BY STEPHANIE BUHMANN | “Everywhere I looked, everything I saw became something to be made, and it had to be made exactly as it was, with nothing added. It was a new freedom; there was no longer the need to compose.”

When the revered American abstract artist Ellsworth Kelly died on Dec. 27, 2015 at the age of 92, there was a strong outpouring of sympathy in the international art community. In addition to the many leading newspapers, art magazines and blogs who quickly published long obituaries or tributes, social media was rich in passionate proclamations by artists, citing Kelly’s crucial impact. For decades, he had not only been one of the most influential artists of the post-War era, but also one whose quality of innovation was sustained and repeatedly asserted in his more than six-decades-spanning career.

Though best known for his abstract, hard-edged compositions, which often saw him linked to the Minimalist movement of the 1960s, Kelly preserved an independent voice throughout his career. In fact, one of his most widely admired bodies of work allows for overt references, featuring exquisite outline drawings of leaves and plant fragments. His artistic heritage was steeped in the European avant-garde. Matisse, early Kandinsky, and Léger impacted his sense and obvious joy of color — while two of his favorite artists, Brancusi and Mondrian, sparked his interest in reducing shapes to their simplest forms. In fact, all of Kelly’s works were derived from careful observations of the world around him. Chance compositions created by nature or architecture through the interplay of light and shadow were always at the root of his vocabulary, no matter how seemingly abstract. In that sense, the core of Kelly’s work is distillation, stripping the observed subjects to bones made of pure color and form.

When asking several New York-based contemporary artists about what they particularly admired in Kelly, I quickly received various detailed responses. “When I came to New York in 1982, I was an innocent plein-air landscape painter from California,” the abstract artist Leslie Wayne remembered. “I was determined to leave that all behind and explore a brave new world of abstraction. One day I was at MoMA and saw Kelly’s ‘Study for Rebound’ (1955) and it was like a ‘eureka’ moment. I immediately went back to the studio and made a series of paintings based on those two biomorphic shapes. Kelly’s work gave me a way to enter a language I hadn’t yet made my own, and because of that, he has always held an important place in my heart for his early gift of influence.”

Jennifer Riley, who has titled several of her works “According to EK” as an homage to Kelly’s “Spectrum Colors Arranged by Chance” paintings, stated: “I was initially attracted to Kelly’s brilliant colors and bold sophisticated forms. I found myself, later on, seeing, making, and representing my own reality in a subjective, abstracted way. I have Ellsworth Kelly to thank. I think he gave many of us permission.”

Remembering a specific exhibition of Kelly’s plant drawings at the Metropolitan Museum in 2012, artist Kim Uchiyama added: “I [had] two experiences with this work. First, I was really taken by their strength of line and overall design while remaining absolutely delicate and conveying a sense of fluid, organic abstraction. Second, many of the drawings were done in black and white, yet the form clearly came out of feeling, color, weight, and shape. Both of these experiences still resonate with me and give me a lot to think about.”

To Nick Lamia, it is “the incredible richness Kelly was able to conjure using such efficient means” that stands out. “He was like a chef who could create entire feasts with just two or three ingredients. Whether it was large abstract paintings, contour drawings of plants or sculpture, he consistently created engaging and inspiring imagery using just a few elements.”

Kelly’s presence in New York is especially strong due to his long history with both the city and state. Born in Newburgh, New York, he first studied at Pratt Institute, Brooklyn (1941-43), before serving in the military (1943-1945) and joining the Allied Forces in France. After pursuing an arts education at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston (1946-1948) and six subsequent years in Paris on the GI Bill, he returned to the United States in 1954 — for good. By the time he settled in New York, first in a studio apartment on Broad St., and finally on Coenties Slip in Lower Manhattan, he had already made acquaintances with Brancusi, Arp, Miró, Cage and Cunningham (in Europe). Now, his neighbors included Robert Indiana, Agnes Martin and James Rosenquist, among others.

His first New York solo show soon followed at the Betty Parsons Gallery in 1956, and three years later he was included in the landmark exhibition “Sixteen Americans” at the Museum of Modern Art. Though Kelly moved out of Manhattan in 1970, three years before his retrospective at MoMA, he remained in New York State. He set up a studio in Chatham and a home in nearby Spencertown, where he lived and worked until his death.

Fortunately, in New York, Kelly’s work can be sought out at any time. It can be found in the permanent collections of all of the city’s leading art museums. In addition, Matthew Marks Gallery, which has exhibited Kelly’s work since the early 1990s, is currently hosting a project that should not be missed.

