BY JOSEFA VELAZQUEZ, THE CITY | This story was first published on Sept. 30 by The City. A key task of the state housing agency just got a lot tougher with a new rent law that expands tenants’ rights and the time they have to file complaints alleging their landlords overcharged them.

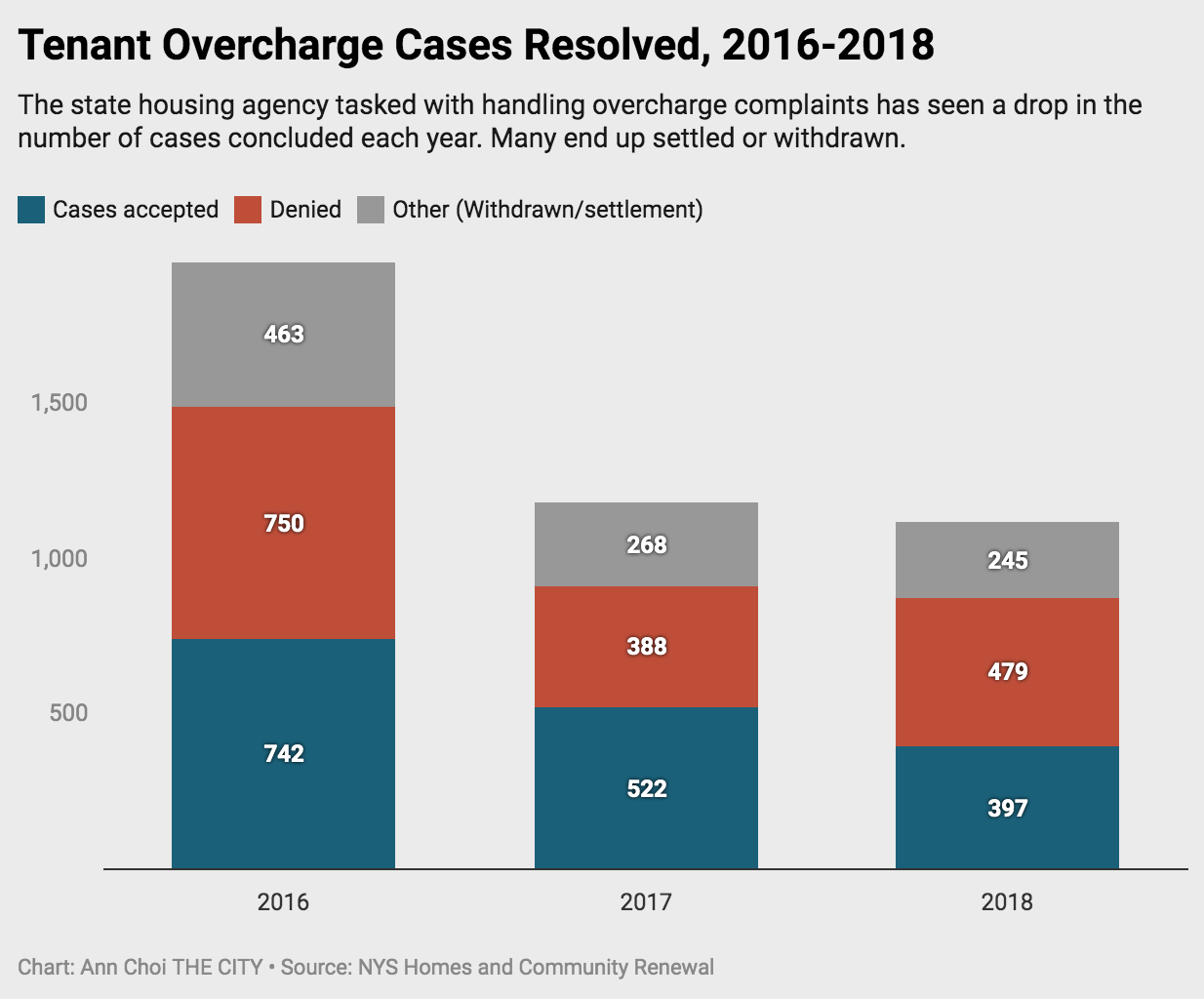

Yet the Division of Housing and Community Renewal was already drowning in more cases than it could quickly handle, numbers obtained by THE CITY show.

