By Lincoln Anderson

The embodiment of DIY, Michael Shenker — a central figure in the East Village squatter and activist scene — could fix up a burned-out tenement building and rewire the whole place for electricity.

Sadly, though, he couldn’t repair his own failing body.

On Saturday morning, he died at Beth Israel Hospital at age 54. As a result of hepatitis C, he had endured liver problems. About six months ago, doctors diagnosed him with liver cancer. The disease progressed quickly. According to friend Frank Morales, a fellow longtime squatter and activist, Shenker was unable — possibly ineligible because of his medical condition — to get a liver transplant.

Activist Rob Jereski was at Shenker’s side, holding his hand, when he died. Shenker’s last words were to say he felt tired and wanted to rest. He died peacefully. Jereski tried to run against Congressmember Carolyn Maloney in the Democratic primary a few years ago but was kept off the ballot after she successfully challenged his petitions. More recently, he had been working as an electrician with Shenker, who was a self-taught, master electrician.

Shenker had been bedridden at his E. Seventh St. home for about a month, but tried to stay out of the hospital as long as he could. Friends cooked for him, and brought DVD’s with film noir and gangster movies for him to watch. The day before he died, however, he was in obvious pain, dehydrated and writhing. At Beth Israel he was rehydrated with an IV and was comfortable for his final 24 hours, according to friends.

Morales said, in a last-ditch effort to save him, friends had tried to get Shenker to do a “liver cleanse” by eating only raw food and seaweed. But Shenker, who was a very good cook, wasn’t having it.

“He loved his sauces,” Morales said. “And he always said, ‘Quality over quantity.’ He wasn’t about to eat seaweed the last month of his life.”

A suburban kid from the Great Neck area of Long Island, Shenker came to live in the East Village in 1970, when he was just 15. His mother, a model, had been the Ipana toothpaste lady in TV commercials, which sometimes featured cameos by Shenker and his brother. But things at home weren’t going well, and Shenker decided he had to get out.

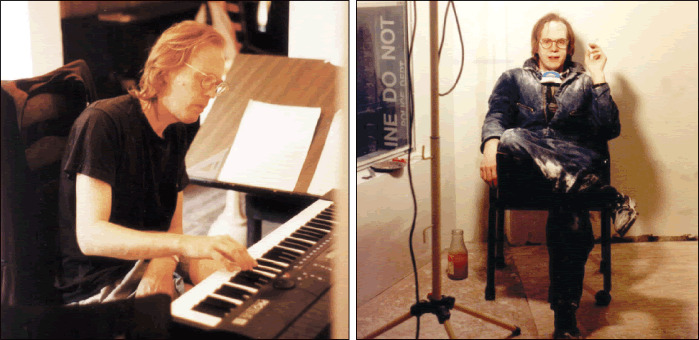

The bohemian East Village, with its flourishing music scene at the Fillmore East, naturally drew Shenker, an aspiring musician. (He would later go on to compose a “Squatter Opera,” excerpts of which were performed at Theater for the New City in the 1990’s; and he also performed internationally as a pianist with the Living Theatre.)

When Shenker first arrived in the East Village, he was homeless and ran with a rough crowd. For a while he lived in a storefront space, but lost it after a fire. Meanwhile, neighborhood rents kept rising, making it increasingly hard to find affordable housing.

In a 2008 interview with The Villager, Shenker recalled how he first learned of squatting. He had been sitting in Life Cafe, at 10th St. and Avenue B, when, he said, “This weird girl Natasha I used to play chess with looked over at me and said, ‘Mike, have you ever heard of squatting?’”

In 1984, Shenker moved into his first squat, 319 E. Eighth St., then, in 1987, switched to 209 E. Seventh St., another building squatters were restoring. A fire had gutted the tenement’s front half, leaving it an empty shell. It was a major rebuilding job. Today the only thing that distinguishes the building from its neighbors is a funky front-door lintel made from bottles that emits a colorful glow at night.

After forcibly evicting many of the East Village squatters in the 1990s, City Hall, in 2002, took a radically new approach: Eleven of the 12 remaining East Village squats were sold for $1 apiece to the nonprofit Urban Homesteading Assistance Board. Under the agreement, the squatters, with UHAB’s guidance, would bring their buildings up to code within one year, then buy them — for just $250 per apartment — and the buildings would become permanently affordable, Housing Development Fund Corporation, or H.D.F.C., co-ops.

