For nearly a century, the New York press and the public have had access to police frequencies, learning about breaking news throughout the five boroughs through scanner radios.

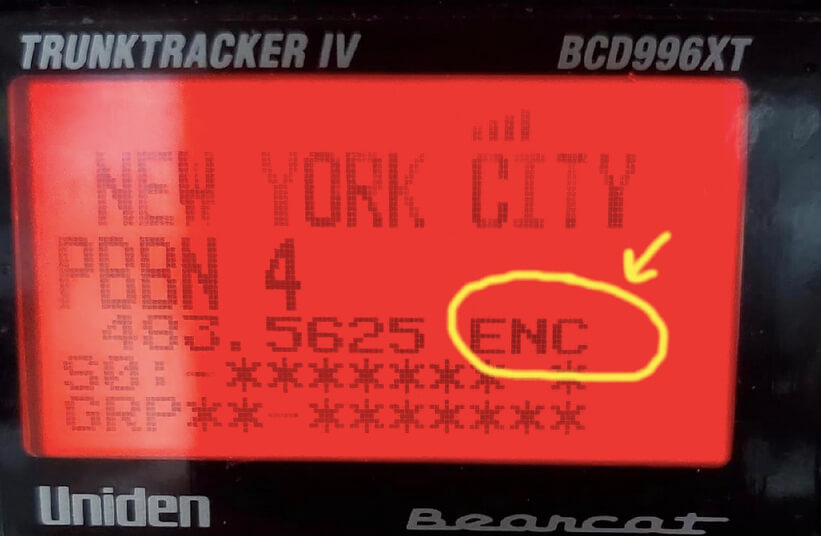

But that era of transparency, dating back to 1932, seems to be reaching the end, as six NYPD precinct radio frequencies serving northern Brooklyn suddenly went dark on July 17 — the officers’ radios being converted to “encrypted” channels that shut the public out of police communications.

As a result, no one but the officers on duty in the six Brooklyn North precincts knows what’s happening in those areas in real-time. That includes the press, endangering their ability to independently report on breaking news such as active crime, collisions and even police-involved shootings or assaults.

And NYPD officials have indicated there is “no plan as yet” to include the media. This comes amid rumblings from police insiders that the all-important Special Operations radio channel, which every major media outlet uses to cover citywide incidents, may be next to be fully encrypted — and the entire NYPD radio network could be fully encrypted by late 2024.

NYPD insiders indicated that they believe the endeavor to encrypt police channels stem from an attempt to stay one step ahead of criminals who could be using scanners to listen to police activity. Still, it is unclear how prevalent such a practice has become.

amNewYork Metro also quizzed newly minted Police Commissioner Edward Caban on the transition. He maintained that the process is still in the testing phase.

“We are always going to use technology to make sure all of us are safe,” Caban said. “Right now it is just in the testing phase, nothing has gone forward. That’s where we are at right now, it’s still in a transition phase.”

Still, the move to encrypt some police frequencies may also be a political one.

Elected officials in the past, including Mayor Eric Adams, said they would listen to the media concerns, but have yielded no results. But one City Hall official, who wished to remain anonymous, said the mayor is on the outs with the media and “he doesn’t like the optics of crime in the media.”

“Whether crime is up or down, if the press shows photos of people being shot, stabbed or robbed, it gives a bad impression of the city and so the mayor would prefer to limit those photos,” the official said.

Media organizations are fearful of the repercussions of being shut out from NYPD frequencies, saying encryption removes a key ability of the Fourth Estate to hold the police accountable.

“I’ve been working in the streets 38 years and this is going to kill the spot news photographer and pretty much force people into retirement if they encrypt,” said Bruce Cotler, president of the New York Press Photographers Association. “The whole thing is they are covering it up, and there will be no transparency in an administration that says there is. They were not truthful with us – they already had a plan in effect and we were not part of it.”

Half-truths about encryption plan

For years, the NYPD has been working to upgrade and modernize their aging communications systems — spending more than half a billion dollars on radios, transmitters and repeaters installed around the city.

Repeated attempts by amNewYork Metro to get detailed information on how those funds were spent have been rebuffed 10 times in the past year, with the NYPD maintaining that such information is “secret.”

NYPD officials had repeatedly assured the leaders of nine journalism organizations across the city (known as the NY Media Consortium) that radios would not become “encrypted” until late 2024, at the earliest. In the past, the NYPD argued for encryption and modernization of systems because members of the public have used radio transmissions for alleged nefarious reasons or have attempted to interfere with communications. They also argue that this is a “public safety issue.”

But everything changed with the Brooklyn North precincts effectively cutting themselves off from the public on July 17 of this year.

