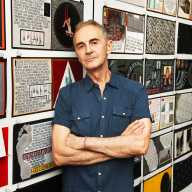

“At age six,” Mark Kostabi declares, “I instantly got a lot of positive feedback for my drawings of dinosaurs and computers. It was then that I felt that art was my calling and my career.”

He officially moved to NYC in 1982, making his home (briefly) at the McBurney YMCA. “It was $14 a night,” he recalls. “But I only had $100, so that didn’t last too long.”

Kostabi found an Upper West Side studio sublet that he could afford with the help of his girlfriend, who had a bookstore job. He scraped by selling his drawings (for $20 each), many of which went to collectors like Norman Lear and Billy Wilder, through a gallery back in California. He began to show up at group shows in Soho and then had his first solo exhibit in the Limbo Lounge.

Now living in Hell’s Kitchen, he hung out in the East Village and went to all the shows.

“East Village art in the 80s got a lot of press,” he notes, but “it wasn’t a movement, it was a scene.”

Galleries were looking for canvases rather than drawings and Kostabi switched gears and began to succeed with his. “The Kostabi World phenomenon began in 1985,” he says.

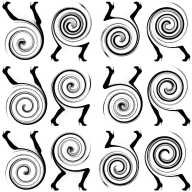

He began to hire assistants, a practice that he has taken some heat for but has no problem defending, mentioning that the practice was just fine for Rembrandt. Nowadays, he has 25 assistants, some of whom he has never met, scattered around the world, producing his work.

Some paintings contain 100% of his brushwork, some contain none, and the rest are a variable hybrid — but all of them are his ideas.

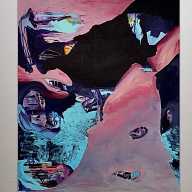

“In the 80s, my work would comment on relationships”, he explains. “I was commenting on humanity. My work dealt with alienation, loneliness, technology, corporate greed. Now, I still explore those themes, but I’ve added more, like commentary on art history, romance, and illogical surrealism. I feel that I’ve become more complex in the grand scheme of things, and my work has become more positive.”

Kostabi had another creative outlet, but he put it aside when he moved to New York. He had taken piano lessons from his mom, a piano teacher, and had some minimal music theory classes in college, but he was basically a self-taught composer.

“I stopped doing music until I made money,” he states. “I felt that I had a head start doing art.”

Once he jumped back into music, he began composing and collaborating with a variety of musicians who helped to flesh out his ideas, including the noted avant-garde legend Ornette Coleman and composer Gene Pritsker, who has been the director of the Composer’s Concordance for the last 20 years.

Pritsker, who has produced concerts in Kostabi’s spaces since the 90s, admits that Kostabi’s compositions are “simple, not pretentious — he has a melodic style and he knows how to surround himself with the right people.” He adds that “there’s a connection between his art and his music. His art is more refined, but his music has unique melodic ideas.”

Recently, on Halloween, the Chelsea headquarters of Kostabi World featured a chamber music concert that was presented as a battle of the composers, pitting the compositions of Pritsker against those of Charles Coleman, but also featuring the same piece by Kostabi, “Springfield Cat,” in different arrangements created by the two.

It was as friendly a competition as it gets, considering that the two contestants were decked out as the devil (Pritsker) and a priest (Coleman). The audience chose the winner, bestowing their blessings on the priest.

Kostabi is as involved now with his music as his art, playing his Steinway almost every day.

“My music is almost always melodic, with influences from Satie to Stravinsky to Ornette Coleman, who I consider a mentor,” he says. “I try to write memorable melodies. … My goal is to have my music replayed.”

Kostabi has done well, but he’s also given back. He regularly contributes to charities, citing those that benefit AIDS and animals as the top two, followed by the Parks Department, children’s hospitals in Italy (where he has another studio), education and many others.

The multi-faceted artist has seen his work seep into pop culture in the form of album covers — “Use Your Illusion” by Guns and Roses and “Adios Amigos” by The Ramones are two examples — and his work is in the permanent collections of over 50 museums, including MOMA, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Guggenheim, the Brooklyn Museum, the National Gallery in Washington D.C., the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles and the National Gallery of Modern Art in Rome.

“I’ve created 29,000 paintings, and all of them have sold, so somebody likes them!” he notes before musing on their meaning. “I want people to enter the art and read their own story. … I want them to continue to be open to interpretation. I want my art to be remembered for the multitude of thoughts that they generate.”

Kostabi’s work is regularly on view at the Park West Gallery in Soho (parkwestgallery.com). He is part of a group show of Pop Art opening at the Martin Lawrence Gallery (martinlawrence.com) on Nov. 21, alongside Warhol, Haring and others. His website is mkostabi.com.