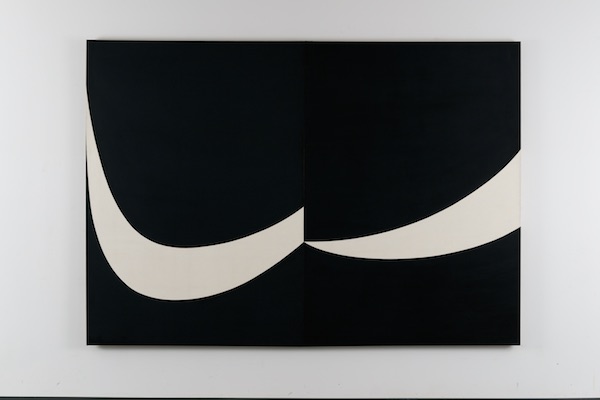

The Whitney Museum of American Art also owns many works by Kelly, including the stunning “Atlantic” (1956). Measuring more than nine feet wide, it is the largest of the artist’s black-and-white canvases of the late 1950s.

It marks the ambitious culmination of many studies and several smaller paintings of the same compositional theme. The latter was inspired by shadows cast across the pages of a book, which Kelly observed while reading on a bus. The diptych structure of “Atlantic” reflects the facing pages of the book. However, as if to turn a spotlight onto the shape that caught his attention, Kelly chose to reverse the light: Now the former shadow appears white, accentuated by the darkness of its surroundings. At 99 Gansevoort St. (btw. 10th Ave. & Washington St.). Visit whitney.org or call 212-570-3600.

The Museum of Modern Art lists no less than 235 works by Kelly online, including many that are not on display, such as the exquisite “Brushstrokes Cut into Forty-Nine Squares and Arranged by Chance” (1951), a work made of cut-and-pasted ink drawings. Currently on display in the atrium, however, is the large-scale “Three Panels: Orange, Dark Gray, Green” (1986). In this triptych, three shaped canvases engage in a well-choreographed dance of highly saturated monochromatic color and geometric shapes. The irregular spacing of the triangular and trapezoidal forms, as well as the interplay of curved and straight edges create both a dynamic rhythm and perfect balance. Here, the wall itself begins to serve as the artist’s canvas, while the forms of the paintings appear as gestural marks on it, blurring the divide between painting and sculpture. At 11 W. 53rd St. (btw. Fifth & Sixth Aves.). Visit moma.org or call 212-708-9400.

Though the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum devotes most of its exhibition space to temporary special exhibitions rather than its vast permanent collection, it owns several works by the artist. One of the highlights is the square “Orange Red Relief” (1959), which is made of two joined, side-by-side panels of unequal depth.

![New York notes on Ellsworth Kelly (1923-2015) 3 Ellsworth Kelly: “Orange Red Relief, 1959” (Oil on canvas, two joined panels; 60 x 60 inches [152.4 x 152.4 cm], Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, NY, Gift of the artist, 1996, 96.4511). Image © Ellsworth Kelly, courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery/Guggenheim Museum.](https://www.amny.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/orageweb.jpg)

At the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Kelly’s “Spectrum V” (1969) consists of 13 panels, each measuring about 84 x 34 inches. Here, Kelly revels fully in a luminous palette that is worlds apart from the moodier shades preferred by the Abstract Expressionists two decades earlier. As he explained in a 2013 interview with Agnes Gund conducted for the Museum of Modern Art, in this work he reconfigured and recontextualized the sequence of colors found in a rainbow. However, in this case, yellow, which is usually at a rainbow’s center, can be found on the outside; we are moving from light to dark to light. While each panel exudes a totemic presence, grouped together they transform into a true environment, absorbing the viewer’s attention visually, as well as physically. At 1000 Fifth Ave. (at E. 82nd St.). Visit metmuseum.org or call 212-535-7710.

Currently, Matthew Marks Gallery is hosting a particularly interesting and unusual Kelly exhibition. Over 40 of his gelatin silver print photographs are on display, marking the first exhibition of its kind. The fact that Kelly finished preparing the prints and planned the exhibition shortly before his death makes this show especially enticing. Kelly started taking photographs with a borrowed Leica in the 1950s.

Because he used them to make notations of things he saw and subjects to draw, these photographs not only make for fascinating works of art, but aid in shedding further light onto his unique vision. In contrast to his sketches and collages, these photographs never served as preparatory studies for his paintings or sculptures. What they do capture is Kelly’s unique eye for the compositional possibilities of everyday details.

“Ellsworth Kelly Photographs” is on view through Apr. 30, at Matthew Marks Gallery (523 W. 24th St., btw 10th & 11th Aves.). Visit matthewmarks.com or call 212-243-0200.