State stats indicate it takes DHCR’s Office of Rent Administration an average of 24 months just to get overcharge cases on rent-regulated apartments assigned to an examiner.

After that, it can take another six to nine months to process the case, leaving some tenants waiting for up to three years waiting for a response — by which point many have given up the fight.

’The Person I Spoke to Laughed’

It’s been roughly 15 months since Rebecca — who did not want her full name used for fear of retribution by her landlord — filed an overcharge complaint with DHCR.

“The person I spoke to laughed when I asked about the status of my case” nine months after filing, she recounted. “They said it would take at least a year to assign the case unless I could prove I had eviction proceedings. It’s ridiculous to have absolutely no progress after nine months.”

When she’d signed the lease on her Crown Heights apartment in early 2017, there was no mention the apartment was rent stabilized.

It was “happenstance” that Rebecca discovered her apartment was covered by rent regulations, she told THE CITY.

She asked to see the rent history on the unit from DHCR and discovered the previous tenant’s rent was $545 in 2016 — a fraction of her $2,227 monthly payment.

The landlord hadn’t provided evidence, which they’re required to do at a renter’s request, detailing apartment renovations that had been made in between tenants to merit the rent spike.

Over the next year Rebecca grappled with the right approach: go to Housing Court, where tenants may also file overcharge cases, or complain to DHCR. She chose the latter.

In July 2018, she filed an overcharge complaint. The case could lead to her getting back money she overpaid, as well as a rollback of her monthly rent to the correct regulated level.

Checking the Receipts

Prior to this June’s historic rent law overhaul by the state legislature, landlords had an arsenal of tools available to increase rent on an apartment.

Particularly vulnerable to abuse was the power to pass on the cost of apartment renovations to tenants — and to use such rent hikes to permanently remove apartments from the domain of rent regulation.

A pending lawsuit from state Attorney General Letitia James alleges one landlord forged documents in order to claim the hikes.

The new Housing Stability and Tenant Protection Act caps the pass-along to tenants at $15,000, and allows such increases only once every 15 years.

Yet DHCR only reviews landlords’ receipts if a tenant files an overcharge complaint, according to the agency — grievances that will come in to an already bottle-necked Office of Rent Enforcement.

DHCR currently has 25 rent examiners in its Overcharge Unit, said spokesperson Brian Butry. Between April and September, the agency received 559 overcharge complaints.

Less than four years after moving into her apartment, a Harlem resident — who did not want to be identified because she’s currently appealing an overcharge decision — filed a complaint with DHCR in fall 2016.

She contended the landlord inflated the costs of apartment renovations by tens of thousands of dollars to increase the rent on the unit by roughly $900 before she moved in.

Meanwhile, leaks in the bathroom and kitchen persisted and “things in the apartment started falling apart,” she said.

In the years since she first filed the complaint, her landlords hired lawyers who have pressed her to settle the overcharge complaint and have pushed for more time.

“It’s not an even playing field, because landlords have attorneys who have more tools at their disposal and can drag things out/try to get you to settle for less than you deserve,” she said in an email.

Nearly three years after she filed her complaint, DHCR issued an order last month denying the tenant had been overcharged.

‘Enforcement Roulette’

At a hearing in Albany earlier this year, several state lawmakers told DHCR Commissioner RuthAnne Visnauskas that some of their constituents had waited between four and seven years to get overcharge complaints dealt with.

“Cases are often complex and each side has time to go back and forth and respond to the different charges,” Visnauskas said, while noting that agency’s new budget included funding for 94 additional staff for the Office of Rent Administration and Tenant Protection Unit.

