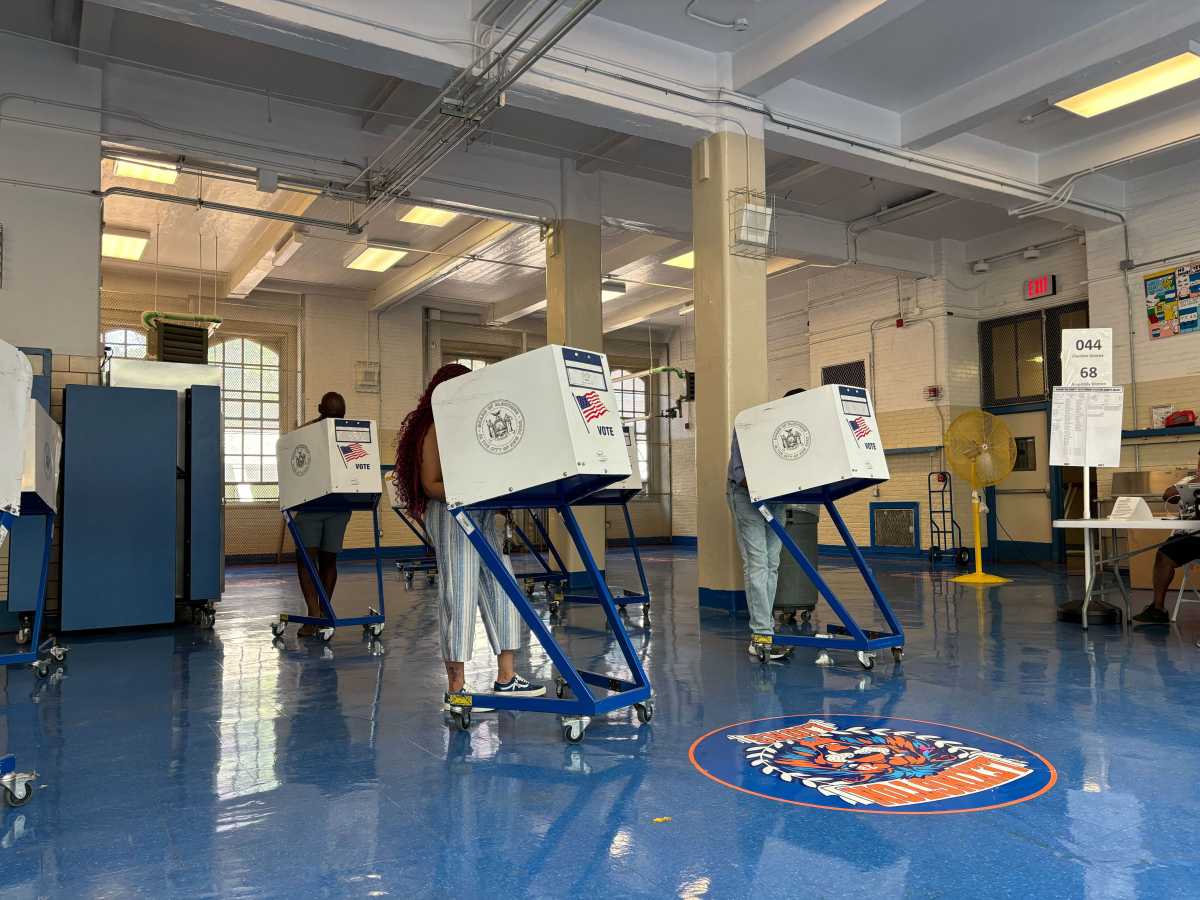

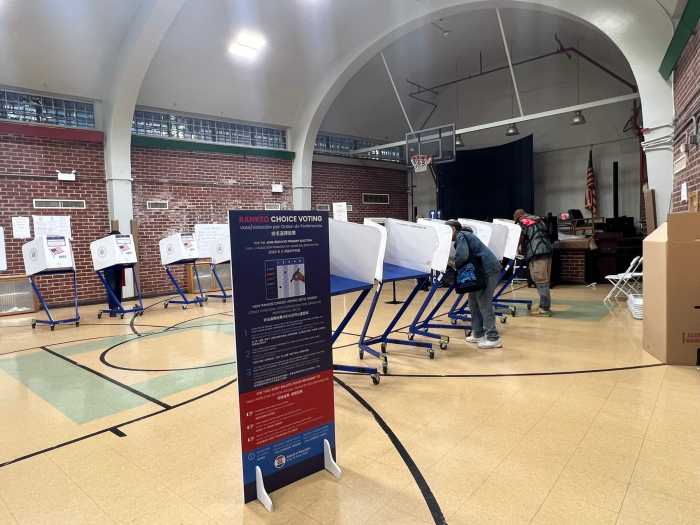

This election year, in addition to the top-tier races for president and US Senate, New York City voters have the chance to decide on six ballot referendum questions.

Early voting in the 2024 general election started on Saturday and runs through this Sunday.

The six questions include a statewide amendment that would enshrine the rights of several vulnerable groups into the state Constitution and five city-level amendments to the City Charter advanced by Mayor Eric Adams’ Charter Revision Commission earlier this year. All six questions will appear on the flip side of voters’ ballots.

However, many of the proposals have drawn backlash on both ends of the political spectrum and have sparked campaigns aimed at convincing voters to reject them. For instance, many City Council members and advocates are urging New Yorkers to vote against the five proposals advanced by the mayor’s commission.

Below is a rundown of each ballot referendum question and the conversation surrounding it.

Proposition 1: Equal Rights Amendment

The first ballot question — known as Proposition 1 or the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) — is a statewide referendum designed to codify abortion rights into the state Constitution.

The ERA was first introduced in June 2022, shortly after the US Supreme Court’s historic ruling overturning Roe vs. Wade, which ended the national right to an abortion and threw decisions about laws governing the practice back to individual states. As is required for all proposed amendments to the state Constitution, the ERA passed the state legislature twice: once shortly after it was first introduced in an extraordinary special session of the state legislature and again in January 2023.

In addition to codifying New Yorkers’ abortion rights, the ERA would also bar state government discrimination against categories of other vulnerable groups. It would outlaw unequal treatment based upon several other categories, including an individual’s ethnicity, national origin, age, sexual orientation, gender, and pregnancy status.

“A ‘Yes’ vote puts these protections against discrimination in the New York State Constitution,” text of the ballot question reads. “A ‘No’ vote leaves these protections out of the State Constitution.”

The state constitution already protects against discrimination based on race and religion.

