New York lawmakers have until Friday to vote on the “Keep Police Radio Public Act” to prevent the NYPD and other police departments from shutting the press out of police radio access amid encryption efforts.

The legislation would provide credentialed media access to encrypted police radio channels, and compel the NYPD to allow access to New York City media that have listened to police radio channels as a source of news.

The bill, introduced in the state Senate by Mike Gianaris of Queens and picked up in the Assembly by Karines Reyes of the Bronx, must be passed by both houses on Friday, the end of the current legislative session in Albany. If it doesn’t pass, it will have to be reintroduced next year.

Reyes expressed cautious optimism that the bill would move forward.

“We are trying to get it through the Assembly, but it never came out of committee. We are trying to reference it to rules,” she said. “It may be moving in Senate, but the Senate committee had questions on the bill. We tried to get them answers. We believed it to be straightforward, but there must be a willingness to move it.”

NYPD officials have opposed the bill; in the past, they have questioned the vetting of journalists credentialed by the Mayor’s Office of Media and Entertainment, and police officials were seeking a delay in radio transmissions.

The NYPD has yet to provide a plan for keeping the media in the loop to maintain transparency, despite their billion-dollar radio upgrade being in its sixth year. NYPD officials said they planned to have a plan “after the encryption program is completed,” by late 2025.

In the meantime, seven more precincts in Brooklyn were encrypted last week — encompassing much of Brooklyn South areas. All eight Brooklyn North precincts were encrypted in July 2023, and four Staten Island precincts went dark back in March.

