Mayor Bloomberg outlined ideas Tuesday to prepare the city for future storms including possibly building “Seaport City,” a neighborhood patterned after Battery Park City.

BY TERESE LOEB KREUZER with JOSH ROGERS | In a building at the Brooklyn Navy Yard where battleships were once built, on June 11, Mayor Michael Bloomberg outlined plans for another battle that the city will be fighting for decades to come — the battle to address the risks presented by climate change. These include not only hurricanes and storm surges, but sea level rise, heat waves, droughts and heavy downpours.

“As bad as Sandy was, future storms could be even worse,” Bloomberg said. “In fact, because of rising temperatures and sea levels, even a storm that’s not as large as Sandy could — down the road — be even more destructive.”

New York City has 520 miles of coastline. The New York City Panel on Climate Change, comprised of climatologists from leading universities in New York and New Jersey, predicted in a report released on June 10 that sea levels in New York City could rise by more than two-and-a-half feet by mid-century. This would mean that up to one-quarter of the city’s land area, where 800,000 people live today, would be in the floodplain.

“If we do nothing, more than 40 miles of our waterfront could see flooding on a regular basis, just during normal high tides,” Bloomberg said.

Sandy cost the city $19 billion in damages and lost economic activity. According to forecasts, by mid-century, a storm like Sandy would cost the city $90 billion.

“This leaves us with a few clear choices,” said Bloomberg. “We can do nothing and expose ourselves to an increasing frequency of Sandy-like storms that do more and more damage, or we can abandon the waterfront. Or, we can make the investments necessary to build a stronger, more resilient New York — investments that will pay for themselves many times over in the years to come.”

Bloomberg has said repeatedly that the city cannot — and will not — abandon the waterfront.

Rendering of temporary barriers that could be erected near East River Park.

In a 440-page report called “A Stronger, More Resilient New York” released on June 11, the city identified 15 critical areas that must be addressed to protect New Yorkers against climate change. These include coastal defenses, buildings, utilities, food and fuel supply, healthcare, transportation and telecommunications.

In addition, the report looked at five sections of the city that suffered the most damage from Superstorm Sandy and proposed measures to protect them. These communities include the Brooklyn-Queens waterfront, the east and south shores of Staten Island, South Queens, Southern Brooklyn and Southern Manhattan, the area south of 42nd St.

Bloomberg said that some of the protective work has already begun while other parts of it will require further study and significant financing.

The report also calls for installing in the first phase “adaptable floodwalls” to protect the Financial District, Chinatown, the Lower East Side as well as other parts of the city. This would be a mix of temporary and permanent structures, which “can also be integrated with the urban environment to provide access to the waterfront for recreational, transportation and commercial uses.”

Catherine McVay Hughes, Community Board 1’s chairperson, said she was pleased to see that the recommendations included short-term solutions for Lower Manhattan as well as so many detailed measures to protect critical infrastructure such as utilities.

Bloomberg said that beaches are being restored in Staten Island and that protective barriers are being built. At Breezy Point and in the Rockaways, dunes have been proposed. The restoration of natural wetlands will lessen waves on the South Shore of Staten Island and throughout Jamaica Bay.

Massive storm surge barriers have been suggested by some marine scientists to protect New York City. Bloomberg said, “Even though a giant barrier across our entire harbor is not practical or affordable, smaller surge barriers are feasible, and they could have prevented a lot of the flooding we saw during Sandy.”

He said that one such barrier could be at Newtown Creek to protect Greenpoint and Long Island City and another could be at Coney Island Creek. He also proposed a surge barrier at the mouth of Jamaica Bay. He admitted that such a barrier would be “very complicated” and take years to build, requiring “real study so we can determine if it’s worthwhile, but that analysis can begin today.”

The Army Corps of Engineers will be enlisted to do much of this work.

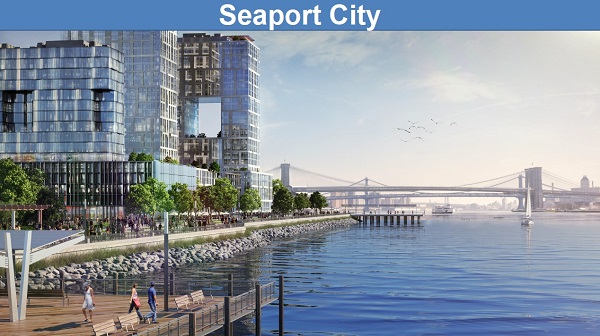

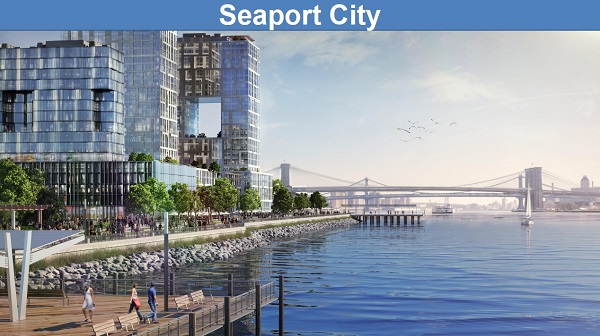

One of the most ambitious of the plans that Bloomberg put forward was for something he called “Seaport City” that could be built along the East River between the Brooklyn Bridge and the Battery Maritime terminal. He described it as a wall of levees, built into the East River, on top of which apartment buildings and office space could be erected, helping to offset the construction costs.

This would be a blue-sky proposition, requiring much study and a realistic financing plan.

“This is a long-term proposal,” Seth Pinsky, president of the New York City Economic Development Corporation and the head of the team that generated the report, told Downtown Express.

“It would require significant input from the community,” he said. “The goal is to create new development opportunities and to do it in a way like with Battery Park City where we can not only pay for it but protect the land behind.”

He said that none of this building would impact the old structures in the Seaport. “It would be built on new land in the East River,” he said. “It would be fully compatible with all the plans that are currently out there for the Seaport.”

Without including what Seaport City might cost, Bloomberg pegged the cost of what the city was proposing at $19.5 billion.

“Approximately $10 billion of that is covered by a combination of city capital funding that’s already been allocated and federal relief and other moneys already designated for the city,” he said. “Another $5 billion should come from the federal government in subsequent rounds of Sandy relief that has been appropriated by Congress, as well as through FEMA risk mitigation funding and other sources.”

He said that “we’ll press the federal government to cover as much of the remaining costs as possible.”

Bloomberg has 203 days remaining in his term as mayor. Clearly, the climate-change protection work will only have just begun by the time he leaves office. But, he said, the work is urgent “and it must begin now. So we will use every one of the next 203 days to get as much work as possible under way and to lock in commitments wherever we can.”