Although New York already has some of the strongest abortion protections in the country, proponents of the ERA argue enshrining the right to an abortion within the state constitution will protect against possible efforts by future governors or state legisaltures to restrict it.

For much of the past year, a pro-ERA campaign known as New Yorkers for Equal Rights has been working to educate voters about the measure and sway them to approve it.

But, at the same time, there is also a concerted effort led by state Republicans to defeat the proposal. They are trying to dissuade voters from supporting the amendment by claiming it would have multiple unintended consequences, such as paving the way for undocumented immigrants to vote — a notion the measure’s supporters say is false.

One of the ERA’s biggest detractors is a group dubbed the Coalition to Protect Kids.

Similar to state Republicans, the group has focused its messaging not on abortion but instead on the measure’s potential impact on transgender youth. They claim that by eliminating unequal treatment based on age, the proposal would give children access to gender-affirming hormones and surgeries for which they would currently need parental consent.

However, the New York City Bar Association says that claim is false and the measure would not impact parents’ rights to be involved in decision-making around their children’s health care.

Republicans successfully got a state Supreme Court judge to remove the ERA from the ballot earlier this year, only for it to be reinstated by a state appeals court in June.

Proposition 2: Sanitation in NYC

The other five ballot measures are all New York City-specific proposals that would amend the City Charter. Mayor Adams’ controversial charter commission approved them over the summer despite the protestations of many City Council members.

The first of the five proposals — Proposition 2 — would expand the Sanitation Department’s authority to clean city-owned property, including parks and highway medians. It would also give the department enforcement power over street vendors doing business in parks or on highway medians, as well as codify its authority to require city residents and businesses to place their trash in lidded containers — in accordance with the mayor’s plan to containerize refuse across the five boroughs.

“Voting ‘Yes’ will expand and clarify the Department of Sanitation’s power to clean streets and other city property and require disposal of waste in containers,” text of the ballot question reads. “Voting ‘No’ leaves laws unchanged.”

