BY STEPHANIE BUHMANN | Fewer than three weeks into its run at the Whitney Museum of American Art, Frank Stella’s retrospective has already been widely reviewed by the media. With over 60 works — some of them massive — filling its entire fifth floor, it is the perfect project to highlight the museum’s new lofty premises. Although often too closely installed, the many paintings, wall reliefs, maquettes, free standing sculptures and a few drawings provide insight into Stella’s versatile, nearly six decade-spanning oeuvre.

As one of the most influential American artists working today, he certainly deserves such attention. And yet, what is interesting about the extensive coverage that this exhibition heralds is its common tenor: it is still Stella’s early work that remains the most universally revered and better understood.

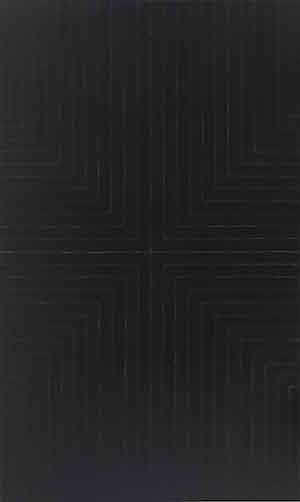

Even Stella himself has noted in the recent past that his so-called “striped” paintings might be the best he has ever painted. In fact, it was his Black Paintings that put him on the map. Works such as “Die Fahne hoch!” (1959) are straightforward compositions, which assemble even stripes of house paint into parallel geometric movements. They are often described as emotionally detached, and considered a historic bridge between the romantically charged Abstract Expressionist works of Jackson Pollock and Franz Kline and the Minimalism of Donald Judd or Carl Andre.

“What you see is what you see,” Stella once remarked about these works — but that is too simple a description. It is true that they focus on the surface and do not veil a hidden mystique, but they are also elegant contemplations of rhythm. In that, the austere aestheticism of their vocabulary pulses with life within.

In the early 1960s, Stella applied the concept of the Black Paintings to compositions based on aluminum radiator paint, which Pollock before him had used to strong effect as well. In works like “Union Pacific” (1960), the reflective silver surface makes for subtle plays with light. Depending on the viewer’s position, it either shimmers or appears somewhat muted. The paint handling enhances this effect: Stella changed the angle of his brush as he turned corners, allowing the light to reflect differently and to animate the surface.

Both the Black Paintings and the Aluminum Paintings keep the viewer at a distance, encouraging them to be studied from afar. They manifest as statements rather than transformative experiences and this quality is characteristic for all of Stella’s work. The paintings and sculptures are created and meant for their own sake, and especially for the experience of making them. They are not intended to become catalysts for something emotional or spiritual.

Born in 1936 to first-generation Sicilian immigrants, Stella grew up in a suburb of Boston. In 1954, he entered Princeton University, where he studied with the painter Stephen Greene, among others, and created gestural works with a muted palette that, above all, celebrated the spirit of Abstract Expressionism. After graduating in 1958, Stella settled on the Lower East Side of New York, where he soon acquainted himself with some of the major artists of the scene. At this point he became especially taken by Jasper Johns’ flag paintings. In this context, Stella managed to rise quickly.

In 1959, he joined Leo Castelli Gallery, which also represented Johns, and exhibited in “Sixteen Americans” at the Museum of Modern Art (1959-1960). He became a bona fide shooting star to the extent that the Museum of Modern Art organized a survey of his work in 1970 when he was not even 35 years old. Despite this early success, he managed to stay clear of wanting to please and meet others’ expectations. In fact, his work has so continuously and drastically changed over the decades, that he was sure to lose many of his early admirers along the way.

In the mid-1960s, the striped paintings led to the Irregular Polygon series, which broke away from the strict organization of his previous work. In “Conway I” (1966), for example, thick stretcher bars push the composition off the wall. Both its vibrant palette and physicality provoke a sense of confrontation. Stella made 11 Polygons, as well as identical canvases for each, employing different color combinations every time. In these works, a thin line of raw canvas delineates each color field, albeit without mechanical precision. Bleeding color makes for irregular edges when viewed up close.

