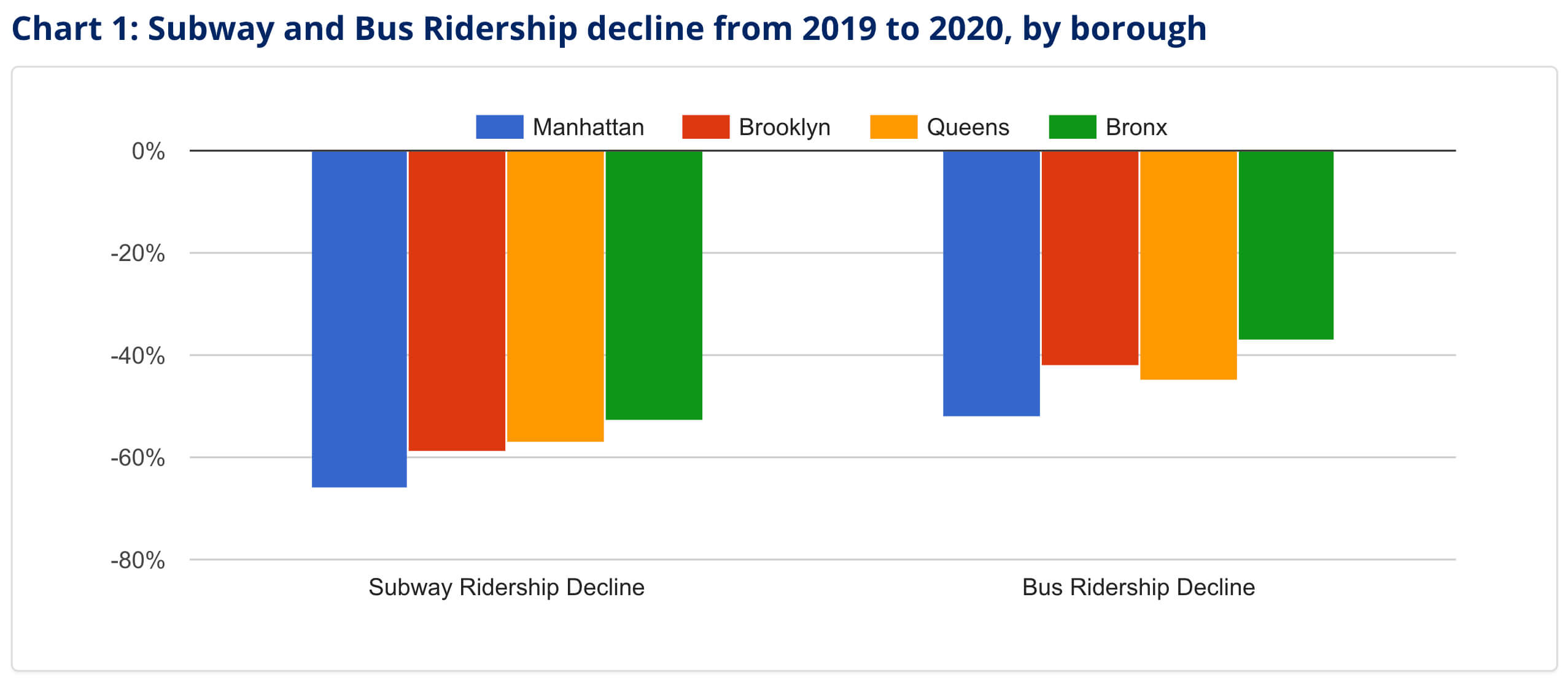

Commuters outside Manhattan and those riding the subways and buses in the early morning hours were more likely to stick to public transit during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, according to a new analysis that City Comptroller Scott Stringer released Sunday.

Subway ridership among Manhattanites dropped by 66% in 2020 compared to 2019, while the decline in the more working-class Bronx was only 53% during that time, according to the Oct. 10 study by the city’s fiscal watchdog who called on MTA to boost service to meet changing travel patterns.

“We have new data that proves what our frontline workers and working families have known all along: rush hour is not nine to five, Monday through Friday, rush hour is 24 hours a day, seven days a week,” Stringer told reporters at the 72nd Street station on the Upper West Side.

Early morning subway traffic between 5-7 a.m. saw the smallest dip in ridership year-over-year at 48%, while the buses only had a 32% decrease.

Morning peak ridership from 7-9 a.m. dipped 65%, more in line with other times of day, the data show.

