all those bits but still stick to a form of naturalism, which was heightened even more on-screen with visual effects so we all become part of the film. It felt that it was the right thing to do to have it in a natural landscape.

Overall, what do you hope audiences take away from the film?

The book itself is really about healing—healing through emotions, and I think this film has that as well. The one new thing we have in the film is the idea of adults learning from children, and that feels fresh and new. I think it’s a film filled with hope that comes from quite a dark place and Colin Firth’s character, Archie, is sort of rested in his grief and is not able to move on and with his son, and [he] is coming to realize.

So, it’s about those adults learning and children learning that they actually are loved. I think it’s about parents learning from their children and [it’s] also about getting dirty and enjoying nature. Hopefully, it inspires a bunch of children to roll in the mud—I’m sure their parents will be thanking me for saying that, but also the value of helping people and the value of friendship. So it’s got the redemption from the book but also what Jack wrote, children teaching adults.

‘The Secret Garden’ will drop on PVOD Aug. 7.

This story first appeared on our sister publication philly.metro.us.