BY ALEJANDRA O’CONNELL-DOMENECH | The Central Park statue honoring women’s suffragettes Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony will be redesigned to include Sojourner Truth.

The Monumental Women Statue Fund announced the redesign in a statement published on its Web site last week.

“When the Public Design Commission unanimously approved our previous design with Anthony and Stanton — but required that a scroll with the names and quotes of 22 diverse women’s suffrage leaders be removed — we knew we needed to go back to the drawing board and create a new design,” said Pam Elam, president of M.W.S.F., in the statement.

(Courtesy GLENN CASTELLANO/ NEW-YORK HISTORICAL SOCIETY)

The statue originally depicted Stanton and Anthony working alongside each other at a desk over a long scroll that tumbled down to an old-fashioned ballot box below them. In a homage to the movement’s breadth, the scroll featured the names of nearly dozen other women — including Sojourner Truth, Lucy Stone, Ida B. Wells, Anna Howard Shaw, Lucretia Mott, Matilda Joslyn Gage and Alice Paul — who fought for women’s suffrage.

The statue will now show Stanton, Anthony and also Truth working together in Stanton’s home, “as they often did in life,” the M.W.S.F. statement said.

But just like the statue’s original design, the new redesign is facing some criticism.

When the nonprofit announced last year that it would be creating the first statue in Central Park honoring real women, the decision to create a monument featuring two white women to represent the broad and diverse movement was met with immediate criticism.

In January, icon feminist Gloria Steinem took issue with the statue and told The New York Times that Anthony and Stanton looked as if they were standing on the names of the other women, therefore diminishing their efforts. In March, both the New York Times and The Washington Post published pieces that called the statue a “whitewashing” of history. Both pieces referenced Stanton biographer Lori D. Ginzberg’s description of the suffragist as someone openly used racist language, referring to black men as “sambos” and rapists, and who prioritized the rights of white, middle-class, educated, Protestant women over others.

Last month, Harlem historian Jacob Morris declared the statue racist and drafted a community board resolution calling for a halt to public funding for the monument barring a redesign. Harlem’s Community Board 11 has expressed support for the resolution, but is currently on recess for August and will vote on it next month.

Although Morris told this paper that the redesign was a step in the right direction, he said it is still not enough.

Morris and Todd Fine, a Ph.D. student at the City University of New York Graduate Center, drafted a letter to Elam and Coline Jenkins of the Statue Fund, asking that those in charge of the redesign not make the decision lightly, in order not to repeat the same mistake. Other signers include Leslie Podel, the creator of “The Sojourner Truth Project,” as well as university professors from Yale, Columbia, N.Y.U., Lehman College, Brown, Duke, and Fordham.

“If Sojourner Truth is added in a manner that simply shows her working together with Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Staton in Stanton’s home, it could further obscure the substantial differences between white and black suffrage activists, and would be misleading,” the letter states.

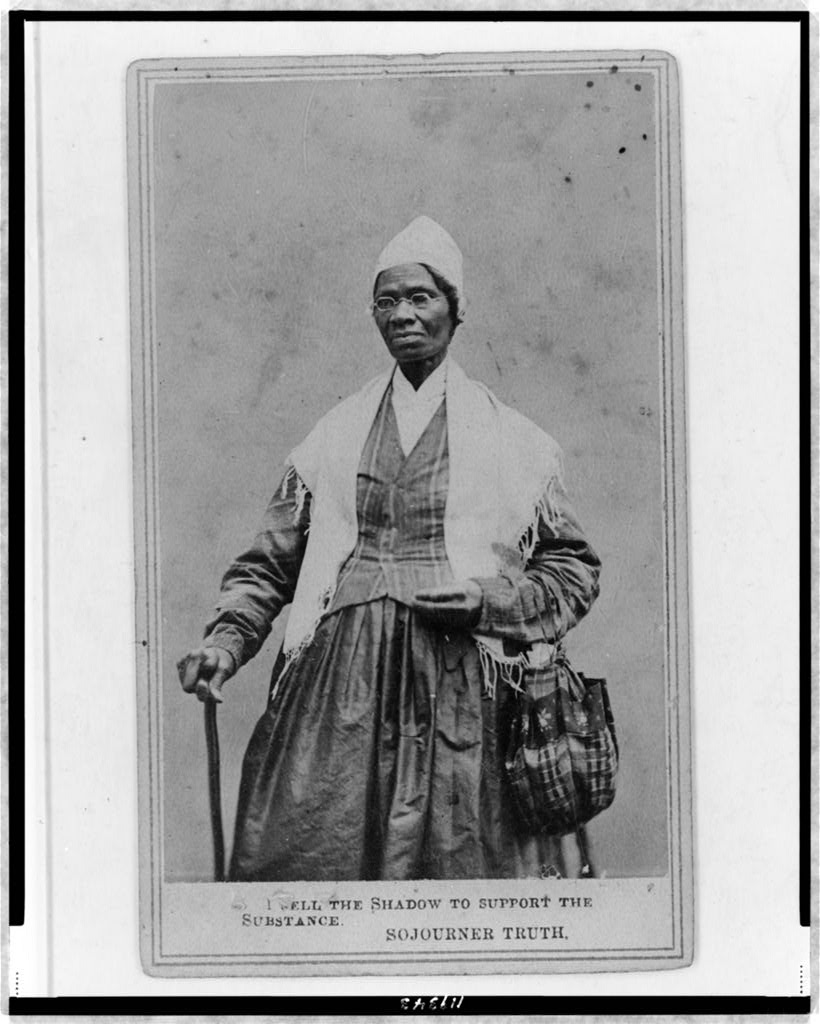

Truth was born into slavery in Ulster County, in Upstate New York, in 1797, escaped from slavery in 1827, and later joined the abolitionist movement. By the 1850s, Truth had joined the fight for women’s rights. At the 1851 Women’s Rights Convention in Akron, Ohio, she delivered what is now recognized as one of the most famous abolitionist and women’s rights speeches in American history, “Ain’t I a Woman?”

Although there is documentation to prove that Truth stayed at Stanton’s home, Morris and Fine argue that there is no evidence to prove that they planned to work as a group of three. Also, grouping the three women together doesn’t adequately reflect their sharp disagreement over who should get the right to vote. Cady and Stanton prioritized white women getting enfranchised first, but Truth wanted universal suffrage.

In order to create an accurate and inclusive monument, Morris and Fine are asking the Monumental Women Statue Fund to change the piece’s “thematic scope” and consider black figures whose efforts were marginalized during the fight for women’s suffrage.

“We believe that there may be elegant ways to memorialize the full scope of the suffrage movement to incorporate these challenging differences,” their letter states, “but they will require careful consideration, explicitly including black community voices and scholars of this history.”

If the city’s Public Design Commission approves the redesign, the monument is slated to be erected on Aug. 26 of next year on Central Park’s Literary Walk.