This story was reported by Michael Dorgan, Christian Murray and Isabel Song Beer. It was edited by Robert Pozarycki

Kaseem, 66, peddles pot out in the open at Washington Square Park every day — one of more than a dozen vendors selling cannabis products at a circle of folding tables around the iconic fountain.

Despite the close competition, Kaseem says business has never been better.

“I make between $500 and $800 every time I come out here,” said Kaseem, who didn’t want to provide his name, while peddling cannabis at Washington Square Park earlier this month. “I come here with a $12 table—that’s it. I ain’t got no overheads, I’m the overhead….and I ain’t paying Uncle Sam a thing.”

The Washington Square Park vendors are selling a variety of items, from colorful gummies and lollipops—to joints, flowers and mushrooms. They sit behind tables that are brazenly signposted “weed” or have elaborate menus on display.

“Edibles, mushrooms, pre-rolls, check it out,” vendors can be heard yelling.

But who’s going to stop them? Marijuana’s legal in New York The money is good, and the enforcement is limited — so cannabis vendors are setting up make-shift stores in parks, on sidewalks and even bridges across New York City.

The cost of opening a brick-and-mortar dispensary—whether legal or not—makes no sense to these dealers. The cost of rent, hiring employees, needing security, and paying taxes are all issues they want to avoid.

New York State legalized cannabis two years ago, and although the law allows for personal possession of up to three ounces of cannabis, only nine stores in the state are licensed to sell it. All other sales are illegal.

Five of the nine stores licensed to sell cannabis are located in Manhattan, all within close proximity to Washington Square Park.

The street vendors, however, say they are not concerned about being busted, with law enforcement largely leaving them alone. Authorities, they say, are more interested in targeting the smoke shops and don’t want to go after the smaller operators.

Therefore, street vendors selling cannabis at parks and on sidewalks are ubiquitous.

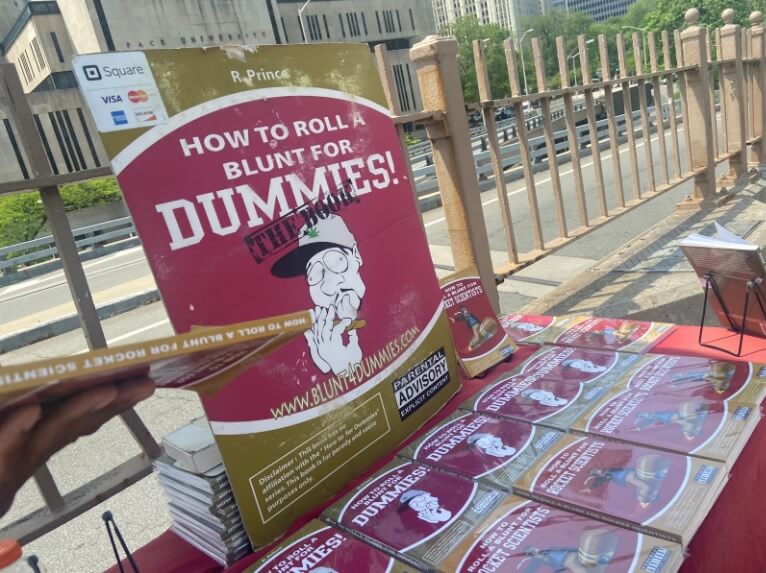

For instance, on the Brooklyn Bridge last week, a man who goes by the name R Prince had a foldable table set up and was selling cannabis, along with a friend. He says he also goes to Prospect Park to sell cannabis depending on the day.

“On a good weekend in one of the parks, we’re making like $500 each day—easy,” Prince said. “In the summer it’s even better, since there’s much more people out.”

Meanwhile, a vendor by the name of Kalief, had a foldable table set up on the sidewalk on Bedford Avenue in Williamsburg, and says he has been selling cannabis for the past nine months. He says his customers are mainly tourists and New Yorkers who just happen to be in the mood for marijuana.

Kalief said he operates out of parks and busy streets. He even provides customers with a product menu that can be accessed via a QR code. Customers can also pay for his weed through apps like like Zelle, CashApp or Venmo.

Not in their sights

Despite the proliferation of cannabis street vendors, authorities are placing little focus on street vendors, with the city and state more focused on shutting down illegal smoke shops.

The Office of Cannabis Management, the state agency that oversees the industry, is concentrating its efforts on storefronts that try to look like legitimate dispensaries.

“OCM is focusing on shutting down unlicensed shops masquerading as legal dispensaries, endangering public health and safety,” said Trivette Knowles, a spokesperson of OCM. “Our focus is not on your local neighborhood dealer. We don’t want to recriminalize cannabis.”

The OCM, which has its own enforcement team, typically works alongside the New York City sheriff’s office—and is part of the NYC Sheriff’s Joint Compliance Task Force.

The task force is headed by New York City Sheriff Anthony Miranda who told amNY Metro that the unit has largely been targeting storefronts, and that cannabis sales in parks would be handled by the NYC Parks Dept.

“The Parks Dept. would be the primary enforcement agency,” Miranda said, as to which agency would target illegal vendors at parks. “If they needed assistance, then we would obviously join them as part of a task force.”

