Lower East Sider Nina Howes was unsurprised when her crosstown trip on the M21 bus to the Hudson River waterfront was cut short by gridlock traffic going into the Holland Tunnel during the evening rush hour on Monday, Sept. 27.

“It takes 10 years to get down to the river,” said Howes as the bus came to a crawl on W. Houston Street near Varick Street. “We’re not going to go the whole way because there’s too much traffic.”

The bus line has had to suspend service at its western end on almost two-thirds of all weekdays in the last six months, an amNewYork Metro analysis has found, as a seemingly-endless stream of traffic goes from Manhattan to New Jersey every evening rush hour.

When vehicles heading to the Garden State start to clog up the blocks near the downtown tunnel entrance, the Metropolitan Transportation Authority’s New York City Transit usually suspends service to four stops — two in each direction — on a loop around that area.

To the chagrin of riders and Twitter transit watchers, the agency like clockwork sends out notices of the reduced service on social media, showing a map of the cancelled stops and a message that is usually a variation of the same message:

M21 bus service is suspended west of Varick St because of heavy traffic entering the Holland Tunnel. Buses will end/begin at Sixth Ave/Spring St. pic.twitter.com/zLz0rPXHpK

— NYCT Bus (@NYCTBus) September 24, 2021

An amNewYork Metro review of the agency’s Twitter posts showed that NYCT suspended service on that section due to tunnel-bound traffic a whopping 87 out of 132 weekdays since March 28, or 65.9% of the time.

It was worst in June when MTA called off the last stops on all but one weekday evening, or 21 times.

Public transportation boosters say the regular blockage shows why the state should move ahead with charging drivers to enter downtown Manhattan under the MTA’s proposed congestion pricing program, in order to encourage more people to switch to public transit and free up the roads.

“Few things are a better argument for congestion pricing,” said Danny Pearlstein of the advocacy group Riders Alliance.

MTA estimates the scheme will cut traffic by 15-20%, but doesn’t expect to implement it until 2023 after completing a 16-month environmental review required by the federal government.

Transit officials are in the process of holding public hearings about congestion pricing until Oct. 13, seeking feedback from New Yorkers and commuters from across the tri-state area.

‘Always been a mess’

The streets around the Holland Tunnel entrance have long been a bottleneck, and recent counts by the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, which operates the Holland Tunnel, shows that traffic is has recovered to almost pre-pandemic levels, with 1,234,735 in July 2021, about 93% of the 1,330,571 vehicles crossing the tunnel in July of 2019.

Meanwhile, MTA’s buses have come back to about 61% daily ridership compared to 2019 and the subways reached more than 55%, according to the transportation authority’s most recent counts.

Port Authority spokesperson Scott Ladd said congestion has gotten worse not only due to rebounding vehicle traffic, but also because of construction on nearby streets, such as Spring Street and Canal Street, that have cut the number of lanes for cars and buses.

He referred further comment to MTA and the city, adding that the M21 bus route is not on or even that close to Port Authority property.

An MTA spokesman said in a statement that the issue predates the COVID-19 pandemic and that the agency chooses to temporarily eliminate the four stops to prevent delays on the remaining route.

“Due to traffic conditions at the Holland Tunnel, the M21 route was experiencing severe delays. As a result, beginning before the COVID pandemic, MTA NYC Transit elected during certain rush hour periods, when traffic backs up at the Holland Tunnel, to temporarily suspend two of the route’s 20 stops in each direction that are west of the tunnel, thereby alleviating the delays,” said Aaron Donovan.

Lisa Daglian, executive director of the Permanent Citizens Advisory Committee to the MTA, the agency’s rider’s advocacy group, said MTA and the city’s Department of Transportation — which is responsible for the streets — should join forces and implement measures like giving buses signal priority on traffic lights and adding enforcement cameras.

“That area has always been a mess for traffic,” she said. “What kind of solutions can be put into place so that buses can move.”

DOT did not respond to a request for comment.

MTA officials noted the cut only removes about 10% of the bus’s 41 total stops between the Lower East Side and SoHo, but Daglian said that forcing straphangers to walk even a handful of extra blocks can be challenging — especially in an area where bumper-to-bumper traffic routinely blocks the crosswalks.

“Those last four stops can mean the difference between somebody with a disability being able to get home and not being able to get home,” she said. “Somebody who has to then fight their way through those cars and other vehicles to get where they need to go — transit is supposed to make your life easier and not get stuck in traffic.”

‘A very bad precedent’

Pearlstein lambasted government transit officials for giving in to congestion.

“I don’t think that we should cede territory from bus riders to drivers. It sets a very bad precedent,” he said.

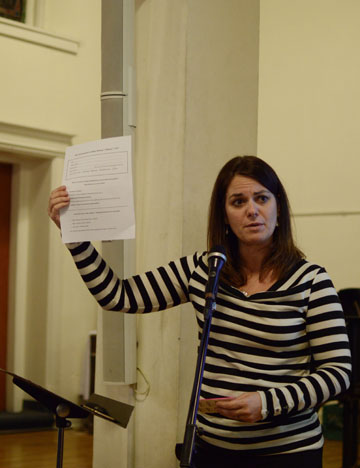

On Monday evening, Howes’s M21 bus slowed down to a snail’s pace as it approached Varick Street and she got off after the bus driver informed her that the route would once again be cut short because of traffic.

Howes, who uses a cane, decided to walk the remaining four blocks to the waterfront.

“You have to get off at Sixth or Seventh Avenue and walk the rest of the way,” Howes said. “I’m glad I’m walking better, but if my feet were as bad as they were, I’d be mad.”