BY ROSE ADAMS

Three weeks after the police killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis, protests continue to sweep the streets of New York City — with young, Black New Yorkers on the front lines.

The demonstrations, which have already pushed the state to pass a package of police reforms, have been largely orchestrated by a new generation of local activists fed up with racial injustice, protest organizers said.

“I can definitely see other teenagers [marching], other Gen Zs, and you can just tell how much passion is driving them,” said Nia White, a 17-year-old Brooklynite who volunteers with an activist group called Freedom March NYC. “Gen Z is not the generation to mess with.”

The young upstarts have worked collaboratively to organize many of the city’s recent rallies, and have advertised their events on Justice for George Floyd NYC, a growing Instagram page which blasts a daily list of protests to more than 200,000 followers.

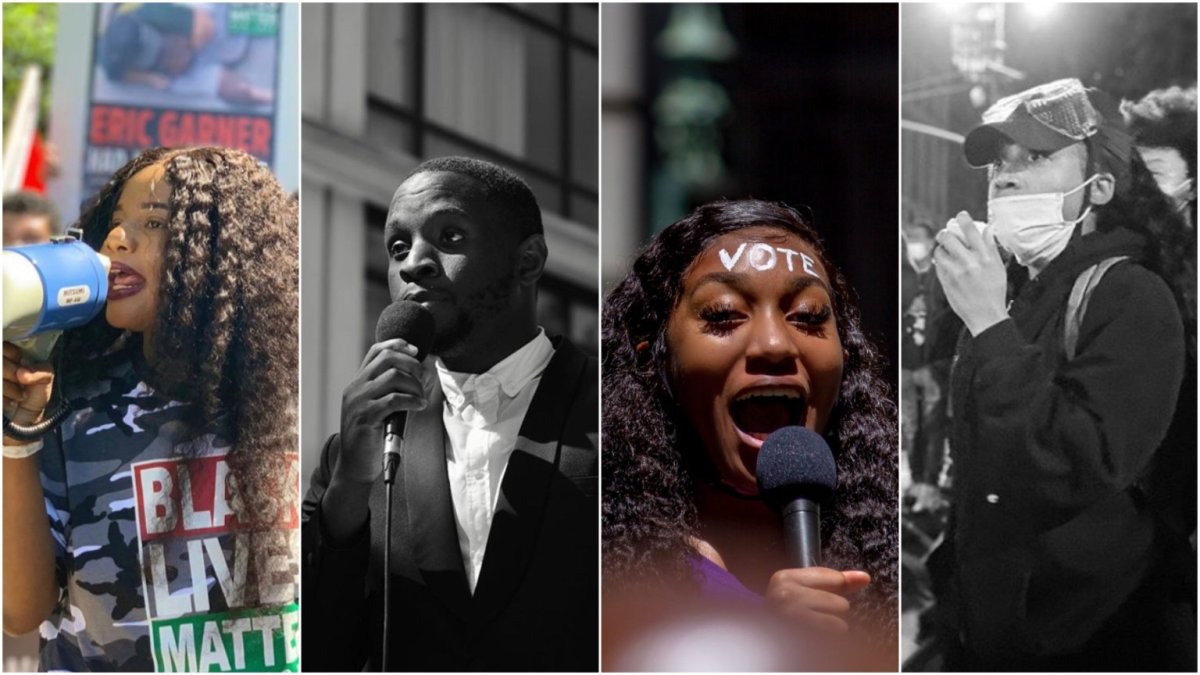

Meet some of the organizers behind the city’s largest protests.

NUPOL KIAZOLU

Nupol Kiazolu, the 20-year-old president of Black Lives Matter Greater New York, has organized some of the largest George Floyd protests in the city — including a march on June 2 from Bryant Park to Trump Towers that drew more than 15,000 people.

The march was non-violent — just as all of Kiazolu’s protests have been — but Kiazolu clarified that while she does not believe in violence, she doesn’t advocate for peaceful passivity, either.

“I’m not peaceful,” Kiazolu told Brooklyn Paper. “When I say, ‘No justice, no peace,’ I mean that.”

New York City’s Black Lives Matter chapter does more than organize demonstrations, Kiazolu said. The group also drafts legislation, hosts a youth coalition that teaches young people to be effective organizers, and runs a political action committee that supports grassroots candidates.

“Black Lives Matter, we don’t just protest, we work behind the scenes and the front lines,” she said.

Kiazolu had her first brush with activism when she was just 12 years old, after a neighborhood watchman killed 17-year-old Trayvon Martin in Florida.

“His murder really ignited a fire in my heart that I’d never felt before,” she said.

Kiazolu held a silent protest at her middle school in Georgia, where she and other students wore hoodies to protest his killing, she said. Teachers sent her to the principal’s office and wrote her up for detention, but her math teacher — a Black woman — stood up for her.

“This woman literally risked her job by walking down to the principal’s office with me with her hoodie on in solidarity,” Kiazolu said. Thanks in part to her teacher’s advocacy, the principal allowed Kiazolu to research her first amendment rights as a student to prove her right to protest, which she did. “At that point, I knew being an activist was my calling.”

Now, Kiazolu is a student at Hampton University, where she studies political science and pre-law. She plans to become a civil rights lawyer and politician. And while balancing her school work, career ambitions, and activism isn’t easy, she says it’s worth it.