Shenker played a key role in the early negotiations that set the stage for the squatters’ historic deal with the city, which made international headlines when the story broke.

Spoke out against cap

Shenker, however, was subsequently one of the leading critics of the process with UHAB, charging that the required renovations took too long and that the squatters — now redubbed “homesteaders” — were being saddled with crushing debt on construction loans. In fact, many of the squatters were unhappy about the process. Shenker, though, was also the loudest voice for the homesteaders being allowed to sell their units for market-rate prices, as opposed to having the sale price capped, which was the original deal with the city.

It was a controversial position for Shenker to take, and not all agreed with him. But he said being allowed to sell his apartment for only around $150,000 was unfair, given the sheer amount of sweat equity — as well as cash — he had put into it. On the market, he said, the apartment in the now-gentrified East Village could fetch $800,000.

“We poured all that concrete, put in the stairs, the landings,” Shenker told The Villager two years ago. “Put in floors, plumbing, electric. … I moved into a building without heat, hot water, no windows, no floors, no roof. I have put over $150,000 of cash into my apartment. There’s no way I could be compensated financially for the work I put into this building — as well as empowering people on issues of housing. Landlords had completely abandoned the neighborhood. We’ve homesteaded — we’ve created equity for ourselves.”

When, nearly 20 years later, he was finally done with all the work on his apartment, it was immaculately furnished, boasting a sunken living room, moldings and expert tiling — which he, of course, did himself — in his kitchen and bathroom.

In his living room, above the mantle, was a backlit, stained-glass window set into the wall. Shenker told The Villager he had bought it on the street for $20. But East Village activist John Penley later said he knew, for a fact, that it was from the old Church of All Nations building, at Houston St. and Second Ave., which was razed for new housing by AvalonBay as part of the Cooper Square Urban Renewal Project. Told of the stained-glass window, Chris Flash, publisher of THE SHADOW, recalled that Shenker had squatted in the Church of All Nations building — which was occupied by a group called CUANDO — for a period.

Left unit to a squatter

Ultimately, though, Shenker didn’t have the energy to keep pushing for market-rate resale prices for the homesteaders in the face of his declining health, which became his overriding concern. Morales said Shenker arranged for his apartment to be left to Deb Lee, “one of the original squatter chicks,” as Morales put it, who is living in the Midwest but remained in touch with Shenker.

Beyond his squatter activism, Shenker fought for affordable housing, in general, and the preservation of the East Village and Lower East Side’s community gardens. He and other activists saved ABC No Rio, at the eleventh hour, persuading the city’s Department of Housing Preservation and Development not to evict the arts collective from its Rivington St. building. He was also passionately against the war in Iraq.

Articulate amid the chaos of demonstrations and rallies, he often led them, giving fiery, impassioned speeches, stridently making the case for why a given garden, squat or community center must be saved. But he didn’t just talk the talk.

“He was not afraid to put his body on the line,” said Morales. “When Bush came to the U.N., gardens, blocking various mayors from doing what they were trying to do to us. … He had fire in his gut.”

Shenker figured he’d been arrested at least 20 times over the years, mainly in protests to save community gardens and squats from development. In one notable bust, Shenker disrupted a 1998 auction of East Village and Lower East Side city-owned properties at One Police Plaza. Shouting, “People of the Lower East Side — stand your ground!” he was dragged out on his knees and shouting by two officers. Later, live crickets were released in the auditorium, causing further pandemonium — but Shenker had set the stage with his statement.

Seen as ‘troublesome’

In 2004, Shenker was surprised to learn that he — along with his friend the late Brad Will — was on a list of “50 leading anarchists” under police surveillance during the run-up to the Republican National Convention. The individuals were described on ABC’s “Nightline” as “troublesome, even dangerous.” Will was deeply offended to be characterized as violent. Shenker just found it a bit humorous and shrugged it off. Shenker later told The Villager he did identify somewhat as an anarchist.

In the mid-1990’s, Will lived in a room of Shenker’s apartment. Going on to become an IndyMedia journalist, Will was shot to death by paramilitaries in Oaxaca, Mexico, while covering a popular uprising there in 2006.

In 2005, Shenker and the artist Fly, his neighbor in the squat, were seriously injured when, while walking home from a movie, they were hit by a turning S.U.V. in a crosswalk at 23rd St. and Second Ave. Shenker was knocked unconscious and had swelling on his brain, and for a while, there was fear he wouldn’t survive. But he pulled through.