The Parks Department, however, has not taken a hardline approach to enforcement. Instead, the department, which has Parks Enforcement Patrol (PEP) officers, is more focused on educating vendors that they are breaking the park rules than making arrests.

“Our PEP officers’ first course of action is to educate parkgoers to our rules; if not followed, the next step would be to issue a summons, and only in extremely rare circumstances would we effectuate an arrest,” said a Parks Department spokesperson.

The agency, when asked about cannabis activity in Washington Square Park, said that it was addressing the issue.

“We are collaborating with NYPD to address unauthorized vending and other conditions in Washington Square Park,” the Parks spokesperson said. “During recent combined operations, we have issued multiple summonses to vendors in violation of Parks rules. We will continue to coordinate with NYPD and adjust our approach as needed.”

The NYPD, in a statement, says that it addresses the illegal sale of cannabis and that it will “continue to work closely with the Office of Cannabis Management, prosecutors, and other criminal justice partners to address any unlawful activity relating to the sale and use of cannabis.”

But the vendors at Washington Square Park last week didn’t seem too concerned about enforcement. Many were smoking cannabis while selling, despite smoking being prohibited in city parks.

The cost of doing business

Kaseem, who has been selling cannabis at the park for two years, said that he has only had two run-ins with police since he has operated there.

On one occasion, he said he was brought to the NYPD 6th Precinct, located in Greenwich Village; his cannabis was confiscated, and he was issued with a fine. On the second occasion, he was fined — but his cannabis was not taken.

But those fines, he says, are just the cost of doing business.

“The next day I come out and make $700, Next day I make $900—so it balances itself out,” Kaseem said.

More often than not, he noted, if he’s approached by authorities, he usually just gets a warning.

“They will come around and tell you, “Yo, man, shut it down for the day.’ You got to respect that.”

He sells joints for $10 each, and bags of edibles and mushrooms for $40.

“Man, I make so much money I could go and live in another country right now.”

He didn’t say where he gets his cannabis from, just that he sells “high grade s..t.”

Kaseem said the cops are more focused on the smoke shops. “They’ve been knocking up the stores more than they’ve been f–king with us.”

Meanwhile, R Prince, who was operating on the Brooklyn Bridge, has never been arrested, although his operation is not quite as brazen as Kaseem’s. He sells “pamphlets” on how to roll blunts and joints, with each pamphlet sold at a different price based on the weed that will come with it.

Once a purchase is made, he directs them to a friend who then provides the cannabis.

“No one bothers us, and I think it’s pretty hush hush because we look like guys just selling books and we are wedged in between ladies selling fruit and jewelry,” R. Prince says about his operation.

Kalief, however, said he has been busted by cops twice and has had his goods confiscated a handful of times.

He said he doesn’t stay in the same spot and moves his table from location to location.

Kalief doesn’t view the legal dispensaries as his competition. After all, there are no dispensaries in Brooklyn currently licensed to sell it.

“Honestly, my biggest competition is these smoke shops that are popping up everywhere,” Kalief said. “Look up and down the street and you can see about three of them…”

Smoke shops targeted instead

Authorities have been making a big push to shut down illegal smoke shops, although they have a big job reining them in.

Miranda, whose office has between 135-150 officers, said that more than 1,400 storefronts are illegally peddling cannabis, a number that is continuing to grow.

“Our list is growing,” Miranda said. “More and more people are reaching out.”

Miranda’s office leads the Cannabis Task Force, which is comprised of officers from NYPD, the New York City Department of Consumer and Worker Protection and OCM. The Sheriff’s Office, he said, conducted 162 raids on unlicensed smoke shops from January to April. During that period, it made 46 arrests and issued 249 notices of violations.

Given the large number of store front operators, Miranda said that the task force has priorities, such as targeting stores where someone gets sick.

“We get a report of somebody getting sick as a result of something they brought from a store and that would probably be a priority location to go after,” Miranda said. “Anything that’s dangerous, we have to address…and then we also focus on those [stores] that are next to the schools, houses of worship, or near where the kids are.”

Miranda said that the cannabis that is being sold illegally on the streets and at smoke shops is often hazardous.

“It is dangerous what they are doing—they don’t know what THC is in their products. These people endanger lives,” Miranda said.

He said that many stores are also targeted based on public feedback. “A lot of it is received by complaints, intelligence from other agencies, and referrals from elected officials.”

Miranda said that the storefronts cannot be closed overnight, which frustrates many residents. He said that the alleged perpetrators have to go before a judge, who will make the determination.

“We have to explain that everybody is entitled to the due process of the law, right or wrong, that they have to have their day in court. And once they get their day in court and have the hearing, the judge determines what the next steps will be, what we’ll be able to do next,” Miranda said.

Miranda said all of these illegal operators — whether storefronts or street vendors — are hurting the city and making it harder for the legal operators to be successful, most of whom are justice involved and are small business operators. The state has reserved the first batch of licenses to applicants with cannabis convictions, as a means to give the victims of the war on drugs a chance to compete in the new market.

“They are robbing our community and robbing our city,” Miranda said. “We are finding these people are only interested in making a quick dollar and they don’t care what they are mixing into these products and who is in danger. They are putting everyone at risk.”

Read more: NYPD Ends Public Access to Brooklyn Police Radios