The precincts where officers are now using encrypted radios include the 90th and 94th, covering Williamsburg and Greenpoint; the 81st and 83rd, covering Bushwick and Bedford-Stuyvesant; and the 84th and 88th, covering Brooklyn Heights and Cobble Hill.

Advocates and media members say full radio encryption would leave the NYPD in virtually full control of the narrative.

Stories such as the Eric Garner choke-hold death on Staten Island, and high-profile police shootings resulting in the deaths of Sean Bell in Queens and Amadou Diallo in Harlem, may not have been known without the ability to monitor communications.

Police narratives of deaths involving civilians in their custody — such as the murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis in 2020 — was among the topics raised this past year on HBO’s “Last Week Tonight with John Oliver” in a segment on crime reporting in America, and how journalists often rely only upon police information — though police don’t always provide the entire story on a given event.

Other cities around the country have been upgrading radios and some have already encrypted. When the media and public protested, some cities’ police departments agreed to provide access — but delayed the signals by many minutes.

Baltimore, MD and Louisville, KY caved to public pressure and gave the media a Broadcastify app set to a 15 minute delay. Chicago has a 30 minute delay, though the administration there claims they will shorten it.

‘An infringement’ on media rights

Many media organizations have blasted the NYPD for shutting down radio traffic to the public in Brooklyn North, while others are taking a wait-and-see approach.

“Encrypting police radios and stopping reporters from hearing important news of crime and emergencies is a danger to the First Amendment and to the safety of New Yorkers,” said Debra Topetta, president of the New York Press Club. “These restrictions on practices that have been in place for almost a century are nothing but an infringement on the rights of the media and the public. We have conveyed these thoughts to the NYPD and the mayor’s office on numerous occasions to no avail.”

Past President Jane Tillman Irving was more blunt: “They lied to us as usual and are not to be trusted – clearly they don’t want us to have access to breaking news and that’s really dangerous. They said they would cooperate, but this is very disheartening.”

“We need elected officials to know what is happening – constituents need to know that the NYPD doesn’t care,” said Colin Devries, past president of the Society of Professional Journalists, Deadline Club. “They (the NYPD) don’t want communications easily accessible. If the NYPD is trying to rebuild trust with the public, this is not the way to do that to become less transparent and limit communications – creating an unsafe environment in the city.”

General Counsel Mickey Osterreicher representing the National Press Photographers Association (NPPA) issued a statement expressing extreme “disappointment” that the encryption occurred in Brooklyn “despite assurances from NYPD executives that” it “would not be happening for some time.”

“This, after we met with them in good faith to express our concerns over how encryption will negatively impact the ability to cover matters of public concern in a time critical manner, which will ultimately impact the public’s First Amendment right to be informed,” Osterreicher said.

Diane Kennedy, president of the New York State Publishers Association, said shutting radio transmissions is a safety issue.

“I think it’s important for the safety of journalists and the general public to have access to police communications in real time,” she said. “Journalists who are racing to cover an event need to know what they are walking into and also, need to be able to inform the public immediately to tell where to people should avoid if there is a public safety issue in the area.”

Other groups were still cautiously optimistic that a deal could be worked out, including Dan Shelly, president of the Radio Television Digital News Association (RTDNA). Shelly has been tracking other areas of the country and assisting local media in their negotiations with their departments.

“RTDNA remains hopeful that the NYPD will put transparency over secrecy,” Shelly said. “The NYPD and journalists both serve the same public, they may do it in different ways, but they do it better together whenever it is possible. Secrecy and lack of transparency doesn’t serve the citizens of New York well.”

Political and NYPD response

The Consortium is seeking the intervention of Deputy Mayor for Public Safety Phil Banks, but has not yet heard back from him.

The New York City Council approved more than $100 million in the NYPD budget this past spring for police communications, but failed to question what they planned to do on encryption. Council Speaker Adrienne Adams had promised to look into the issue, but did not respond for comment.

Public Advocate Jumanne Williams, a frequent critic of the NYPD had blasted the police plan to encrypt, calling it “terrible.” After three days of repeated calls and emails, his office also did not respond.

The mayor’s office asked for additional details and after seven emails and three days of calls, they responded, “Please contact the NYPD’s press office.”

The NYPD press office, however, did not provide direct answers to questions about encryption, except to say, “Everything the NYPD does is with the public’s safety in mind.”

Assembly Member Jessica Gonzalez-Rojas, attending an actors guild picket line in Manhattan Wednesday, questioned the need for secrecy.

“I believe we have a responsibility to the public – if this is something the press and the public had access to, it should remain such. We need greater transparency so this is deeply problematic and needs to be investigated,” Gonzalez-Rojas said.

With reporting by Dean Moses

Read more: Fifth Arrest Made in Fatal Chelsea Shooting