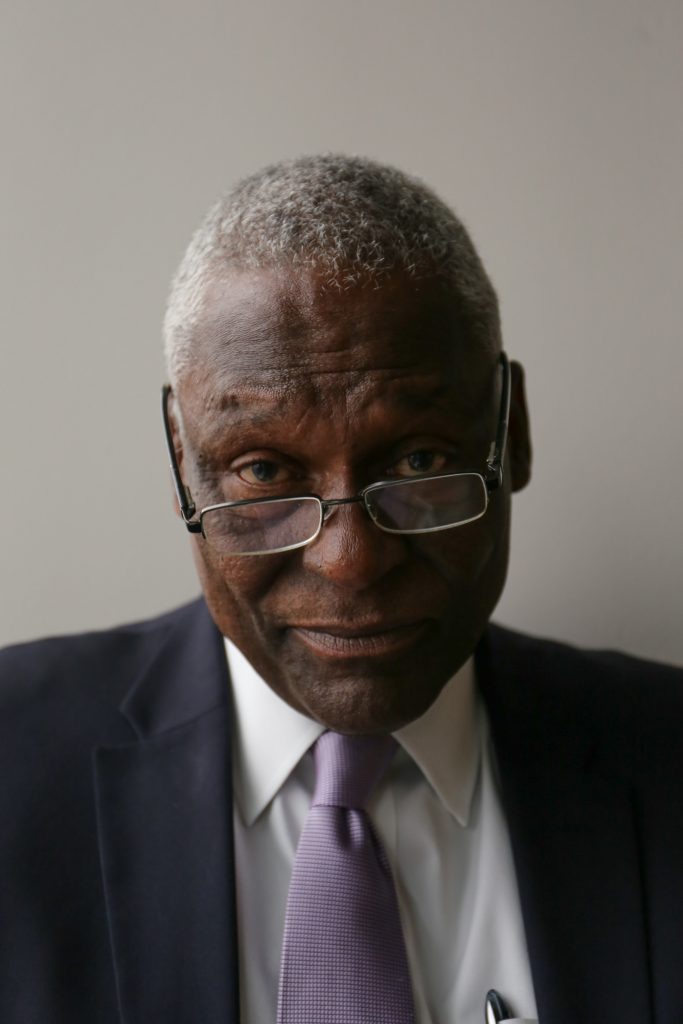

Schneps Media’s Manhattan newspaper group is proud to honor Keith Wright — former state assemblymember and current New York County Democratic Party chairperson — as its Person of the Year.

BY LINCOLN ANDERSON | Updated Thurs., Jan. 17, 10:15 p.m.: Anyone who knows New York City politics knows Keith Wright well. He’s a veteran of politics in both the city and Albany, who remains a force even more than two years after leaving office.

A native son of Harlem, Wright, 64, was first elected to the New York State Assembly in 1992, going on to win re-election 11 times, serving 24 years, before retiring from Albany in 2016.

His tenure in the Assembly saw him champion an array of progressive causes as he chaired various committees over the years, such as Housing, Election Law, Social Services and Labor.

He has fought for the rights of domestic workers, boosted benefits for seniors and gone to bat for public housing residents, among others.

In a wide-ranging interview, Wright recently talked with Schneps Media about growing up in Harlem — where he still lives — his political career, the critically important task of electing good judges…and, oh yeah, that special election in 2017 when Assemblymember Brian Kavanagh got the nod over District Leader Paul Newell to run to fill the state Senate seat formerly held by Daniel Squadron.

Before the Assembly, in what he admits was probably his favorite job ever, Wright was the director of then-Manhattan Borough President David Dinkins’ s Uptown Office. He loved being on the ground in his own neighborhood, engaging with constituents about their concerns and helping them out.

“I got to know and serve my own neighborhood,” he said. “It was a privilege.”

He has a political pedigree of sorts. His father, Bruce Wright, was a lawyer who became a New York State Supreme Court justice. His mother was a principal at a Harlem public school — though Wright himself attended the Ethical Culture School on the Upper West Side and then Fieldston High School in the Bronx, getting an education infused a “humanist” perspective.

“They emphasized public service and helping your fellow humans,” Wright said.

In the spirit of the times, he and other black students took over Fieldston’s administration building for five days in 1970. Their demands were for more black studies and black teachers.

“And we got them,” he said.