Following Shenker’s death, friends and fellow activists remembered him as a committed activist and a truly unique individual who made a difference.

“I remember Mike as multifaceted, kind of a renaissance man in many ways,” said Morales. “The one thing that struck me was his dedication to the downtrodden. He was so committed. Esperanza Garden [which was ultimately bulldozed by developers], people that live in shanties, people in Fallujah. He was just a very committed fighter for human rights. He was tenacious in the fight for justice and peace. It was about not letting something go down uncontested.”

Morales noted Shenker was an accomplished songwriter and performer, favoring R&B and old-style jazz standards. Over the past year, seeking to make up for lost time in his music career, Shenker had been playing piano and performing regularly at 5C Cafe in the East Village. Morales, an ordained Episcopal priest who was once a rock singer himself, teamed up with him for some shows before Shenker’s health declined, performing together as “Mike Champagne” and “Frankie Starlight.”

“His real love was opera,” Morales noted.

Hope to publish work

Morales and Fly both said they’re going to work to try to get some of Shenker’s works published, including some of his early squatter diaries, as well as his musical pieces. Morales said Shenker also wrote a play about John Brown.

Flash, of THE SHADOW, the East Village anarchist newspaper, recalled that Shenker had a bad fall when his squat was under renovation, plummeting down two stories.

“He survived a really bad fall in his squat in the late ’80’s. He had to wear a back brace for the longest while,” Flash said. “He was a master strategist and tactician. If not for him, a lot of people wouldn’t be living in homesteaded buildings right now. He was just a very decent guy. I can count on less than two hands the number of truly reliable and sincere people in the scene who will do what they’d said they were going to do. He’d never let you down.”

Longtime friend and ally Penley had a falling out with Shenker when he argued for market-rate resales of the former squatter apartments. Penley felt it was a betrayal of the principle of squatting as affordable housing, which had allowed the homesteaders to get their apartments in the first place.

“While Michael and I had our differences over the selling of the squats at market rate,” Penley said, “I consider Michael a neighborhood hero and I really loved him to death.”

‘A huge inspiration’

Fly, his neighbor in 209 E. Seventh St. since the early 1990’s, said, “Michael took me in and let me live in his space while I was building my apartment across the hall from him. He was a huge inspiration to me — a true radical and a true friend. He was an accomplished musician, electrician, artist, writer — he really did it all and did it all with a passion.”

She recalled the time when Shenker bolted outside after a Con Ed crew had cemented up a conduit, ripping out the wet cement with his bare hands, so that the squatters would be able to get electricity.

She remembered another time when she was fretting over whether to install a window in a wall that would allow more light into her kitchen, but which ran up against the house’s “politics.” Shenker counseled her to do what made her happy, and to decide whether she wanted to live in the dark or light. She resolved to do it.

“That’s what Michael did,” Fly said. “He helped us to have the strength and courage and community to be able to live in the light.”

On Sun., Oct. 17, Michael Shenker’s ashes will be interred beside his mother in Pinelawn Cemetery on Long Island.

Memorials, celebrations

On Fri., Oct. 8, a memorial for Shenker will be held at 5C Cafe, at 5th St. and Avenue C, starting at 7 p.m. Music by Burt Ekert — Shenker’s piano teacher — and friends will start at 8 p.m.

On Sun., Oct. 10, Time’s Up will hold a garden party at 3:30 p.m. at El Jardin Del Paraiso, at Fourth St. between Avenues C and D, where people will share stories about Shenker, a co-founder of the More Gardens Coalition. (Bring food and music to share.)

On Sat., Oct. 16, there will be a march around the neighborhood in honor of Shenker. People will gather at 5 p.m. in the middle of Tompkins Square Park, and end the march at 7 p.m. at Maryhouse (The Catholic Worker), at 55 E. Third St., where Shenker’s funeral will then be held. (E-mail one or two of your favorite photos of Shenker for a slide show to fly@bway.net .)

On Sun., Oct. 24, from 6 p.m. to 10 p.m., a celebration of Michael Shenker will be held at the 6th St. Community Center, 638 E. Sixth St., from 6 p.m. to 10 p.m., with performances by Eric Drooker, the East River String Band, Seth Tobocman and Fly and the new BX Ballet performing excerpts from Shenker’s “Squatter Opera.”