Andrea Shapiro, program manager and member organizer at the Metropolitan Council on Housing, a nonprofit tenant advocacy organization, wasn’t “terribly surprised” by tenants’ waits of three years or more.

In general, a rental overcharge case takes between one and two years to be resolved, and that’s typically with an advocate helping out a renter, Shapiro said.

Between April and September, 40% of closed cases were either withdrawn or settled.

Aaron Carr, who founded the tenant watchdog Housing Rights Initiative, described the overcharge process as “arbitrary and unpredictable.”

“You can have two overcharge cases that are identical. One resolves in a matter of a few months and the other goes on for 10 years. It’s like enforcement roulette,” Carr said.

“An overcharge case is not rocket science, it’s basic math. Can the landlord justify the rent it’s charging? Did they apply the correct formulas and register the correct rents? DHCR has been around for decades, and, yet, they still act like it’s their first day on the job,” he added.

The long lag time for overcharge cases to be adjudicated has led some tenants to abandon their apartments, Shapiro said.

“Oftentimes they’re doing an overcharge case because they can’t afford the rent,” she said. “And they can’t wait in an apartment they can’t afford.”

Once tenants move out of their units, their overcharge applications are withdrawn from DHCR and the renters are not entitled to compensation, no matter how much they may have overpaid in the past.

Paper Records

DHCR’s slow response times to overcharge complaints — which an agency spokesperson says it’s constantly trying to improve — is tied to both a lack of funding and political will, observers say.

State Sen. Liz Krueger (D-Manhattan) says series of forces have led the agency into the quagmire, including: landlords who either fail to file documentation or submit false documents; glacial technological updates that still leave the agency dealing with paper records; and a chronic shortage of staff.

“In 2019 — I don’t think I’m exaggerating — it’s the only government agency in the state of New York that doesn’t have a functioning computer system,” Krueger said. “Every time a tenant needed anything, you’d be going in search of an actual physical paper trail.”

The new rent laws passed by the state Legislature spell out a host of new responsibilities for the already overwhelmed agency, including increased oversight and auditing. The law also requires annual reporting on trends in the rent stabilization system, a role already played in New York City by the local Rent Guidelines Board.

In recognition of DHCR’s need for additional resources, the new rent law doubled the annual fee landlords have to pay on each of their rent-regulated units to $20.

City Council Piles On

In addition to the Legislature’s directives, a recent City Council law requires owners to provide tenants in rent stabilized units four years of their rental history — a move that could cause even more tenants to file overcharge complaints.

But landlords have to rely on DHCR to produce those records — and it’s “unlikely” that the agency is ready to deliver them on demand for New York City’s nearly 1 million rent stabilized apartments by the time Local Law 113 goes into effect Oct. 8, an agency spokesperson said.

In response to landlord inquiries, DHCR is emailing back an automated response indicating it will not fulfill individual requests for records but instead “will be developing an online automated solution to address this issue.”

Meanwhile, landlords are scrambling to figure out how to comply, said Jay Martin, executive director of the Community Housing Improvement Program, which represents building owners.

“The New York City Council apparently thinks it is important to flood DHCR with requests for documents that tenants can easily receive when needed,” Martin said. “DHCR is now swamped with requests by panicked owners trying to comply with the law, forcing the agency to focus on government redundancy instead of helping owners better manage their property, or helping tenants receive the protections they deserve.”

Krueger put it her assessment of the agency in blunt terms: “I don’t think DHCR is up to the job now.”

“I do believe that we have underfunded DHCR for a very long time. It’s absurd beyond belief that they are the state agency most behind on computerization. Some people will tell you it’s a giant plot. I tend to believe more in incompetence in government than giant plots,” she continued, adding:

“I tend to believe you have to be good at your job to plot.”

This story was originally published by THE CITY, an independent, nonprofit news organization dedicated to hard-hitting reporting that serves the people of New York.