But what Wright has also been known for since 2009 is perhaps something a little more arcane for the average New Yorker. During that period, he’s been the chairperson of the New York County Committee, and as such, he’s played a very important role. The County Committee, under Wright’s supervision, is responsible for the Democratic judicial candidates that Manhattan voters see on their ballots when they go to the polls.

Under a process that has been hailed for creating greater diversity and quality on the bench, Manhattan judicial candidates go through a screening process before panels composed of lawyers and members of community groups. The panels then present up to three candidates for each seat that they deem qualified.

“As the chairperson of the New York County Democratic Committee, one of my primary interests is to make sure we have good judges on the bench,” he explained. “Notwithstanding the registration of more voters, our primary function is to have good Democratic judges on the bench and make sure we have good diversity on the bench.”

Wright’s predecessor as county leader, the late Herman “Denny” Farrell, who died last May, started the process.

“Denny Farrell certainly left a useful blueprint on how to proceed,” Wright said. “In Manhattan, certainly we have one of the most diverse benches in the United States.”

On the other hand, New York City’s mayor appoints judges for Criminal Court and Family Court. But the County Committee is the body responsible for the candidates for Civil Court and state Supreme Court that are on the ballot.

“They have to go through a very rigorous screening process” to be “reported out” — as in, recommended, by the panels — Wright explained. As County Committee, he’s in charge or organizing these screening panels.

Although the New York County Committee did endorse Letitia James for state attorney general in her recent victory, Wright said it won’t be endorsing in next month’s free-for-all special election for public advocate.

“You have like 20 candidates,” he said. “I don’t think it makes sense for the County Committee to endorse.”

Although Jumaane Williams and Melissa Mark-Viverito are the likely frontrunners, it’s anyone’s guess who might win, he said.

Asked to handicap the 2020 presidential election and say which Democrats he likes, Wright offered, “Listen, it’s going to be a mad dash — another 20 candidates, like what the Republicans put forward last time when they had 17 candidates.”

He mentioned Senator Kirsten Gillibrand’s name, noting of the New York County Committee, “We were the first county to endorse Gillibrand when she ran for Senate.”

As for who the next mayor of New York City might be, he said not to underestimate City Comptroller Scott Stringer.

“I think Scott Stringer has a big leg up because he’s the only citywide elected official [running] now that Tish is out of it. She would have been a good candidate,” he reflected about A.G. James.

Asked about City Council Speaker Corey Johnson’s chances, he said, “I think Corey’s great. I was a supporter of his from early on. He would be formidable. He drinks and sleeps politics.” On second thought, he added, “I don’t think he sleeps.”

Wright was also co-chairperson of the New York State Democratic Party for two years from 2012 to 2014.

Harlem is a central — and cherished —part of Wright’s identity. He still lives in the same rent-regulated apartment in the Riverton Houses that he grew up in as a kid, at 135th St. and Fifth Ave. When Wright’s father returned from fighting in World War II, the family tried to get into Stuyvesant Town but was rejected.

“They said, ‘No blacks allowed,’” Wright recalled, matter of factly.

“Listen, that’s part of our history,” he shrugged of New York City’s past. “We don’t run away from it.”

The Riverton Houses were built for the black middle class, he noted. It was the same concept as Stuy Town, but it was an era when racism was blatant.

Nevertheless, Wright loved growing up there, and made great friends there, with the likes of Dinkins, Harry Belafonte, Jr., and others.

The Stuy Town rejection wasn’t the first time prejudice would strike his family. His father got into Princeton — with a full scholarship. But when he arrived on campus to check in, he was promptly told he was not welcome, according to Wright.

His mother was politically active and took him to the March on Washington when he was 7.

Wright has been married for 31 years. His wife isn’t political, but works at Studio Museum of Harlem — another connection to the famed neighborhood.

“I tell you, I’m Harlem, brother — stone cold,” he quipped.

At the same time, he can’t help but recognize changes to the area.

“Every neighborhood changes,” he reflected. “I always say, the white folks aren’t coming to Harlem because they like black folks so much. They’re getting priced out of their neighborhoods. There are places up in the South Bronx where I wouldn’t have picked up a stray dog” that are now trendy, he noted.

During his tenure in the Assembly, Wright worked to end vacancy control for rent-regulated apartments and the practice known as “preferential rent.”

“It’s pure bait and switch,” he said of the latter, which lures in tenants at lower rents, then seeks to gouge them later.

“Especially in Manhattan, the price of every condo is $1 million. Where are people supposed to live?” he said.

As for the small business crisis, Wright said, “Something’s got to be done.”