“Time management and working with my team is what keeps me afloat,” she said.

CHELSEA MILLER

Chelsea Miller, a 23-year-old Brooklynite, co-founded the advocacy group Freedom March NYC after noticing a critical lack of oversight at one of the first New York City protests following Floyd’s death.

“When I went out that Saturday night, what I saw was really disheartening,” she said. “What I saw on the ground was that there wasn’t leadership.”

The next day, Miller and her good friend Nialah Edari worked tirelessly to organize a protest that night, which drew hundreds of people. Soon, Freedom March NYC began hosting larger events — including a massive June 4 march which led thousands of protesters from George Floyd’s memorial service in Cadman Plaza to Washington Square Park.

“That was one of the most memorable and significant marches,” Miller said. “There were thousands of people who crossed that bridge, it was non-violent … it was an incredible moment.”

The Brooklyn native said her experience growing up in Flatbush with a single mother played an important role in her activism.

“My activism has been informed by being a first generation American, by being raised by a single mother,” she said. “For me, my mom has always instilled in me a resilience and an understanding of your power and your voice, especially as a Black woman.”

Miller’s mother worked for many years at a foster agency, but eventually left the industry and decided to turn the second story of their family home into a group home for girls, Miller said. “I grew up with foster sisters and the stories of their experiences in the foster care system,” she explained. “To me, being able to turn the blinders to other people’s experiences is something I cant do.”

The experience inspired Miller to co-found a mentorship program as a student at Columbia University. The program, called Women Everywhere Believe, provides training sessions, resources, and events for young girls of color.

“I remember being in college and there were a lot of protests going on and feeling as though my voice wasn’t being heard,” Miller said. “So we created Women Everywhere Believe because we realized that Black women were not being centered in the conversation about police brutality.”

CHIBUEZE EZENYILIMBA

Chibueze Ezenyilimba, a 23-year-old Queens native, said he and his friends were inspired to host a march after hearing President Donald Trump deride protesters and call them “thugs.”

“My friend and the co-founder of the Black Tie Walk, his name is Keith, he posted a video of a couple African-American men dressed nice and walking down the stairs,” Ezenyilimba said. “I was like, ‘We should do that.’ We should dress down, show excellence and that we’re not thugs — try to change that narrative.”

The group decided to hold a march — dubbed the Black Tie Walk — on June 5 from Fort Greene Park to Prospect Park to protest police brutality and combat racist stereotypes. To Ezenyilimba’s surprise, he said, hundreds of people showed up.

“As we walked, we picked up people,” he said. “I’d say by the time we reached our destination we had upwards of 1,000 people with us. It ended up being huge.”

While organizing protests with Black Tie Walk is Ezenyilimba’s and his friends’ first experience with activism, the organizers say they have had plenty of negative run-ins with police.

Ezenyilimba said that when he was young, he witnessed police officers stop and frisk his 11-year-old brother, who was exceptionally tall for his age, while the two were waiting for their mom to pick them up from a playdate.

“We didn’t really see much to it because we were younger,” he said. “But then when you’re older you start to realize that’s not acceptable.”

Routine abuses combined with the deaths of many Black Americans at the hands of police have exasperated young Black Americans, Ezenyilimba said, sparking the present-day protests.

“Its the generation we’re apart of. Everybody’s just tired and fed up,” he said. “We were taught in school that our ancestors, our grandparents, this is what they walk for. This is what they were doing, and now the fact is that we have to do it as well, like nothing changed, is crazy.”

NIA WHITE

Nia White, a 17-year-old from East New York, said she never guessed she would be at the forefront of a social justice movement as a senior in high school.

“I definitely did not see me in this position now, I never expected to lead thousands of people over the Brooklyn Bridge,” she said. “I thought I was going to be at prom. I thought I was going to be graduation.”

White has spent her spring semester organizing rallies and drafting policy proposals with Freedom March NYC. Last week, the group released its policy platform for 2020, which pushes for a number of police reforms, White said.

“One of the [policies] I find most important because I’m young is getting police officers out of schools,” she said. “It would definitely help with the school-to-prison pipeline, and we feel it’d also help the education system.”

White said she began volunteering for organizations advocating for Black women after getting rejected from several internships and realizing how few Black women there were in leadership roles.

“I didn’t see anyone who looked like me,” she said, explaining that she was routinely rejected from internships at law firms and political offices. “I wouldn’t get the positions, and I feel as though it definitely was because I already had two strikes against me already — I was Black, and I was a woman. And then my third was that I was young, so it was automatically, ‘You’re out.’”

White has interned for Chelsea Miller’s advocacy group Women Everywhere Believe (WEBelieve) and for Black Women’s Blueprint, an organization that hosts workshops and advocates for policies on behalf of Black women. Both experiences have helped fuel White’s activism, she said.

“It gave the skills to speak up and the information as well,” White explained.

White, who plans to work in politics in the future, said that growing up in East New York also gave her the tools to call out injustice.

“In Brooklyn you always see these types of violent actions happening, and it definitely forms you,” she said. “Brooklyn is definitely the reason I have my voice today because no one in Brooklyn is silent. Everyone in Brooklyn speaks up. That’s just how my neighborhood conditioned me.”

This story first appeared on brooklynpaper.com.