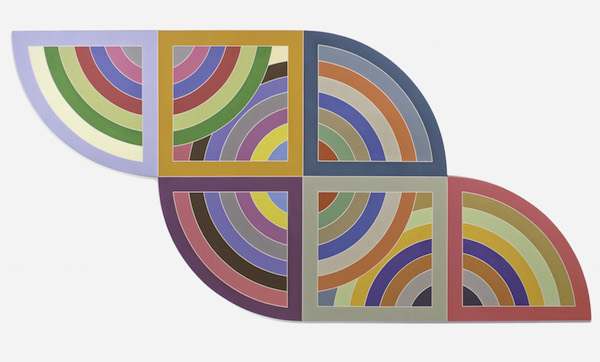

Despite their overt graphic quality, the Irregular Polygons convey a sense of playfulness that foreshadows Stella’s sculptural works of the 1990s and 2000s. The Protractor series came next, inspired by and named after the drafting tool used to draw and measure curves. When viewing works like “Harran II” (1967), Stella’s minimal palette of the Black and Aluminum Paintings seem a faint memory, even a foreign concept. Now, radiant and fluorescent fields of color dominate and establish a strong dynamism. They are organized in eight-inch bands that form rhythmic sequences of echoing arcs. Arranged side-by-side within square borders, they find unison in full and half circles.

Though Stella’s Polish Village series of 1970 — in which he collaged paper, felt and wood onto canvas — marked a turning point toward the more three-dimensional, his first truly sculptural works appeared in 1982. Stella has often remarked how his sculptures remain rooted in painting, but that the complicated forms he pursued demanded an independent physicality. They were, so Stella built paintings that he could then color and decorate.

When viewed frontally, “The Blanket (IRS-8, 1.875X)” (1988), might evoke the shape of a vertebra. It is the particular colorization of different sections that defines them, but also visually flattens the protruding three-dimensional form when viewed from afar. In fact, it is a hybrid, a painting with sculptural tendencies. Though one cannot study it in the round, which makes it less sculpture than painting, its carefully painted sides in fluorescent rainbow stripes leave no doubt that this work is not solely to be considered from the front.

As much as Stella has changed over the decades, one aspect remains the same: he has both openly admired other artists’ work and channeled it into his own. Pollock, Kline, Johns and John Chamberlain are perhaps the most evident. In recent years, Stella has openly dedicated whole bodies of work to literary and musical sources of inspiration. While the sonatas of Domenico Scarlatti and the writings of the American 20th-century harpsichord virtuoso Ralph Kirkpatrick, who made them widely known, inspired his Scarlatti K series, his most extensive series — Moby-Dick — ponders Herman Melville in depth. Then there are the tributes to a singular artist, like Kazimir Malevich in “Circus of Pure Feeling for Malevich” (2009), or to specific works of art, like Théodore Gericault’s masterpiece of (almost) the same title, in “Raft of the Medusa (Part I)” (1990).

At the Whitney, the chronological organization becomes looser as the exhibition unfolds, mixing works from different eras in close proximity. This unfortunately feels like a forced reunion, as if to remind us that despite all their drastic changes and differences, these works belong and can hum together. However, a strictly chronological curation might have been more effective, because the beauty of Stella’s oeuvre is its dissonance. Each body of work might have emerged organically from the previous, but it quickly strove for independence.

The fact that Stella has not spent his life echoing his most successful work from many decades ago, makes him inspiring. It will also ensure him credibility going forward, as his work will continue to impact subsequent generations of artists for entirely different reasons.

“Frank Stella: A Retrospective” is on view through Feb. 7, 2016 at the Whitney Museum of American Art (99 Gansevoort St., btw. 10th Ave. & Washington St.). Hours: 10:30 a.m.–6 p.m. on Mon., Wed., Thurs. & Sun and 10:30 a.m.–10 p.m. Fri. & Sat. Admission: $22 ($18 for students/seniors, free for members and those under 18). Visit whitney.org.