“We tried to put forth something called ‘commercial rent control,'” he said. “But I don’t think it was deemed constitutional. Commercial rents are just out of control right now. That’s why you do see these empty stores.”

Wright now works for Davidoff, Hutcher & Citron as the director of its government relations group.

“For the first time in my life, I’m making a few dollars,” he mused. “I was making $79,500 for 25 years. That’s all I made – put two kids through college.”

As for leaving the Assembly, he quoted Kenny Rogers, “You gotta know when to hold ’em, know when to fold ’em.”

Left unsaid, though also a factor, no doubt, was his loss to Adriano Espaillat in a very close Democratic primary race in June 2016 to succeed retiring longtime Congressmember Charles Rangel. Congressmember had been a natural progression for Wright. But he patiently waited and never challenged Rangel while the Harlem lion remained in office — probably too long, even after he had been censured by his congressional colleagues. Meanwhile, the district’s demographics had changed enough to help Espaillat, who is of Dominican background, to pull out the win.

At Davidoff, Hutcher & Citron, Wright has been repping the group Just Leadership U.S.A., which is working to close down Rikers Island.

“It’s just a cesspool,” he said of Rikers. “I think community jails work better rather than throwing people down the snake pit. I think it’s going to be like [legalizing] marijuana. It’s gonna take time, but it’s going to be closed.”

Although the firm’s Sid Davidoff is a lobbyist, Wright noted he himself is not a registered lobbyist. Which brings us to the epic Kavanagh-Newell showdown of September 2017, after which critics of the outcome angrily slammed the former assemblymember for allegedly being the “L” word.

“It was a mess,” Wright admitted. “I never asked for it.”

But, he said, “due to the way that the law was written,” he and Frank Seddio, the Brooklyn party chairperson, had to pick the Democratic nominee for the special election. This was because of a quirky rule applying to “intraborough” seats — for districts spanning two districts. The state Senate seat stretched from Lower Manhattan to Brooklyn.

Seddio chose not even to let his County Committee members vote, and instead just gave all the votes to Kavanagh. In Manhattan, Wright did let his members vote, and Newell got the lion’s share. But when the Manhattan and Brooklyn votes were combined, Kavanagh came out ahead.

“I went through a process,” Wright maintained, adding that, in Manhattan, at least, the County Committee does get to vote on such matters.

Wright took flak for how it went down, but he’s unapologetic.

“And I haven’t heard from Kavanagh since,” he noted. “He hasn’t called to say, ‘Thank you,’ nothing.”

At another point, he actually called Kavanagh “an ingrate.”

And Wright said he actually really likes Newell.

“Paul Newell’s my guy!” he said. “To be honest — hell yeah! Newell would have been great — no doubt about it. Paul is cool. He’s going to law school and he’s going to be brilliant.”

Tony Hoffmann, a former district leader and president of the Village Independent Democrats, hailed Wright for upholding the rigorous screening process for judicial candidates.

“New York County, Manhattan, has extremely diverse, quality judges,” he said. “And a lot of it, Keith Wright can take credit for. A large number of women and a large number of minorities, and they’re mainly good. It’s a good judiciary. It started under Denny, and Keith continued it. Before Denny, there were a lot of hacks in the judiciary.”

On the Kavanagh-Newell flap, on the other hand, Hoffmann said Wright simply could have said all his County Committee votes were for Newell — essentially overriding the votes for Kavanagh.

“Since Newell got two-thirds in Manhattan, we felt he could have put 100 percent behind Newell,” Hoffmann said of Wright, adding, “The votes of the County Committee are not binding.”

Told of Hoffmann’s comments, Wright responded, “This was all very much uncharted territory. I could have snapped my fingers and said, ‘It’s Paul Newell.’ But we don’t do that in Manhattan. Others do.”

He noted that these intraborough special-election situations “come up every 40 years.”

Village Democratic District Leader Arthur Schwartz is a big fan of Wright — and predicts a return to public office for him.

“Keith is one of the least arrogant and most personable people in politics,” he said. “And compared to other Democratic County leaders, he does not lead with a heavy hand.

“That doesn’t mean that he hasn’t pissed a few people off,” Schwartz added. “But he genuinely wants reformers and party stalwarts to like him.

“When I told him I was working with Bernie in 2016, he said, ‘I would have expected nothing less,’ and then allowed an open countywide debate and straw poll to be scheduled — which Bernie won. I cannot imagine that he will not return to elected office — higher than district leader — one day.”