The Sanitation Department argues that the expanded authority would help it be more effective in keeping city streets clean, while opponents have charged that it would give the agency too much power.

Specifically, advocates charge the ballot question is misleading because it does not mention the added enforcement authority it would afford the department against unlicensed street vendors, whom the city has already been aggressively cracking down on — according to a report by Gothamist.

Proposition 3: Estimating costs of Council bills

Proposition 3 is one of the most controversial measures advanced by the mayor’s charter commission because it would potentially give City Hall a far larger hand in the City Council’s lawmaking process.

The proposal would mandate that the council produce a cost estimate for a bill twice, instead of once, before voting on it and make one of the estimates public before holding a bearing on the legislation. It would also allow the mayor’s budget office to produce its own cost assessments for legislation at both points of the process.

Furthermore, the measure would postpone the deadlines by which the mayors must present their budget proposals during their first year in office.

“Voting ‘Yes’ would amend the City Charter to require additional fiscal analysis prior to hearings and votes on local laws, and update budget deadlines,” the ballot question reads. “Voting ‘No’ leaves laws unchanged.”

The charter commission argued the proposal was necessary to bring more transparency around the price tags of certain council bills prior to them being voted on.

But the measure, along with Proposition 4, has drawn the ire of the City Council. They argue it’s nothing more than a power grab intended to diminish the council’s lawmaking authority.

“It is a dangerous attempt to shift power away from the people represented by the City Council to one single individual,” City Council Speaker Adrienne Adams siad in July. “Do you want a king?”

Proposition 4: Public notice on bills affecting city agencies

The fourth ballot proposal, which has also sparked backlash from the City Council, would require the body to provide 30 days public notice prior to voting on legislation affecting the city’s public safety agencies. Those include the NYPD, Fire Department and Department of Correction.

It would also give the mayor and the affected agency the power to hold their own public hearings on the bills.

“Voting ‘Yes’ will require additional notice and time before the council votes on laws respecting public safety operations of the Police, Correction, or Fire Departments,” the ballot question reads. “Voting ‘No’ leaves laws unchanged.”

The commission said the proposal is designed to make the lawmaking process around public safety legislation more open to the public after a controversial bill requiring the police to report on low-level pedestrian stops passed earlier this year.

However, council members charge that, similar to Proposition 3, the measure would shift power from the legislature to the executive and dilute the body’s power to pass public safety legislation that the mayor does not agree with.

Proposition 5: Capital planning disclosure

Proposition 5, among the least contentious proposals, aims to increase transparency around the city’s capital planning process for city facilities.

The measure would require the city to produce more detailed versions of several of its annual and semi-annual reports on its infrastructure needs, including what must be built and fixed.

The proposal would require that one of those annual reports, the “Citywide Statement of Needs,” which details the state of repair for city facilities, include more details about facility conditions and the estimated life for those structures. Additionally, it would mandate that the statement of needs be considered in another semi-annual infrastructure report called the “Ten-Year Capital Strategy.”

“Voting ‘Yes’ would require more detail when assessing maintenance needs of city facilities, mandate that facility needs inform capital planning, and update capital planning deadlines,” the ballot question reads. “Voting ‘No’ leaves laws unchanged.”

The charter commissioner said the proposal was based on testimony from city Comptroller Brad Lander on ways to improve the capital planning process.

However, in a statement earlier this year, Lander said the proposal does not actually consider his recommendations and is “meaningless, does not advance transparency, and fails to improve the city’s capital planning process in any way.”

Proposition 6: Diversity officer, filming permits, archives

Proposition 6, which also has drawn comparatively little backlash, would make an assortment of unrelated changes.

First, it would formalize the role of the Chief Business Diversity Officer, who oversees City Hall’s Minority and Women-Owned Businesses program, in the City Charter. Second, it would give the mayor authority to allow employees of the Mayor’s Office of Media and Entertainment to issue filming permits.

Lastly, it would consolidate two separate boards that handle city archives.

“Voting ‘Yes’ would establish the CBDO to support MWBEs, authorize the mayor to designate the office that issues film permits, and combine two boards,” the ballot proposal reads. “Voting ‘No’ leaves laws unchanged.”