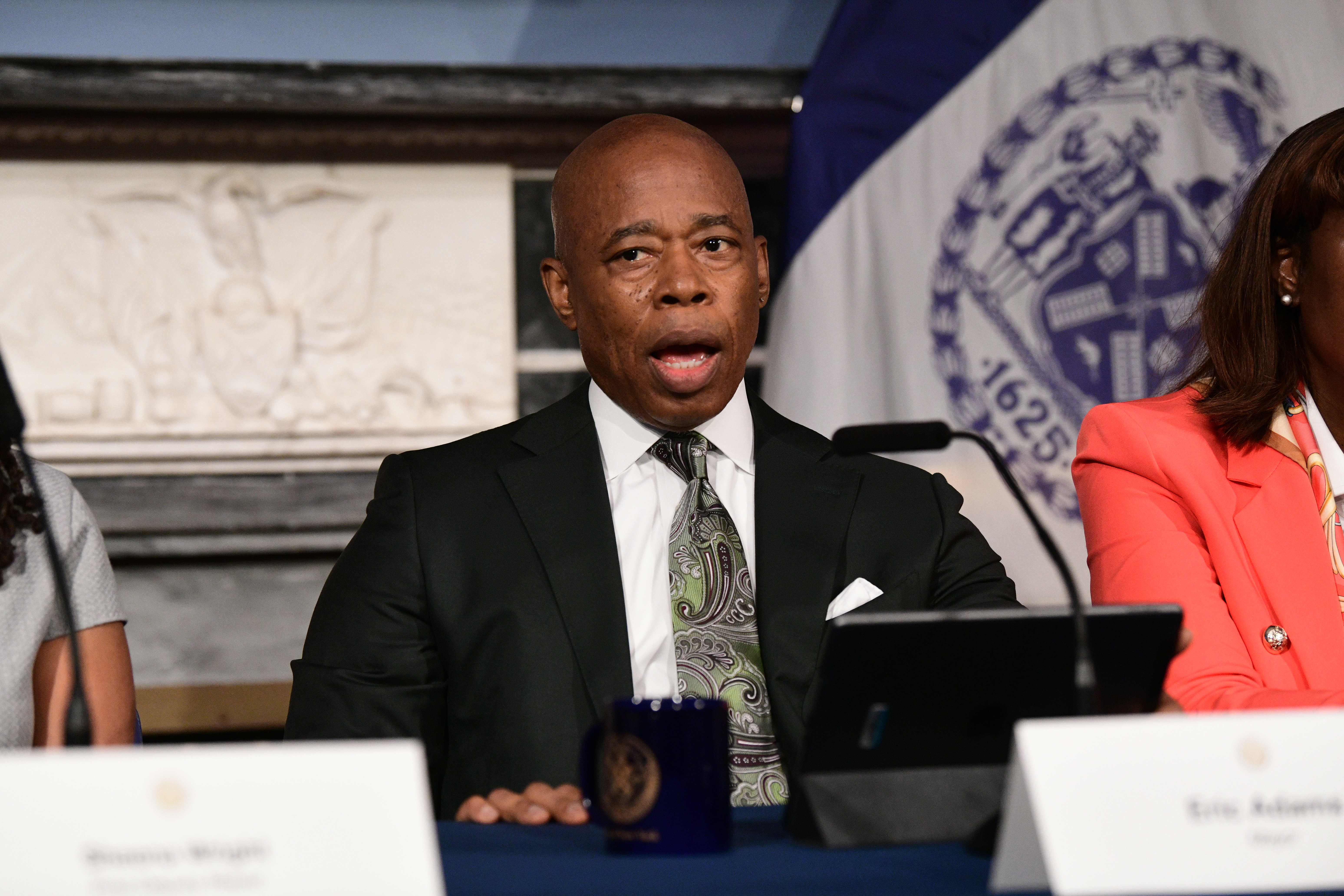

Mayor Eric Adams, while not saying he is opposed to the bill, expressed reservations at a press conference on Tuesday at City Hall.

“My biggest concern, I’ve said this over and over again, bad guys get access to this information. You know, bad guys that commit crimes,” Mayor Adams said. “This technology, if not used properly, it could be harmful. If you know [that] a police officer is responding, how they responded, how they communicated, we need to get it right. I think we can find the right balance. The New York City Police Department is going to do that.”

‘The NYPD then controls the narrative’

Recently, members of the News Guild, part of the Communications Workers of America, proclaimed support for the bill, citing transparency and press access. They joined a chorus of support that includes the New York Media Consortium, a group made up of eight press organizations. However, some Guild members have expressed dismay that only the press, not the public, would get radio access in the bill.

Diane Kennedy, president of the New York News Publishers Association has been at the forefront of the effort.

“As encryption of police radio communications spreads across New York City, the number of city residents losing access to real-time independent reporting on breaking news events is rising,” Kennedy said. “Legislation by Senate Deputy Majority Leader Michael Gianaris and Assembly Member Karines Reyes could roll back NYPD’s work to bring 90 years of journalists’ ability to monitor police communications to a halt, but only if the state Legislature passes the bill before adjourning later this week.”

Bruce Cotler, president of the New York Press Photographers Association also expressed hope that the bill would pass muster.

“More and more, police precincts are going dark, leaving the media who depend upon the ability to know what goes on in the city, in the hands of the NYPD,” Cotler said. “The NYPD then controls the narrative, and then will be able to decide what is news and what is not. That was our job. We must have transparency or checks and balances will be gone.”

The New York Media Consortium has sought out help from the City Council, including Speaker Adrienne Adams, who was critical of the NYPD for dragging their feet on including members of the media in communications.

At an NYPD budget hearing, Chief of Information Technology Ruben Beltran said there were “operational reasons and real concerns for security” that require the radio transmissions to be encrypted. He told the Council that the NYPD made 55 arrests in 2023 for unlawful possession of radio devices, and read off a list of arrested suspects. None of those were members of the media.

The Speaker was asked whether she or the council plan on taking up the issue should the legislation fail. She did not comment when asked about the issue on Tuesday.

During the March budget hearing, Speaker Adams said, “There should be a happy medium here…than throwing the baby out with bathwater.” However, the Council has still not taken any action to maintain transparency even as the NYPD came to the Council seeking an additional $81 million for more radios.

A spokesperson for the City Council issued a statement Wednesday:

“We support the state legislature advancing a solution to maintain the transparency that is being threatened by efforts to encrypt all radio communication, which would have a negative impact on volunteer first responders, accountability and public safety.”

In the past two weeks, 9,000 new radios arrived from Motorola in a no-bid contract.

The legislation would affect other police agencies who have already encrypted their radios, including the Nassau County Police who have been encrypted for several years, leaving Long Island media in the dark. In the meantime, the NYPD currently informs the press of breaking news hours after occurrence, or not at all.

Should the bill fail, Kennedy noted, it will be difficult to resurrect and give the press a lifeline into police communications.

“Once the radios go dark, it will be hard to reopen them again,” she said.

Mickey Osterriecher, chief counsel for the National Press Photographers Association said a failure to pass the legislation will have a negative national effect as other departments evaluate their encryption policies.

“Other major cities are looking to New York to see what happens here – if the NYPD is able to encrypt all radios, without any consideration for transparency or accountability, that is only going to encourage other cities to do the same,” Osterriecher said. “What’s unfortunate, is news organizations can care less and we can’t make them do anything.”