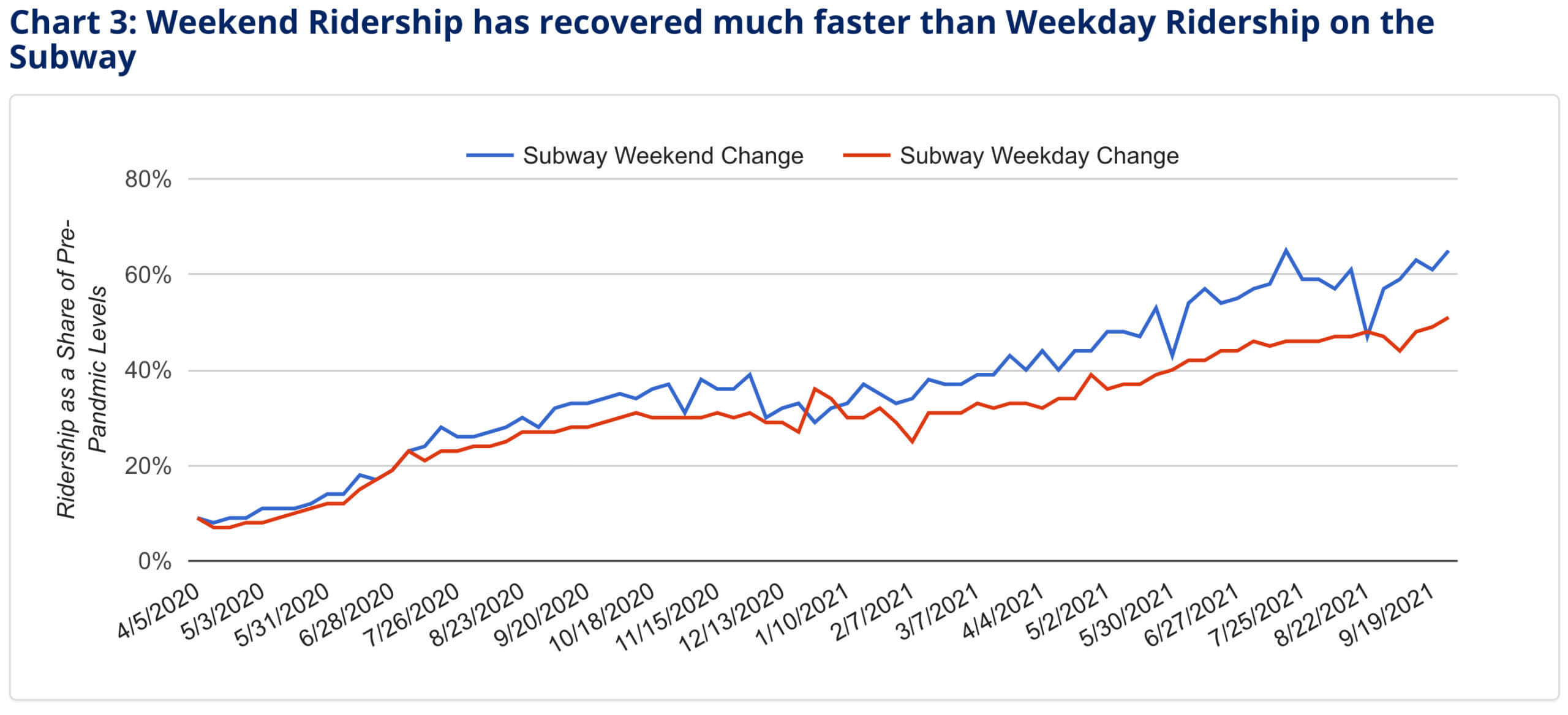

More recently, weekend ridership on the subways — or “discretionary” trips as MTA calls them — rebounded quicker than other figures, reaching 65% of pre-COVID levels, compared to 51% on weekdays as of September 26, 2021.

But MTA financial bigs have warned that they will have to cut service through “right-sizing” by 2023 when they run out of $14.5 billion in federal COVID relief funds.

Stringer, who unsuccessfully ran in the Democratic primary for mayor and will be out of office come Jan. 1, 2022, said the Authority should funnel funds to boost service to every six minutes all day every day, as less people commute during the traditional rush hours.

“The MTA needs to step up, there’s no excuse. All subways and high ridership buses should arrive at least six minutes throughout the day, seven days a week,” he said.

To fund this, Stringer called on the state’s Department of Taxation and Finance to rejig its tax on employers doing business in the city and surrounding counties, known as the metropolitan commuter transportation mobility tax.

Currently, the state sends two-thirds of these tax revenues roads, bridges and maintaining outdated highways, and one-third to public transit, but Stringer wants to flip those allocations, so that trains and buses get the larger share.

The politician also urged Congress to pass the so-called Stronger Communities Through Better Transit Act by Georgia Rep. Hank Johnson, which promises to deliver $3 billion in annual funds to the MTA’s operating budget for four years, along with a yearly $17 billion for other transit agencies around the nation.

Stringer acknowledged that running such frequent service will be challenging in the short term as MTA still reels from crippling crew shortages caused by pandemic-era hiring freezes, retirements, and 171 transit workers dying of COVID-19, all of which has led to lengthy delays between trains.

Transit bigs have tried to bring crews back and expand class sizes for conductors and train operators to plug the gaps, but Stringer said the workforce deficits shouldn’t stop the agency from planning for better times.

“This crisis should not be an excuse if we’re doing the long-range planning that will bring us into a 21st century transportation system,” Stringer said. “If you don’t plan for it, prioritize it, and align the money with our six-minute goal, you know what’s going to happen, it’s going to go into the black hole at the MTA and we’re never going to see it again.”

Also on Stringer’s wishlist is for the city’s Department of Transportation — which controls the streets — to paint 35 miles of new bus lanes and busways each year, up from the 20 miles planned by DOT and MTA for 2022.

DOT spokesman Seth Stein said in response: “We agree that it is essential to improve mass transit, helping us reduce congestion and get New Yorkers out of their cars. We are moving full speed ahead on bus lane projects around the city, and are always looking to do more.”

Stringer also wants the MTA to reopen shuttered station entrances and the city to up-zone land near mass transit stations to allow for more affordable housing development.

An MTA spokesman highlighted the agency’s returning service in recent months, and said ridership will get a boost from a slate of projects under the Authority’s current five-year capital program, including plans to install more station elevators and expanding commuter rail service with the Penn Station Access and East Side Access projects.

“The MTA has increased service in recent months on both commuter railroads and New York City Transit has continued to run more than 90% of subway and bus service for roughly 55% of pre-pandemic customers,” said Aaron Donovan in a statement. “We recognize the critical role the MTA plays in recovery of the region’s economy and have announced exploration of new fare options while continually providing better service with resources available.”